Enabling multilingual education in schools

Hemangi Joshi and Rajashri Tikhe draw upon their experiences of working in multilingual education in Maharashtra.

This article reviews the approach of Multilingual Education (MLE) recommended in NEP 2020 and provides some insights for its practical implementation in classrooms. The authors work on MLE in Maharashtra. The examples and the insights provided in the article are rooted in the experience of their ground level work.

It is often the case that children from different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds first encounter groups outside their own community and are exposed to the national/ regional language through formal education. Therefore, education is among the most crucial sites for language planning. Schools represent the primary associated institution through which legitimation for state’s dominant language(s) is sought.

Language policy has long been viewed as a powerful instrument for the promotion of an imagined, and sometimes of a desired, sense of identity. It will be apt to review National Education Policy from this point of view.

In India, until recently, policy planners and implementers in departments of education have chosen either a null approach (ignoring the need for framing policies to ensure access to linguistic minorities) or a promotion approach (explicitly promoting a favoured language or languages). At the ground level, these practically result in restricting children in speaking their mother tongue/home language even during informal interactions in school premises.

With this backdrop, it is worth appreciating that NEP 2020 has strongly recommended multilingual education with acknowledgment of the importance of home language or mother tongue in the process of learning at the elementary level. Promotion of bilingual approach and the use of bilingual material by teachers in classrooms are welcome steps.

Very importantly, NEP 2020 has clarified that the language need not to be a language of instruction to master it. It recommends high quality teaching of all languages to be taught to children. Guidelines about the standardization of Indian Sign Language also indicates that the policy not only takes cognizance, but also intends to take concrete steps on the issues of children with special needs.

However, with due acknowledgement of NEP 2020’s strengths with reference to language teaching, it is necessary to discuss the scope for improvement in the approach. This would help us materialize the vision of multilingual approach truly. A hotchpotch approach could be sensed in the section on multilingualism in the policy. While acknowledging the diversity of languages on one hand, it recommends to invest in a large number of teachers only in the languages mentioned in the 8th Schedule of the Indian Constitution, consequently leading to hundreds of home languages or mother tongues being ignored.

It is critically essential that National Education Policy takes a firm and clear stand regarding its final objective of multilingual policy and accordingly its approach towards multilingualism. Does the policy aim at inclusion? That entails seeing multilingual and multicultural education as an end in itself, for which differences between languages, cultures and religions are seen as highly relevant. Alternatively, does it aim to be exclusionist, in which differences are denied and assimilation is the primary goal?

The expressions of chauvinism in initiatives like ‘Ek Bharat, Shreshtha Bharat’ endorse the observation that the ultimate objective of policymakers is accommodation or assimilation of language minority groups into dominant/preferred language of those in power. Policymakers seem to be strictly emphasizing the commonalities in phonetics, scripts and grammatical structures in ‘India’s Most of the Major Languages’ and claiming their origin in Sanskrit language.

It is worth noting that the policy omits the mention of acknowledging and appreciating the differences and uniqueness of many more Indian languages. It would have been apt for the policy makers to consider the fact that Indian languages are categorized into four main language families; namely, Indo-Aryan Languages, Dravidian Languages (which are in fact older than those of the Indo-Aryan family), Austric Languages (Austro-Asiatic sub-family) and Sino-Tibetan Languages. Except for some Indo-Aryan languages, those from other three groups hardly have common phonetics, scripts or grammatical structures. They do not originate or source their vocabulary from Sanskrit as well.

Policy makers are mainly referring to north Indian languages, specifically those from the Indo-Aryan family, while discussing multilingualism. They seem to be making further claims of Indian languages being the richest, most scientific, most beautiful, and most expressive in the world, with a huge body of ancient and modern literature.

This again creates doubts about the clarity of policymakers regarding the understanding of the core values of multilingualism and multiculturalism. The approach of celebrating diversity has an inbuilt sense of respect for other languages and cultures. It would have been principally correct to mention Indian languages as different in their richness, beauty and expressiveness, rather than claiming them higher in quality than other languages in the world.

