Learning to Read is Reading to Learn – A Brief Journey of Ideas in Early Literacy Education in India

In ‘Learning to Read is Reading to Learn’ Shailaja Menon provides a brief history of the key ideas in early literacy education in India.

India’s National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 (GoI, 2020) identifies Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) as one of the key goals of the policy. Following this, the government released the NIPUN Bharat document (GoI, 2021) identifying various aspects and learning outcomes related to these domains. The work of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) working in education has also understandably intensified or redirected itself towards these aims.

It goes without saying that literacy has the capacity to do much for societies and for individual lives. The caution is that it also has the danger of doing very little and of maintaining the status quo if we don’t understand it well. Literacy, in itself, is nothing more or less than how we understand it, use it, or teach our children to use it. So, what is literacy? Broadly and intuitively, many educators assume that literacy is the ‘ability to read and write’. ‘With comprehension,’ some will add hastily, ‘with comprehension’.

But, what is this ‘ability to read and write’? When pushed thus, it turns out that in popular imagination, ‘to read and write’ means to be able to handle scripts competently – that is, to be able to decipher or decode the script fluently and to spell accurately. Historically, this is called the ‘simple view’ of learning to read (Gough & Tunmer, 1986). When people decode the script accurately, they turn the script into oral language. Since they already (presumably) understand the oral language, they will automatically understand what they are reading. Thus, comprehension is the result of the script being turned back into oral language by the reader.

However, since the 1970s and 1980s, scholars have shown that reading and writing involve far more complex processes. Comprehension does not occur at the end of decoding, but in good comprehenders it happens before, during, after – and at all points of the reading and writing processes (Anderson & Pearson, 1984). How, you may wonder, can comprehension start before we start reading? Meaning-making enters the process when the reader understands the relevance of the task, sets appropriate goals and activates what she already knows about the topic.

For example, if I see a newspaper headline saying, “Maoists in talk with government in Chhattisgarh” – I would automatically bring to my reading my knowledge and opinions about Maoists, about Maoists in Chhattisgarh, about how the current government functions in Chhattisgarh, and how such talks have gone before. I would subconsciously or consciously hold all this in my active attention even before I started reading the body of the article! Meaning-making processes would also interact continuously with my reading, rather than politely waiting in the sidelines until I had finished deciphering the script. What is true for adult readers, is true for younger readers, too. Comprehension interacts with and impacts the child’s reading throughout.

Further, comprehension processes can be invoked in multiple ways, and at multiple levels. At a minimum, it includes the ability to read the lines, to read between the lines, and to read beyond the lines. This means, we need to comprehend what is stated (reading the lines); comprehend what is left unstated or implied (read between the lines); and connect the reading with our lives and respond to it (read beyond the lines). Imagine that a child reads the sentence, “It is good to stand on hot tin roofs on summer afternoons”. As educators, we would hope that a child would not just read this sentence with understanding, but also ask herself: What evidence has the author presented for this statement? What does my experience tell me about this? Readers must learn to read and respond to texts critically, not merely to understand what they are saying!

Now, if this is what we mean by the term ‘early literacy’, then it has enormous value to offer to any society in which children are being helped to become literate. In such a conceptualization, ‘learning to read’ is not dichotomized from ‘reading to learn’ – but includes higher order learning and meaningmaking at every step of the process. But, if we mean teaching the script (without much of a vision of the relevance of the script to children’s lives) – then more literacy by itself won’t necessarily create a better society!

At the heart of the debate on how to teach children to read is an attempt to figure out how to teach children the relationships between symbols, sounds and meaning. Do we teach the symbols first, then sounds? Do we teach the symbol-sound combinations together, and will meaning then follow? Do we teach meaning-making first, and then symbol-sound recognition will follow? Do we teach them all together? This is, in essence the dance of early literacy – how much of which of these aspects? When? In which combinations?

Historically, it was presumed that the beginning reader understood the oral language of which she was trying to acquire the script. In Indian contexts the focus was then on teaching the child to read the varnamala and the barakhadi. Children would learn to read two and three akshara words, then sentences. Initially, the words would be presented without maatras, but slowly the words would include maatras of increasing complexity. Only after the child had mastered the varnamala, would she be given little passages and poems to read, faithfully responding to the back-of-thechapter questions and vocabulary exercises as instructed to by the teacher.

