In Conversation with BlueJackal

In this interviews with groups working around issues of children’s literature and equity, we bring before you challenges in producing and sharing books and narratives that speak to the diverse childhoods in the country.

BlueJackal is an independent platform for engaging with, creating and publishing visual narratives, comics and picture books. It also initiates dialogue and learning within these contexts through interactive programs. It is run by Shivangi Singh, Shefalee Jain, Lokesh Khodke and Sharvari Deshpande. Shivangi and Lokesh participated in the conversation. While the interview was conducted bilingually in English and Hindi, the transcript has been translated to English.

Surya (Prayog): How did the thought to start this publishing house emerge? Why did you feel the need to start something new? Also, the name is very intriguing. How did it come up?

Shivangi (Blue Jackal): The beginning of BlueJackal was from a meeting with friends. We were all informally discussing our desire to move beyond individual art practices, studios and art galleries. In such spaces an artwork often just ends up getting displayed on walls. A very limited audience becomes the viewer. The first such meeting happened at Lokesh’s and Shefalee’s house in Delhi, sometime in 2015.

Then, all of us were working in our respective jobs as well as practising art. However, we wanted a space where we could collectively think and create something. Many of us who met then, had some experience of working as children’s books illustrators. Publishing as a collective activity and engagement became one possible centre of interest.

This we thought would allow us to move beyond our studio practices, push us to think about the kind of stories we wanted to tell and also the kind of audience we wanted to reach. This was the beginning of what would eventually become BlueJackal.

We started off with ‘Situation Comics,’ which is an open call for participants to respond to a given situation/prompt, in the form of one-page comics. We propose a situation or a prompt based on a historical event or on a fabulation, which invites creative participation to unfold as a comic strip. Situation Comics has had three episodes, each of the open calls received a wide range of entries that also addressed the contexts of the artists who made them.

Our first ‘Howl for Entries’ (a play on ‘Call for Entries’) came from a need to reflect on Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder and the poignant and strong last note that he left for all of us to grapple with. Rohith Vemula, a Dalit PhD scholar from University of Hyderabad, Telangana, India, wrote this note just before he was pushed to take his own life on January 17, 2016, due to caste-based discrimination within the university.

We received entries from a variety of artists. Their responses and concerns were diverse. What we loved was that people who were not formally trained in the Visual Arts also participated in this! It was so exciting to be able to build a platform where contributors can share their artworks while retaining complete ownership of it. One of the reasons to start the platform online was to go beyond the exhibition spaces we were familiar with. Another cause was that it was possible with limited funding.

Lokesh (BJ): Like Shivangi said, we were already connected to the world of books through publication houses like Eklavya Publication, Muskaan Publication, and with magazines like Chakmak (published by Eklavya, Bhopal). We had been conducting workshops with children as art educators as well. And these experiences pushed us to ask certain pressing questions like, ‘What is childhood?’ Can it be defined? If yes, then what are the multiple ways in which this could be done?

We wanted to take these questions forward at BlueJackal. Therefore, our platform began evolving organically as well as consciously. Initially we were unclear about what our source of funding would be. However, we did not stall work due to monetary constraints. We were aware of, and influenced by, zine culture and little magazine culture, as well as the graphic novel and comic culture of Delhi. So, this encouraged us to publish with limited means on cheap paper at affordable prices.

We wanted the name of our group/initiative to be something playful and yet thought provoking. We were discussing several names when the story of ‘Ranga Siyaar’ came up. The siyaar/jackal in this story is seen as a ‘treacherous’ and ‘shrewd’ animal, who ‘deceives’ the other animals with his accidently found blue coat. But looked at from another point of view, it is also a story of survival of the jackal in the treacherous and hierarchical forest.

The story also reminded us of casteist proverbs like “isne apni jaat dikha di” or “asli rang dikha diya.” These imply that, one must not cross boundaries of given identities. And that if one does, then they will be shown their ‘true’ place. We wanted to keep with the idea of playful treachery, which for us is not manipulative but an adaptive means of survival.

Surya (P): So wonderful! This brings me to a question. Some books portray risky texts. Not risky because it should be kept away from readers, in fact all the more reason to read it. However, because it holds some complexity and hence is significant. We have to also think whether our readers are prepared to be opened up to these topics. So how do you choose these topics? What are the challenges associated with these choices?

Lokesh (BJ): I suppose your question comes from the context of children’s literature and what is appropriate or accessible to children. BlueJackal is not a children’s book publication. But at the same time, we also don’t want to keep children from reading our books. We have always wanted to break the boundaries between children’s literature and the so-called adult literature. It is quite a challenging task, but also worth working toward.

