Transforming education – Government initiatives and collaboration for ICT advancement in India

In a set of thought provoking exchanges, Dr Vijay Borges, Dr Chintan Vaishnav and Shri Himanshu Gupta (IAS), share their experiences of leading governmental initiatives in the STEM/ICT/CS education space.

When it comes to scaling up computer science education in a country as large and diverse as India, government stakeholders have an important role to play in terms of taking a renewed look at policymaking. These include overhauling of syllabus, introducing subjects relevant to the future, launching relevant initiatives to promote and provide computer science and future skills learning with wider access, and meeting the economic and geographical challenges.

We had the opportunity to interview Dr Vijay Borges, Project Director, Project Management Unit, Coding and Robotics Education in Schools Scheme (CARES), Government of Goa; Dr Chintan Vaishnav, Mission Director for Atal Innovation Mission (AIM); and Shri Himanshu Gupta (IAS), Director of Education, Government of NCT of Delhi. These officials have played critical roles in the education landscape broadly, and in computer science and future skills learning specifically. In this piece, we discuss with them the challenges, milestones and the road ahead in making Indian education future ready through computing education.

Maulika Kulkarni: Can you please share some insights into the various initiatives and policies undertaken by the government to promote access and learning in computer science (CS) and technology education?

Dr Vijay Borges: In response to the growing importance of computer science and technology education, we have launched several initiatives and policies to enhance access and learning in these fields. The journey of Coding and Robotics Education in Schools (CARES) Scheme, Goa, started in 2021, a few months after National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was drafted and presented. NEP 2020 is divided into three parts — school education, higher education, and skilling education. NEP 2020 emphasizes three critical aspects: computational thinking, design thinking, and mathematical thinking. Rather than treating subjects such as mathematics, social sciences and art in isolation, it emphasizes the need to view them collectively.

This holistic approach aligns with 21st-century skills, emphasizing collaborative efforts, cross-disciplinary knowledge integration, and horizontal thinking. The goal is to nurture a child’s thinking abilities through innovative and experiential pedagogical approaches.

In January 2021, approximately 6 to 7 months into this journey, the coding and robotics program (CARES) was conceived. This initiative aims to inculcate computational and design thinking into the educational framework. It seeks to encourage diverse thinking approaches when addressing problems. Instead of compartmentalizing subjects, the program shifts towards a holistic approach. This includes considerations like abstraction, algorithms, and the merging of various elements to provide a more comprehensive learning experience. The ethos of the program lies in the pursuit of problem-solving and the development of practical solutions.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: The larger vision is to cultivate a million neoteric innovators — people who will have the capacity to navigate uncharted territories. In hindsight, there are two things. First, there wasn’t a grand epiphany, and second, the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM) was announced in the budge prior to which there was some brainstorming.

The early ideas of launching Atal Tinkering Labs began with a good accidental encounter with a paper that discussed ideas such as “If you were given x amount of money, what would you do with it?” A lot of brainstorming took place before a person suggested giving 3D printers, which is what led to conceptualizing this makers’ space called Atal Tinkering Labs. Over time, it has grown to incorporate design and computational thinking.

When you look at school labs, there have been two waves before the makers’ lab wave, the science labs wave and the computer labs wave, which are very different from each other. The makers’ lab was possibly the first time that both minds and hands are involved. In science labs, they prove what is known, in computer labs, they digitize what is not digital, and in makers’ labs, they create thoughts!

Shri Himanshu Gupta (IAS): The Indian education boards’ curriculum predominantly emphasizes theory and the existing subjects. For instance, after grade 10, if a child wants to study science, they take math, physics, chemistry or biology, and the other options to study are commerce or arts. However, these subjects are not necessarily equipped with 21st-century skills and appropriate assessments. In Delhi, we have undertaken an overhaul to redesign the entire curriculum, which includes subjects like Coding, Robotics, Digital Media and Design. This enables us to introduce coding as a subject which can be taught to grade 11-12 students and assess them as well. In addition to the introduction of these subjects, the Board has also designed assessments that can appropriately test for the skills that are required to master them.

At present, we have a tie-up with Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT Delhi) and I-Hub Foundation for Cobotics (IHFC) to develop a specific curriculum for coding, which will cover important topics like artificial intelligence and machine learning. The syllabus is designed by IIT-Delhi, and assessment is done by the Delhi Board of School Education (DBSE). Similarly, we are bringing new high-end 21st century skills – like film and media making, robotics, automation, automotive courses, fashion and media design courses, and fashion technology courses – to schools. We are also redesigning our courses in partnership with Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and Ashoka University. We have engaged a lot of players to redesign our courses, in tune with the National Education Policy (NEP), which cater to the current needs of the country.