Even when children learned new words or answered the comprehension questions, they were passive. No one asked them what they were thinking, whether they had liked what they read, whether they were connecting it to anything in their lives or to other books, or whether they ever used the new words whose meanings they were learning by rote. No one actually asked children to think. In fact, thinking for themselves could get children into trouble. Because then, they might not faithfully reproduce what the teacher had made them write down in their notebooks from the board.

Why did we ever get into such a meaningless way of teaching reading and writing? Shobha Sinha (2012) referred to such a process as ‘reading without meaning’? If we look historically for reasons, it is possible that prior to the 19th century, certain groups of children enrolled to learn reading and writing for particular, well-defined purposes. These goals included, for example, accessing the scriptures, or learning functional skills for some trade. The skills and capabilities that needed to be developed, and what they would be used for, were presumably more readily accessible to the minds of both teacher and students.

However, as society transformed, at least two aspects of this equation shifted. First, the spheres in which literacy was used expanded rapidly. This led to a concurrent shrinkage in spaces where literate capabilities were not necessary. These processes resulted in some confusion about the wider range of capabilities that literate individuals now needed to have. Second, our vision of ‘Education for All’ meant that every single child needed to be brought into this sphere of widening, diffuse, rapidly transforming literate activities and capabilities. Our old (limited, but functional) understandings of literacy and old methods of instruction are simply not adequate to meet these new social and economic realities!

It is not that meaning-making was entirely disregarded in earlier methods of teaching reading. However, meaning-making itself was conceptualized in rather limited, lower-order ways. In early British primers for English from the late 19th century, for example, we see injunctions to teachers to introduce a few letters of the alphabet at a time and to quickly contextualize these letters in words. (See Box 1). Presumably, this was done in order to make the introduced letters meaningful to the child.

The text shown in Box 1 uses the ‘phonics method,’ which focuses on teaching the sound of letters explicitly and systematically, and contextualizing these letters and sounds into little words. Also evident during the colonial period was the ‘Direct Instruction Method,’ where children were immersed in the functional usages of language. Deriving from this, ‘Do and Say’ methods were in use, with, for example, the teacher saying ‘Stand’ and the pupils responding ‘We stand’, while actually standing (see Box 2).

These are a few examples of introducing meaning-making to early reading – albeit what might be considered as lower-order meaning today. These examples are drawn from English textbooks, where it was presumed that native children might need support with understanding the oral language. Hence, attempts to include functional oral language were present. While learning Indian scripts, on the other hand, it was assumed that since the child already understood the oral language, such functional immersion in the spoken language was not necessary.

In this context, the approach developed in the late 1960s and 1970s by Pragat Shikshan Sanstha (PSS) in Phaltan, Maharashtra under the leadership of Dr. Maxine Berntsen (see Berntsen, 2020) was very innovative, because it deviated significantly from traditional, script-based modes of instruction. Dr. Berntsen combined theoretical understandings from the Western world with the specific nature of Indian scripts to develop a method to teach early literacy to Marathi speaking children. Her method assumed the following:

- The linkage between letters and sounds does not happen automatically for many children. This must be fostered systematically, keeping in mind the specific characteristics of that script;

- It is important to approach ‘meaningmaking’ in terms of emotionally significant content for children (Ashton-Warner, 1986). Thus, it is important to include references to people and things that are from the child’s own context and have value and meaning for the child.

- A variety of planned opportunities and activities are needed for children to acquire the relationships amongst symbol, sound and meaning with fluency.