Lastly, absence of a firm stand on the ultimate objective and approach of multilingual policy is reflected in the recommendation of bilingual books with English as a second language. The option of home language/mother tongue and regional language for bilingual books should have been considered, especially for children learning in vernacular medium schools. In order to achieve multilingual education in practice, we would like to suggest the following proven strategies and policy changes.

Multilingualism and the medium of instruction at primary grades

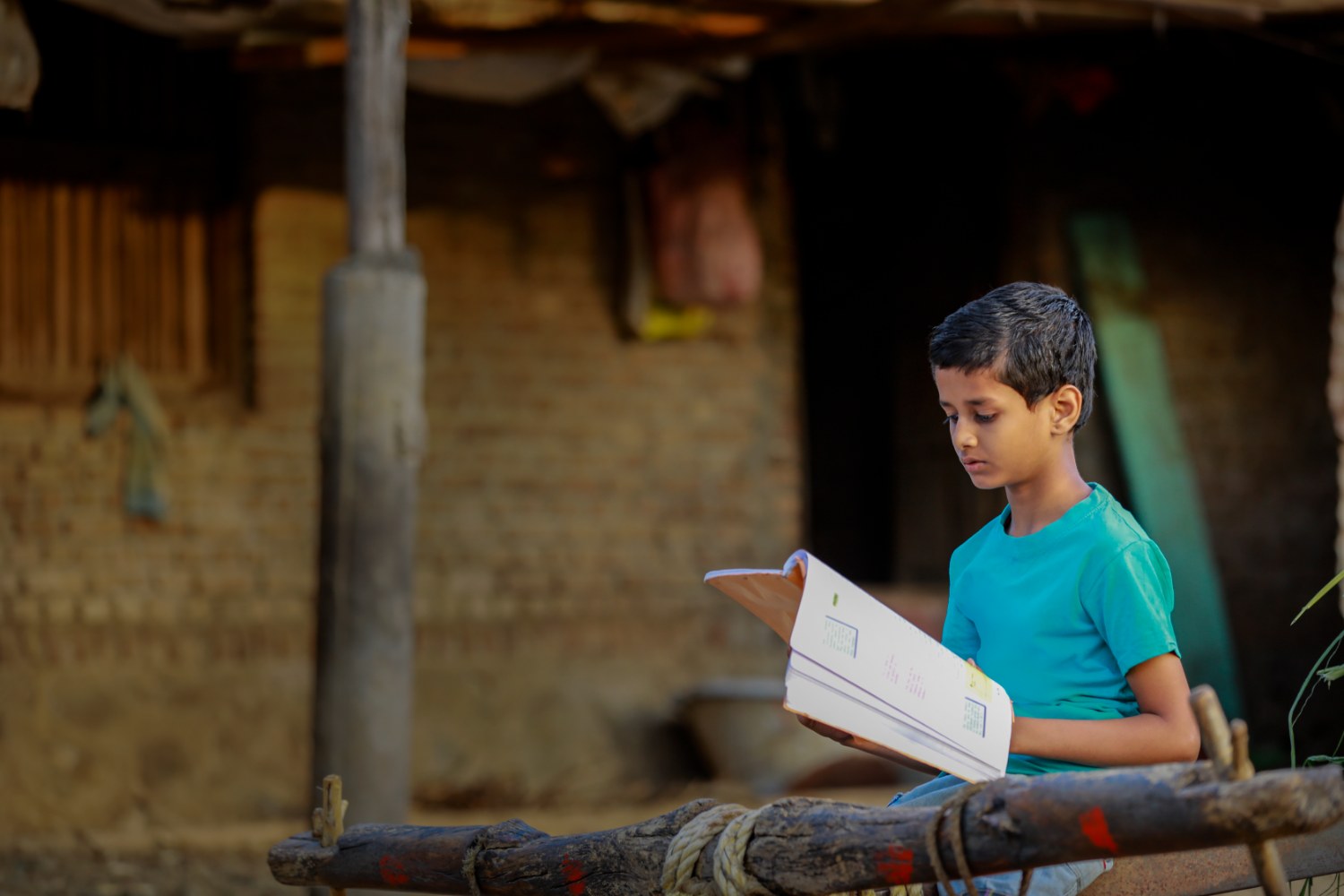

In fact, any Indian school is naturally multilingual or at least bilingual. The language in the surroundings of a child is usually a regional language, which many a times is different from her home language. Teachers come to the school with some other language(s), often their own and the state’s official language(s).