Earlier, other boards encountered a challenge where they had the curriculum but lacked proper assessment methods. However, in Delhi Board of School Education, we have taken the initiative to implement assessments in line with the philosophy of the International Baccalaureate, addressing this issue. This marks a revolutionary shift from the old regime.

Maulika Kulkarni: How does the government plan to scale these initiatives and ensure widespread participation, especially in underserved areas?

Dr Vijay Borges: We are a small state, which is advantageous. I worked closely with our previous Chief Minister, who believed that Goa could be an experiment for the entire country due to its small size and population. Unlike an urban-rural divide, Goa is more like an urban city spread across villages. We primarily focused on 460 government and government-aided schools, not private institutions, all under the State Board. These schools cover various subjects such as science, math, social studies and art. We decided to tackle the issue by working through modifying “computer awareness,” a co-academic subject that already existed and has a familiar sound to it. Since it was not an academic subject, it provided us with flexibility for experimentation.

Our challenge was revamping the entire curriculum, which required aligning with NEP’s 5+3+3+4 structure. We concentrated on the second ‘3’, focusing on middle school (6th, 7th, and 8th grades). In hindsight, was it the right idea? We realized the importance of the first three years, as foundational skills like mathematics and logical thinking are crucial for later development. The Foundational Literacy and Numeracy literature shows that the first 3 are also very important, because if the child has not caught on to the mathematical skill or the logical thinking skill set, then it becomes challenging for them to catch up as time passes.

Another challenge was building teachers’ capacity. While training in-service teachers, we recognized that many lacked a background in science. Therefore, instilling confidence in them was important for the scheme’s success. It may be noted that scepticism often surrounds government initiatives. This leads to a challenge in engaging a multitude of stakeholders. In our case these include, 300+ private management (aided institutes) and 160+ government institutes, 600+ teachers and 65,000 odd students along with their parents. The launch of the scheme in 2021 coincided with the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This presented its unique challenges as this curriculum was envisioned to be hands-on, which now had to be done maintaining social distancing norms.

To gain confidence of the stakeholders, we had to visit and conduct meetings with the managements of 460 schools in all the 12 talukas of the state. The roles of all the stakeholders had to be clarified. Confidence had to be built in delivering the scheme to the end users. We were agnostic whether it was a rural or an urban area. Our approach was practical and worked on continuous feedback from the stakeholders. This helped us meet the expectations of all the stakeholders. This has been a major success over the last three years, since the launch of the scheme.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: I think this program remained open from the get-go, so there weren’t any restrictions on the schools to apply. It could be a private school or an urban school. There needed to be certain criteria: space availability, which grades, whether there is a science teacher, and things like that. But otherwise, it was open to all. Over time, as the numbers grew, there has been a nudge to stratify sampling so that they are somewhat representative of what the landscape looks like. Now 60% of the labs are in rural areas and 70% of them are in government schools. The next milestone for us that we have proposed is 70,000 or 1 in 3 schools. There is also some calculation behind it. If you see the proximity of schools, then one in three is still within the same block. So that was the thinking. It took us five years to build 10,000. So we can’t imagine that to be the model for fulfilling our aspirations in the next five years. Because sequentially we will only be reaching another 10, but we have to parallelly build. So, our proposal is that we build through states and the private sector.

Shri. Himanshu Gupta (IAS): We want to go a bit slow and steady in this. The curriculum we have designed is being implemented in 40 of our government schools. Currently the curriculum is being vetted by industry experts. Once the process is over, we will look into expanding it to all our schools. We will open it for private schools also, who wish to come to our Board to apply for it and take the courses. We are also exploring partnerships with universities such as the prestigious Delhi University to ensure that the students don’t face any difficulties in the application process.

The impact on these schools is visible. We recently organized the Delhi Robotics League (DRL). DRL is a statewide robotics competition for school students. The competition was open for all the schools of Delhi, whether private or government. It is noteworthy that bootcamps with the help of IIT Delhi were organized in schools across Delhi. In the top 16 teams, nine teams were from government schools, and seven were from private schools. The winning team was from one of our Specialized Schools. And they defeated some well renowned private schools of Delhi like Springdales School and DPS RK Puram. So, you can see the prowess of the students. What they have been able to achieve is inspiring.