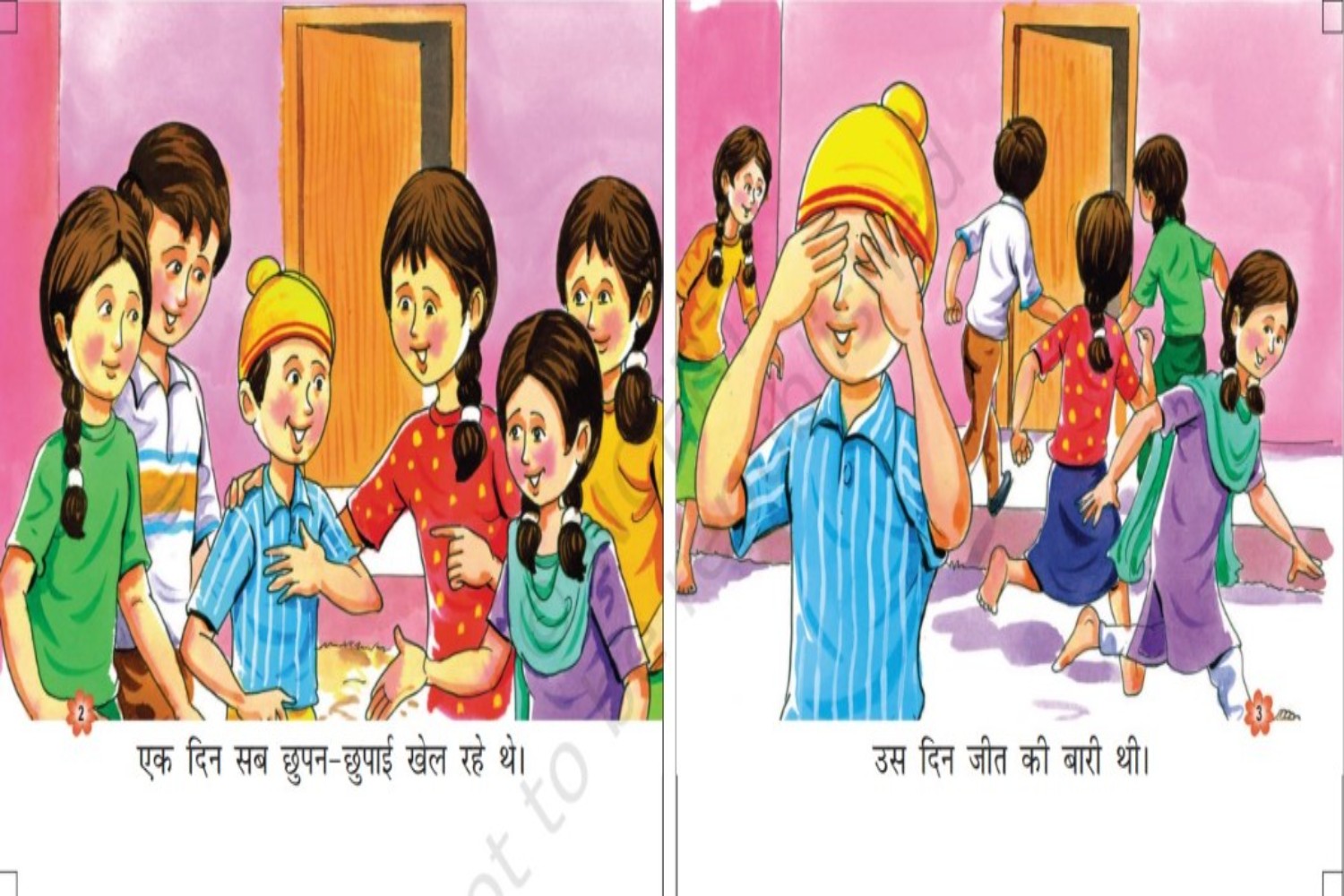

With this in mind, textbooks were developed that introduced children to a small set of aksharas at a time. These were placed in the contexts of sentences that were presumed to be meaningful to the child (see Figure 2).

Even while Dr. Berntsen was experimenting with new approaches for teaching early reading and writing to Indian children, a revolutionary new paradigm for teaching reading to children had come into prominence in the West. Called the ‘Whole Language Approach’ (Goodman, 1967), this paradigm proposed that children learned to read and write naturally, as they learned to speak – through immersion, modelling and implicit learning.

Immersion meant that children needed to be surrounded by print-rich environments. Modelling meant that children needed capable and competent adult models who showed them how to navigate through the worlds of literacy. And incidental or implicit learning meant that children didn’t need to be taken through a well-laid out or systematic sequence of phonics instruction. They would pick it up through multiple ways.

Children could use the context of the sentence to figure out how to read a word. Or, a child could learn the sound that the letter ‘s’ made while exploring the spelling of her friend, Sunita’s name. Or else, a child who is interested in butterflies might learn the spelling of that word by reading many books about butterflies or by asking an adult for help.