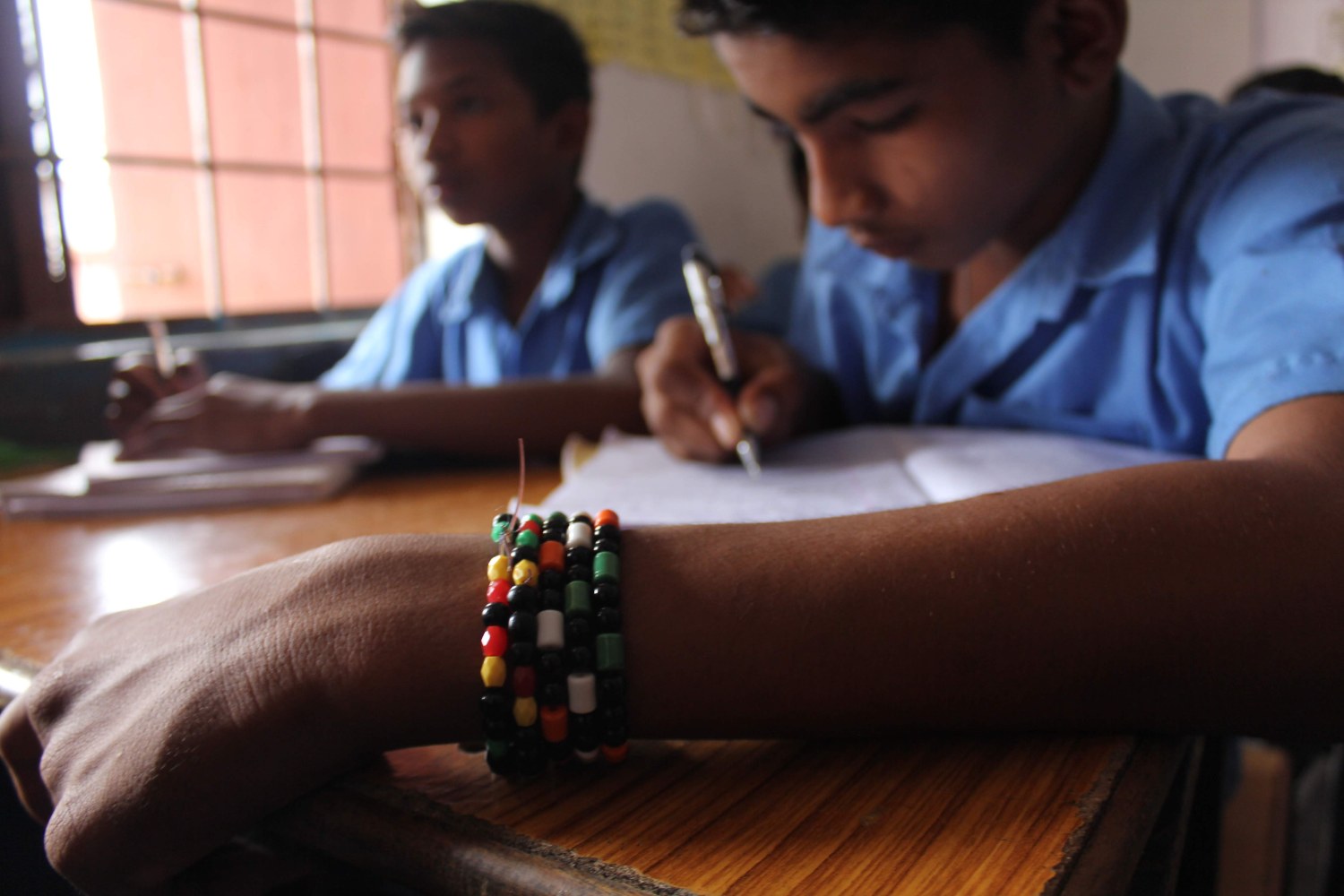

However, classroom processes becomes inorganic and un-educational, when the system pressurizes the use of only one language as the medium of instruction and education. From our practice, we want to argue here that it is very much possible that the medium of instruction and education at the primary grades comprises of 2 to 3 languages. E.g., we, at Unnati ISEC use Korku (children’s home language), Hindi (language of surrounding) and Marathi (State’s official language) for the purpose of education and developing literacy skills.