Maulika Kulkarni: With multiple government pathways and approaches to CS education, how do you ensure a cohesive, standardized and adaptable Pi Jam Foundation frameworks for learning?

Dr Vijay Borges: When you conduct experiments, there’s always a need for someone to lead and provide insightful thinking. However, if you fail to create secondary leadership and a replicable or scalable model, it becomes a failure. As I reflect on my third year at PMU CARES, I must envision a scenario where I, Vijay Borges, do not exist; “Will this model reach an acceptable level of efficiency autonomously?” That’s what we have been striving for. It’s not just about having the right team or leader. It’s about ensuring the model’s replicability and scalability.

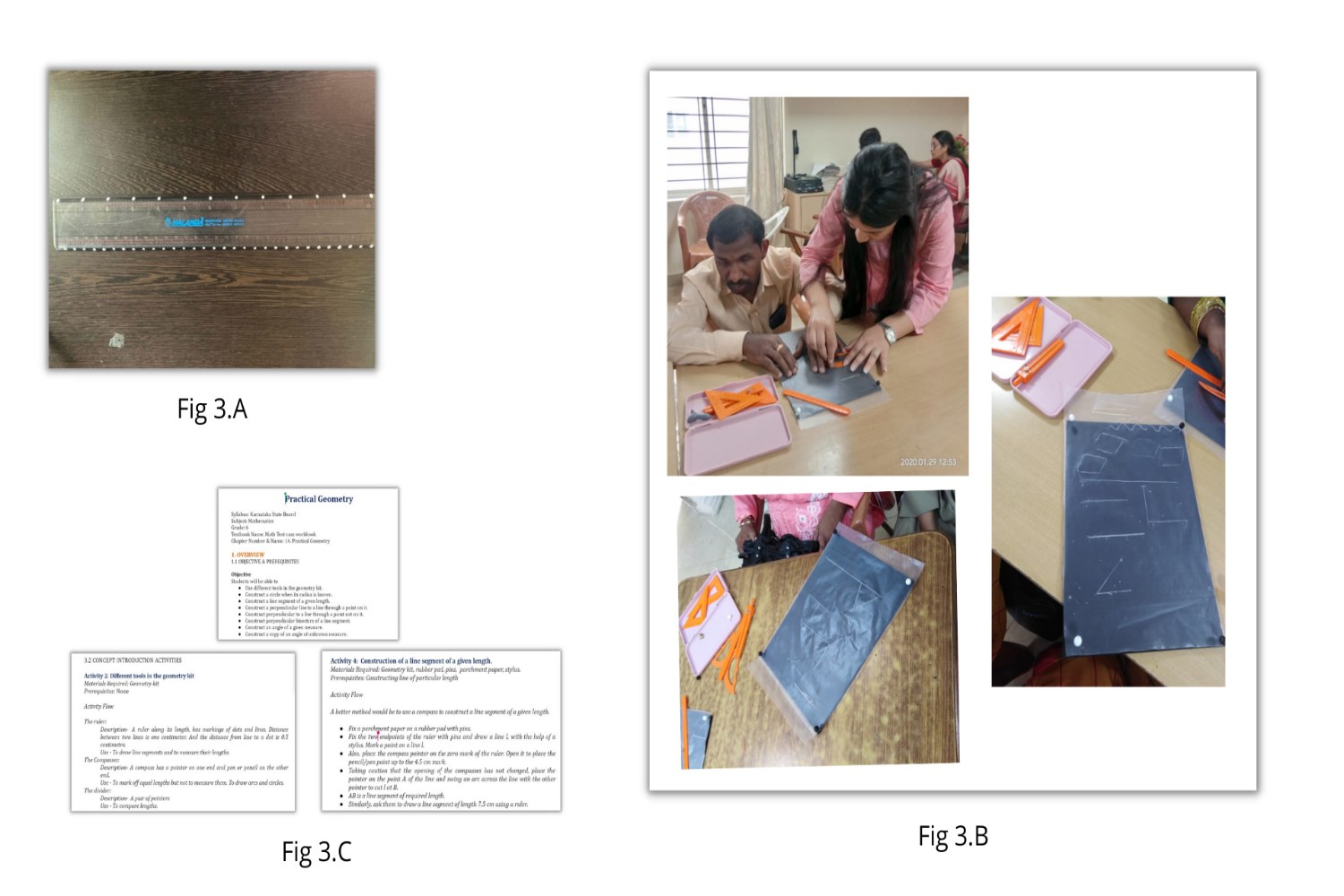

At PMU, I have created R&D teams: one is Educational, and the other one is Engineering. When you are talking about robotics, hands-on experiences, and maker spaces, what is required is a model and an understanding of appropriate teaching and learning materials that are adaptive to hardware and software tools. Many commercial entities may have their promotional interests. So, to drive the government’s interests, the need is to minus the commercial interest and keep the primary stakeholders’ (students’) interest as the highest priority. This can be done only by developing the tools ourselves. So, when PMU signs the MoU, with other entities, the emphasis is to develop the IP together. When we speak to system integrators, we insist on developing the firmware together. By doing this, PMU develops in-house expertise and becomes efficient in being adaptable to create a teaching learning framework that works efficiently with the hardware and software tools.

For experiential learning, the need is to be clear about what is going to be taught, the tools required and how the tools would be adapted five years down the line. Can these resources be reused? Can they be efficiently used? We engage with industry partners on these terms as envisioned by the PMU.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: Initially, three factors led to a slightly larger concentration of schools in some regions. Of India’s secondary and higher secondary schools, 4.4% have an ATL. In some regions, that number may be 5.5%. These variations exist because, first, the schools that were closer to Delhi, and second, regions where awareness and focus on education are higher, such as southern areas, obtained more schools because they actively applied for them, sometimes using third-party agencies to submit applications, which introduced some bias since allocations was based on applications. Lastly, in the frontier regions like J&K, there were fewer initial applications. However, apart from these factors, there was no predetermined ratio imposed.

Shri Himanshu Gupta (IAS): We have partnered with the Australian Council of Education Research (ACER), which serves our Project Management Unit (PMU) assisting in the design and development of assessments. In addition, various curriculum design partners have provided their expertise. An innovative aspect of our approach has been the involvement of our own teachers in devising assessment strategies. This collaborative approach has resulted in the development of a co-assessment framework, fostering stakeholder involvement and garnering positive feedback on our student assessments. We conduct weekly and fortnightly assessments, giving substantial weight to internal assessments within a semester based system, aligning with the draft National Curriculum Framework’s recommendations.