Phonetic input, according to this theory, was just one of several important inputs into the reader’s brain. Readers also used cues based on vocabulary and grammar to figure out unknown words. Whole language theorists and several affiliated paradigms, for example, that of ‘emergent literacy’ (Teale & Sulzby, 1986) brought in the following influential ideas to the teaching of early literacy:

- Literature-based reading curricula – even young children who couldn’t yet decode the scripts should have high quality literature read aloud to them;

- High-quality discussions – that were about more than ‘understanding’ the content, but included discussing connections, implications, predictions, interpretations, responses, and so on;

- The importance of the child’s background knowledge – what was taught should always be connected to what the child already knows;

- Welcoming of children’s ‘emergent’ reading and writing attempts – encouraging children to browse through books that they couldn’t yet decode and encouraging them to represent their thoughts in writing through drawings, scribbles and invented spellings;

- Integration of listening, speaking, reading, writing and thinking – the recognition that all these capabilities developed simultaneously and must be taught in an integrated manner in classrooms.

never widely adopted in classrooms across the country. NCERT, under the leadership of Professor Krishna Kumar established the Early Literacy Cell during the first decade of this century (now merged with the Department of Elementary Education). Scholars affiliated with this cell conducted the Mathura Pilot Project that implemented a whole language curriculum in 561 schools in five blocks of Mathura district in Uttar Pradesh, and showed positive outcomes in terms of student learning (GoI, 2012- 13). NCERT also developed a story-based textbook series called the ‘Barkha series’ that was inspired by ideas from the whole language paradigm (see Figure 3). But despite these attempts, by and large, the teaching of early reading and writing clung tenaciously to the traditional methods described earlier.

Meanwhile, in the West, the Whole Language Approach was not without its opponents. Advocates of phonics-based approaches took on the whole language paradigm from a variety of angles and perspectives, attempting to debunk many of its key assumptions. Finally, in 1998, an eminent panel of scholars drawn from across the U.S. concluded that many children do not pick up the sounds and symbols of the English alphabet without explicit and systematic instruction (Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998).

Learning to read and write, it turned out, is not like learning to speak. It needs careful and prolonged letter-sound instruction. This is not applicable just to the learning of English. In India, Sonali Nag (2007) has shown that children take multiple years to learn to read and write Indic (alphasyllabic) scripts. In fact, her data suggest that learning to read and write Indic scripts may be a longer process than learning to read and write English in Western contexts!

So, where does all this leave us? Since the Whole Language paradigm was wrong on certain counts, are we wise to stick to the traditional varnamala approach? Whole Language was wrong about the teaching and learning of phonics. However, it had many insights of value to offer, which are important to retain. Therefore, contemporary educators favour what is referred to as a ‘balanced’ or ‘comprehensive’ approach to teaching early literacy.

The comprehensive approach:

- Pays equal emphasis to various aspects of reading and writing, such as, the teaching of letter-sound relationships, vocabulary, writing, oral language, comprehension, and so on.

- Asserts that listening, speaking, reading and writing must be taught together and in conjunction with high quality thinking.

- Uses a variety of teaching methods, such as reading aloud, guided and modelled and independent writing, shared and guided reading, independent book browsing and reading, and so on.

- Recommends a variety of curricular materials for the teaching of literacy, such as, high quality literature, akshara cards and games, worksheets, tiles, sand, etc.

In tracing important influences on early language instruction in Indian contexts, it would be remiss to not mention the pioneering attempts by Ajit Mohanty and colleagues (Mohanty, Mishra, Reddy & Ramesh, 2009) to develop curriculum and pedagogy for Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTBMLE) for children speaking tribal languages in Odisha. Mohanty et al. showed how children could access the multiple languages of their surroundings (their own mother tongues, the regional language and English) in a meaningful manner.

They challenge us, as a nation, to consider how mother tongues of children can be used to maintain and nourish the less powerful languages. This will help these langauges not just survive, but thrive in contemporary Indian societies. The mother tongues of children speaking less powerful languages such as those of the ST communities, thus, need not just be used to transition children to the more powerful languages.

The approach taken by several influential contemporary organizations and individuals working in India are included in this volume. Many of them are pioneers in imagining and implementing the balanced approach in Indian contexts. Noteworthy contemporary efforts that have expanded upon earlier efforts include:

- Organization for Early Literacy Promotion (OELP), which uses a systematic and meaningful approach to teaching the Devnagari script to children in northern India. In addition, it has a deep focus on using literature and complex conversations in early language classrooms and gives children opportunities for meaningful writing, valuing their emergent writing attempts. OELP has also done pioneering work with engaging communities meaningfully in early literacy instruction.