Children come from diverse experiences and backgrounds. These give them different kinds and intensities of experiences and knowledge at various points of their childhood. It is unfair, when we decide to open content to them just on the basis of certain normative standards. These often come from people like us, who are mostly from a very limited upper middle class understanding of childhood. So, it is tricky to decide which themes should be opened to the children just by looking at their age.

Let’s take the book ‘Payal Kho Gayi’ (Hindi), which has been published by Muskaan and Eklavya, as an example. It has been written by children from a basti and illustrated by Kanak Shashi. It was produced as part of a workshop conducted by Muskaan. Here, six to eight year olds from a small basti were asked to respond to a hypothetical situation. They were requested to imagine that their friend Payal had gone missing. Could they guess where she could be? Where would they look for her?

The children thought over this and also made some drawings. ‘Payal Kho Gayi’ was born out of these very thoughts and drawings of the children. Among the many possibilities that the children thought of, regarding where Payal could be, two can be seen on the inner side of the front and back covers of the book in the form of drawings. One shows Payal could be in prison and another shows a man abducting Payal in a car.

Now, many parents and teachers might argue that young children should not read this picture book. However, we must remember that there are many kinds of childhoods around us. Children from diverse backgrounds are exposed to multiple kinds of realities. Therefore, it becomes important to address these. How we could do this remains an important question to address. You can read an article on ‘Payal Kho Gayi’ by Shefalee Jain on the BlueJackal website.

Shivangi (BJ): In BlueJackal’s latest set of books ‘OCTA 2021: Two One Za Two, Two Two Za…’ our effort was precisely this. We wanted to, together with other artists, think about the category of childhood through workshops. Childhood is very often viewed as ‘good’, ‘innocent’ and in need of ‘protection.’

These stereotypes extend to children’s book illustrations, where an ‘ideal child’ is often illustrated as – the fair skinned child, the obedient child, the gender conforming child.

To rethink these ways in which we define childhood, we invited 24 artists for these workshops. We gave them a prompt to help begin the process of this rethinking. The prompt was to bring one or more rhymes and proverbs from their growing up years, in their mother tongues. These were to be used as tools to critically rethink images and imaginations of childhood.

The discussions around these rhymes and proverbs opened a diverse picture of childhood for each of us during the workshops. ‘OCTA 2021: Two One Za Two, Two Two Za…’ brings together these reflections in the form of illustrated picture books, stories and rhymes. It compiles seven books of different sizes and formats into a book box.

Binit (P): We got a chance to read many of BlueJackal’s latest books such as ‘Chudail’ and ‘Dohri Zindagi.’ These books touch upon various topics and themes which are so present in our daily lives and experiences. However, not everyone talks about them. I would like to know what inspires your choices of themes and topics while making books?

Lokesh (BJ): Thank You Binit, for sharing so elaborately on how you are reading, and also looking deeply into the books. It is very encouraging to hear this. It makes us want to continue to work in this area. Actually, what you mentioned about layers of life is itself our inspiration behind creating them. If life is filled with so many layers, why keep touching just one repeatedly? Doing so creates a kind of opaqueness, where we fail to see the diverse layers of our own, and of other’s, lives.