Since Korku doesn’t have its own script, we use Devnagari script for Korku which is common for Marathi and Hindi. The choice of using a script for a non-scripted language has to be made thoughtfully, which requires policy attention. In mega cities with considerable rates of migration even from other states, the option of a common communication language could be considered. Even literacy skills could be taught using different languages.

There is a strong need to revisit the present rigid mindset of the government and of the people. This poses a major challenge in breaking the pattern of single language instruction and making education accessible to diverse communities in a true sense.

Revisit the policy of the language of the textbooks

Presently Government of Maharashtra has developed bilingual textbooks in Marathi and English. Non-cognizance of the home language or mother tongue is apparently seen on the part of the government. We are afraid that such a move, will add a burden on the teachers, children and the whole educational process. Here, the option of home language/ mother tongue along with the regional language for bilingual books should have been considered. This would have been more aligned with sound educational principles.

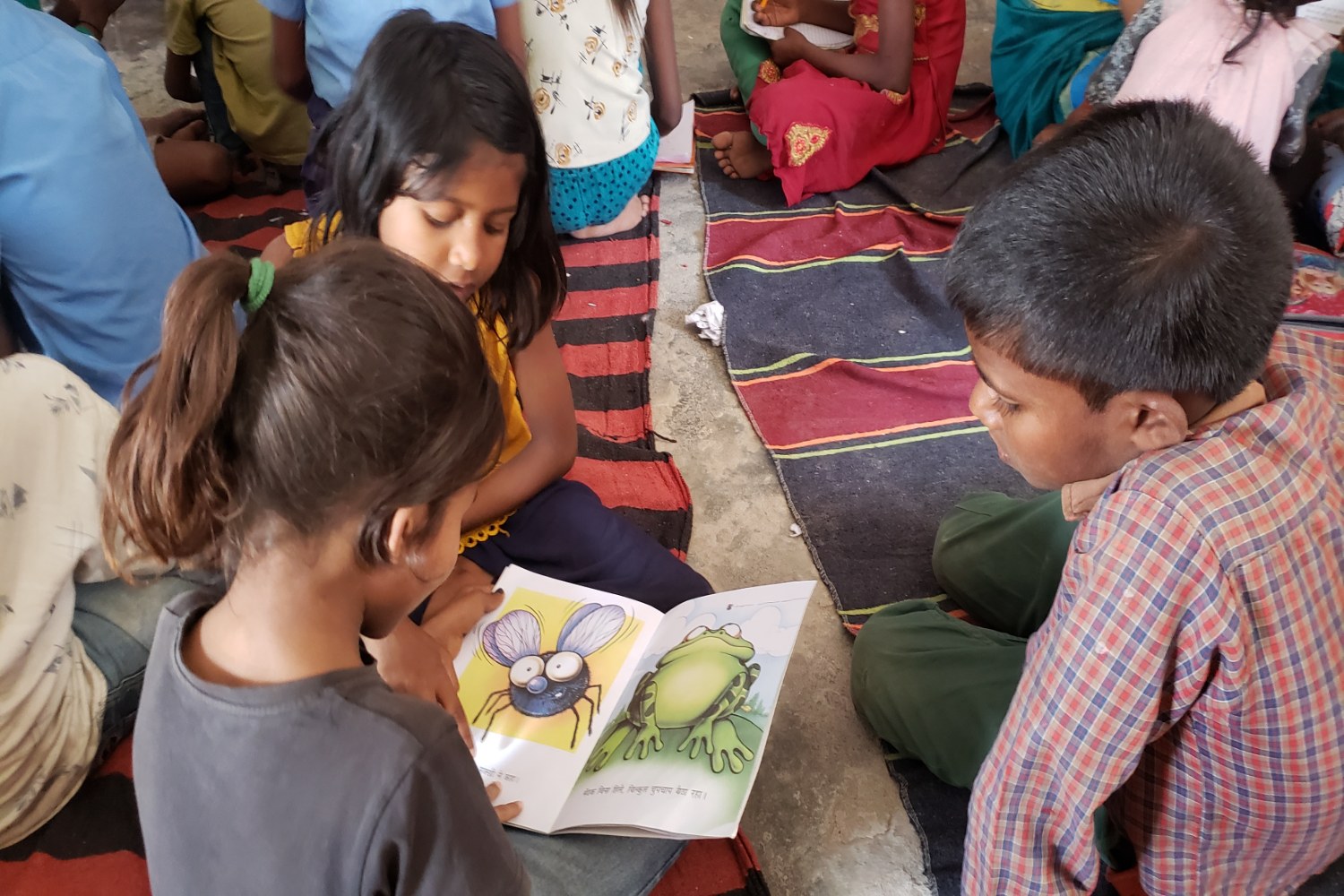

Governments of Chhattisgarh and Odisha, and NGOs like Patang India and Unnati ISEC are some examples in the country, which have done this and seen good results educationally. A. Jakhade mentions in ‘Bharatiya Bhashanche Loksarvekshan’ (Padmagandha Prakashan, 2013) that 56 language-communities reside in Maharashtra. We need to revisit the policy of the language of the textbooks in states like Maharashtra, which have large numbers of linguistic minorities, to facilitate educational inclusion in a true sense.

Teachers learning children’s languages: government’s responsibility

Teachers are the key factor in achieving multilingual practice in classrooms. Even NEP 2020 has stated that it is non-negotiable that the teachers know children’s languages. It is advisable to recruit teachers from the local communities sharing similar linguistic and cultural backgrounds. However, it may not always be possible at times for the reason of non-availability of such teachers.

In this case, it becomes imperative for the government that it arranges for crash courses for teaching mother tongue/home language of the concerned students for these teachers. Such language training courses may include orientation to local cultures as well, to facilitate the inclusion of the context of the child’s life holistically.