Maulika Kulkarni: What are some innovative government programs related to CS education that have yielded positive results? Could you highlight a few success stories?

Dr. Vijay Borges: To run the elective curriculum – which is a post-school hours activity – on advanced technology for selected motivated students, we offered the Teach for Goa Fellowship. Around 50 graduate/postgraduate engineers and MCAs join us for 2-3 years to engage in school education, primarily to assist us in delivering the curriculum. This curriculum is highly specialized, focusing specifically on mathematics, science and technology. We harness the existing talent pool from the local engineering institutes, providing them with training to supplement school education.

Our Teach for Goa fellows go to various schools for these post-school hour sessions. We implemented a concept called the “Hub and Spoke” model. Across the 12 talukas, we assigned one school as the “hub” or lead school, while the seven schools serve as “spoke” schools. How does this work? The students from the spoke schools along with hub school students convene for a weekly two-hour session. In each session, there are a maximum of 20 students.

A system is allocated to a pair of students. In each hub school two sessions are conducted every day, with a total of 12 sessions in a week. We have 115 hub schools catering to over 8,000 students. We observed that students who came from underprivileged backgrounds worked together with students of privileged backgrounds, giving them a sense of, “Yeh mujh se bi hota hai” (“Even I can do this”/ “Now I know how to do things I had never done before”). It was truly remarkable to witness this change in confidence fostered through the peer learning mechanism.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: In Atal Innovation Mission (AIM), quantitatively, we think the return on every rupee invested is about five and a half rupees as a whole. If you compute the social cost of capital, then it may be about 17 rupees for a single rupee invested. The way we computed this, which is getting published, is a two-part story. One part is incubators, where there are ideas. The incubators have the idea. So, we have invested a total of 325 crores directly into startups, plus some amount on incubators. These startups have raised about 1,350 crores in the market. They have diluted 20% of their stakes on average. This means that these startups have a valuation of about 6,700 crores. That is one form of return. These incubators have raised about 60 crores in matching funds. That is infrastructure valuation.

Through that ATLs, we have sensitized around 75 lakh students. We have computed that had such a person sought a similar level of sensitization privately, they would have spent 1,000 rupees, very conservatively. So that is about 750 crores. So, we come to 8,500-8,700 crores. We have spent 1,511 crores by last year on Atal Innovation Mission. We have had a return of 8,700 crores. So that is five times. It is interesting that the incubators have high returns but less volume, right? These 3,000 startups employ 14,500 people. They pay them maybe 30,000 rupees a month on average, so that is about 450 crores. So ATL’s returns are small, but the impact is larger. That is just quantitative.