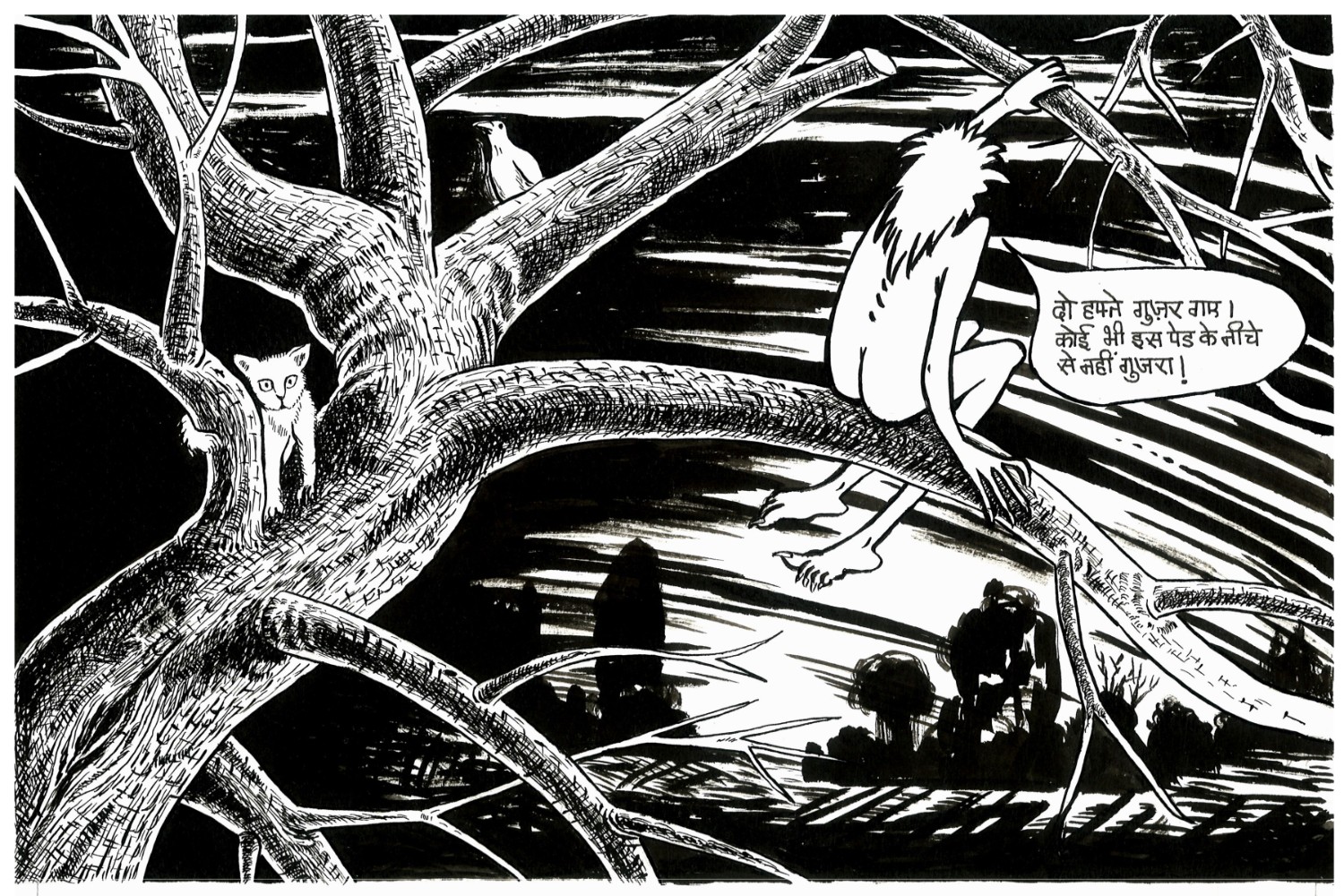

For example, while making ‘Chudail,’ I had thought that it must be a comic which is humorous. It must bring in a critical reflection on politics, culture, family and gender, in a way that these feel like a part of our daily lives. How can I try to put forth pertinent and thought-provoking questions to the readers, without generalizing them and yet not making them very remote and difficult to grasp.

Shivangi (BJ): Also, what is happening around us in post-2014 India is important. We want to reflect upon that. We want to do this through comics, stories and graphic narratives. It is not always necessary that the current state of things be expressed through journalism. It can be commented upon beautifully and effectively through stories too. And, journalism is not what it used to be earlier. So, we make visual stories that are playful and poetic and are at the same time rooted in socio-political realities. Some examples of this are ‘Letters to O’ written by Lokesh, ‘Ek Philistini Shayad Kahe’ by Shefalee Jain and ‘Laila Majnun’ by Sharvari Deshpande.

Lokesh (BJ): Similarly, ‘Dohri Zindagi’ is a folktale from Rajasthan, retold by Vijaydan Detha and illustrated by Shefalee Jain. This story has been adapted earlier through plays. So, when Shefalee chose to work on it, she wanted to focus on the other, lesser visited layers of the tale through her illustrations.

Words build a story. As artists, we also bring a parallel reality to these words. This reality comes from our experiences. Sometimes these also come from the different times and geographies that we belong to.

So, when the two come together, the narrative need not always essentially portray just what the words are saying. Illustrations have their own way of opening up a different world, which may not have been written in words.

Take the example of ‘Jani Mhane,’ a work by Sharvari Deshpande, who is one of our team members. ‘Jani Mhane,’ written in Marathi, is originally a 12th century work. However, the illustrations made by Sharvari are rooted in contemporary times.

Binit (P): Now that we have talked about stories inspired from daily lives, how are you thinking of writing them for children? Although some literature is classified as children’s literature, we like to think that even adults can read and enjoy these works. How can these themes related to daily life be simplified and also be written for children?

Lokesh (BJ): We are always thinking about this. For example, Samanta Raita’s story on the BlueJackal website, titled ‘Moon on an Old Scooter,’ has been designed as a web comic. It is folklore, retold in a contemporary way. If you look at this story, the structure is rather simple. It contains a certain amount of light-heartedness.