In Maharashtra, Tribal Research and Training Institute, Pune, has created a course book on teaching Gondi, Bhilori and Pawari languages. Unnati ISEC, an NGO, has created a course of teaching Korku language to teachers and the public.

Governments need inputs on implementing MLE

NEP 2020 expects the use of home language/ mother tongue not restricted only as a language of instruction. It expects its teaching as an independent language as well. While the Maharashtra state government recognizes the importance of MLE in school education, there is a big confusion over its implementation at the school level. These aspects include classroom teaching and learning, language of the text material and the evaluation strategy. We are sure that such confusion exists in many other states as well.

Government of Maharashtra encourages the use of children’s languages in the classroom. However, it does not provide clear guidelines on how and to what extent children’s languages are to be used and what pedagogy should be adopted.

The evaluation system concentrates only on the acquisition of literacy skills in the state’s official languages and that too within a stipulated time period. It is practically difficult to achieve this in areas where children’s own language is different from the state’s official language(s).

This fact is ignored, and the sole responsibility of identifying the ways of using children’s languages and achieving the results, at the same time, is passed on to the teachers.

In fact, only a few teachers believe in the multilingual approach and work proactively towards it by creating supporting material. However, not only their efforts and approach goes unattended and unrecorded, they are also discouraged at times by the system. They are often expected to perform according to the state’s expectations of children’s achievement.

The state government has no clear position and guiding document over MLE in schools. Similarly, development of support material for teachers, such as glossaries in home language or mother tongues, repositories of bilingual stories, songs and a variety of books in different genres, and audio material is equally important to make teachers familiar with the accent of the home language and mother tongue of students.

Need for multilingualism policy in school education at the state level

NEP 2020 is a guiding policy document for the country. However, the arguments made above for making MLE a reality and the challenges mentioned, indicate towards the need for formulation of state level policies on MLE. States will have to consider the diverse and differential cultural, political and educational ethos of their regions and would need to come up with implementable policies and plans of action for MLE.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!