Maulika Kulkarni: How does the National Education Policy (NEP) support and enhance computer science and STEM education in the country? Please highlight any challenges or opportunities you foresee.

Dr Vijay Borges: This question is both important and interesting! We are impacting 65,000 students and not everyone is interested in coding. There could be some students interested in advanced technological knowledge. There are different kinds of learning styles. There is some innateness and then there is some that is acquired.

We develop our own tools — both, the software and the hardware tools. For a small state like us, we need to specialize in nurturing human resources. That’s what we did. We came up with something called an elective curriculum. The elective curriculum is where we talk about STEM (science, technology, engineering and math). Here we prioritize higher order of thinking, based on computational thinking, design thinking and mathematical thinking. This has also been emphasized in NEP 2020.

We need to build a symbiotic relationship with talent. Otherwise, the talent will go outside Goa. This is a concern we need to address for the future, looking ahead about ten years from now. Higher education often encounters a problem when a child reaches the age of 20 and it is realized that the talent is not good or not at the desired level. By that time, it’s challenging to make significant improvements to the human resource to be adaptive to the required talent pool.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: We are getting requests for ATLs from far off places. So clearly awareness is growing. Now we do hear from some places where people have complained or demanded in their school, “I have never been given the opportunity to be an ATL teacher.” That is an interesting demand! So, I think it is growing. Maybe that is an indication of being mainstream. It must come from the people, right? Otherwise, everyone is very good at making large claims.

Himanshu Gupta (IAS): I think we are in perfect alignment with what NEP 2020 says. NEP talks about activity-based learning, having career opportunities in line with the skills that are right now required in the industry. This is what we are doing. We are providing them with those skills. Then, our assessments are not like a normal Board’s assessment, where you mug up theory and then you just write it in the exam. We are having a mix of both.

Suppose a child takes music as a core subject. Then 70% of her assessment will be through practical, and she will be performing, and there will be an external assessor who will be assessing. They will be given an opportunity to choose which instrument they want to play and which genre they want, whether it is Hindustani Classical, or Western. Accordingly, their assessment will be done. In different subjects, we have kept that component, and we are giving them grades. We have introduced a credit system. This is what NEP talks about. So, we are giving them credits and a grade system. That way, we are totally in line with NEP 2020.

Maulika Kulkarni: In your opinion, what role does collaboration between the government, the private sector, and educational institutions such as schools play in advancing CS education in the country?

Dr Vijay Borges: Despite the worldwide chip shortage, conflicts and challenges starting in 2021, we have successfully upgraded computer laboratories in all 460 schools, providing over 4,600 systems with all the necessary tools. This achievement represents a win; the people witnessed what a committed government can achieve. Merely setting up systems in the lab without any means of communication, such as internet connectivity, is set for failure. To address this, we adopted an innovative scheme called “Wired Internet in Schools.” The government providing a single vendor to provide internet services could present a single point of failure. To overcome this, we proposed involving around 100 vendors to provide internet services through a rental model. This empowers institutions in an almost revolutionary manner. It allowed them to choose the best services. This also promoted trust and collaboration among stakeholders.

Initiatives like these are collaborative, win-win for all, and come with an inherent distributed functionality; thus, boosting any kind of learning permeability. Another feature of this scheme is the provision of engaging with Teach for Goa Volunteers and Mentors. These volunteers and mentors are industry experts who have been associating with the scheme to provide their expertise in various domains to take these initiatives forward.

Dr Chintan Vaishnav: It would have to be state-led. It may remain a central sector, like it is right now. The answer is not there yet. What is clear is that you cannot do it from the centre, because the numbers are large. And ultimately, schools are answerable to the machinery at the state level. We try to link it to the states even as a part of their teacher training programs. We have said that there will be involvement by the states even in selection. We have allowed schools to apply as clusters and let the states shortlist them first. They are involved in every step, so that would ultimately be the model here.

Shri Himanshu Gupta (IAS): Boston Consulting Group (BCG) was given the main aim of identifying good partners in different fields for our PMU. And on the DBSE front, we had the Australian Council of Education Research. So, BCG played a very important role in identifying the correct people. Then we reached out to them and then centrally managed all the things. And then we have a good team in DBSE, headed by the CEO, Mr. K. S. Upadhyay. We have built a team that is passionate and dedicated towards changing the landscape of education in this country.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!