However, it cannot just be seen as children’s literature. It also becomes more significant when Samanta tells the story because he belongs to the Saura tribe from which the story emerges.

Shivangi (BJ): There is another such invited story, titled ‘The Secret of Erdmannlistein’ by Wanda Dufner, on our website. It comes from her own memory of going for a picnic as a child. It also speaks of the loneliness some children face when they don’t fit in. That is also as much a story for children as for adults.

Both ‘Moon on an Old Scooter’ and ‘The Secret of Erdmannlistein’ were sent to us in response to a BlueJackal open call. It invited artists and contributors to bring legends, myths and folktales from their contexts and retell them in comic, picture book or visual story formats.

Lokesh (BJ): We try to look at many things while trying to represent or talk about challenging and difficult topics in children’s literature. We are inspired by the many examples of other authors and illustrators around us.

Some time back there was a controversy over this book in Jharkhand. Antara released this book called ‘Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire: Adventures in Champakbagh’ by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar.

‘Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire’ is a book for children and young adults like many others such as the ‘Aditi and Her Friends’ series by Suniti Namjoshi. It is a very interesting story about a dragon who is adopted and brought up by some children.

At one point in the story, the children have run out of food at home and are very hungry. The dragon catches some mice and roasts them with his breath and the children eat the mice happily.

The writer does not mention anywhere in the story that the children belong to the Musahar community. However, it is interesting to note how delicately the author has introduced a layer to the children’s story.

Children from a different context can now understand or get exposed to different kinds of food that can be consumed by people either out of choice or by necessity!

Siddhi (P): This way of including insights of people through open calls is very interesting. Your team has many books which have been written and illustrated by the same person. How do these books come out differently? Also, you have talked about simultaneously maintaining and dissolving the strategic boundaries between writers, illustrators and researchers. Please tell us more about that.

Lokesh (BJ): I think it keeps changing from book to book as to what kind of collaboration it is going to be. When we are writing a story by ourselves, then realities are different as compared to a retelling of a story.

Shivangi (BJ): Through our collective practice and work, we try to break the silos of being a single type of writer or illustrator or a researcher. Also, art is not something a selected bunch of ‘qualified’ people should be doing. The contributors we invited were also not necessarily all artists. All of us from the team come from a visual arts background. We keep realizing that there are limitations to this too.

Surya (P): How do you see yourself in the future, let’ say ten years down the line?

Lokesh (BJ): Not that we have a definite answer to this question. Still we try moving ahead with some shorter term goals. We also think about how and where we take not only our publications but also share our ideas and thoughts. In this regard, we sometimes do workshops with different organizations and age groups. During the past many years, independent comics, zines and picture book publishing has increased across India.

Many of us, who are collectives as well as individual makers and publishers across India, have come together to create a platform called ‘Indie Comix Fest’. It is a space where independently published comic books can be showcased and sold. It also aims to create a community of creators and likeminded people. BlueJackal had been coorganizing the Delhi chapter of Indie Comix Fest since the last few years, along with a group of comics creators and publishers.

We also try to approach libraries, so that our books are read by many people. Most of the time it is done through word of mouth. Like how we reached Prayog, TCLP, Muskaan schools etc. We are trying to reach the remote regions too, where work of social change is happening at the grassroots. So, we are eager to work in such places either through workshops, books and the content created by us.

Surya (P): What suggestions would you give to other organizations, libraries, educational spaces or individuals working with children’s literature, especially when one is beginning to explore this area? It becomes very tough to just share a booklist only because we have curated it. Our context and purpose may or may not be the same or best suited for some other place. So, what would you do in such a situation?

Shivangi (BJ): First, I think we ourselves need to learn from organizations about their processes as how they build their collections and prepare lists of books that needs to be added. What should be the screening process? I have to personally say that we should have an online resource list that could be accessed by anyone. This list will have information about the latest releases or the books available in each genre or theme, for example the latest books released under the theme of gender in children’s literature and so on.

I feel this would be a very unique and interesting way to explore different collections under different categories and then select the books that we want to have in our collection. In some ways this type of categorization is already done by different libraries on an organizational level. However, it would be really nice to have a platform where this type of categorization and listing is done on a larger level for us to learn and explore.

Lokesh (BJ): I would like to add that often children take interest in multiple things and disconnected areas simultaneously. And a library can be an amazing place where this aspect can be playfully engaged with.

Surya (P): We are also learning by making mistakes. For example, whenever we decide that a book should be in a particular category or it is related to a particular thing, but then after sometime we revisit it and we might then decide that now this belongs to some other theme. So, in this way, we buy books from different publications, we read them and then decide about the age group, theme and genre it can be categorized under. This learning has evolved from various places and sources.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!