- Learning and Language Foundation (LLF), which acknowledges that in India we cannot assume that young children understand the oral language of the scripts that they learn. Hence, mother tongues must be used in the early instruction of children, and curricular materials need to be developed that permit the meaningful use of mother tongues, especially in Grades 1 and 2. LLF is sympathetic to the MTBMLE approach proposed by Mohanty et al. However, in large-scale implementation efforts with governments, it has been restricted to using mother tongues in an early-exit transitional model in which children ‘exit’ from the mother tongue to the regional language by Grade 2.

- Room to Read’s effort to bring a library to every village, and to provide a framework for implementing balanced literacy curricula in government schools.

- Various NGOs, including Gubbachi, have developed ‘bridge’ curricula and methods to enable children who are out of school to start or resume formal schooling.

As we look back, we have come far, and covered much distance in our collective understanding of early literacy over the past few decades. For one, we have understood that it is a priority for education. For another, we have agreed that literacy without meaning-making is not terribly useful. We have only just begun to understand that learning to read is reading to learn. We have also begun to forge professional alliances to strengthen this domain and to articulate our collective thinking and positions (e.g., Position Paper for Early Language and Literacy, Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development, 2016). Finally, we have an NEP that identifies this as an area of national priority.

Despite these signs of progress, we are still in a very nascent stage in terms of working together in this domain. We need to be vigilant against our collective historic tendency to understand reading and writing in narrow ways. The most recent trend in this direction has been to aim for developing oral reading fluency, understood in terms of the number of words correctly read per minute. Oral reading fluency norms, when used knowledgeably in the context of a balanced literacy curriculum, can be helpful indicators. Taken out of context, it can be disastrous to a nation that is only beginning to understand literacy as a broader construct than script decoding. We also sorely need evidence and data-based approaches to the teaching of different scripts and languages.

The teaching of multiple languages marked unequally by power is a burning question. While NEP 2020 calls for ‘mother tongue based’ teaching, it often uses this term interchangeably with ‘regional language’ instruction, leaving us unclear about the political clarity or will behind this injunction.

Work on specific learning disabilities, including dyslexia, will add much to our understanding of how to supplement balanced literacy classrooms to ensure the success of all children in accessing literate worlds. Most of all, we need informed professionals who understand how to go about accomplishing the broad and evolving aims of language education.

How do we proceed? The path ahead appears to be complex, challenging, and fraught with uncertainties. However, there are also enough signs for cautious optimism. Perhaps, as the poet, Theodore Roethke put it, we will ‘learn by going’ where we have to go…

References

Anderson, R. C., & Pearson, P. D. (1984). A schema-theoretic view of basic processes in reading comprehension. In P. D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. I, pp. 255- 291). New York: Longman.

Ashton-Warner, S. (1986). Teacher. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Berntsen, M. (2020). The Pragat Shikshan Sanstha (PSS) approach to teaching literacy in Indian languages: Parts I & II. In S. Menon, S. Sinha, H. V. Das, & A. Pydah (Eds.). (2020). Teaching and learning the script. Early Literacy Initiative Resource Book Series. Hyderabad: Early Literacy Initiative, Tata Institute of Social Sciences & Bhopal: Eklavya Foundation.

Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development (2016). Early language and literacy in India: A position paper. Delhi: Ambedkar University.

Goodman, K. S. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6(4), 126–135.

Gough, P.B. & Tunmer, W.E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10.

Government of India (GoI, 2012-2013). Endterm Survey Report: Mathura Pilot Project. New Delhi: National Council for Educational Research and Training. Retrieved: https://ncert.nic.in/dee/pdf/FINALETS10.12.13.pdf

Government of India (GoI, 2020). National Education Policy. New Delhi: Ministry for Human Resource Development. Retrieved: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

Government of India (GoI, 2021). National Initiative for Reading with Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN). New Delhi: National Council for Educational Research and Training. Retrieved: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/nipun_bharat_ eng1.pdf

Mohanty, A. K., Mishra, M. K., Reddy, N. U., & Ramesh, G. (2009). Overcoming the language barrier for tribal children: MLE in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa, India. In A. K. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson, & T. SkutnabbKangas (Eds.), Multilingual education for social justice (pp. 278–291). Orient Longman.

Nag, S. (2007). Early reading in Kannada: The pace of acquisition of orthographic knowledge and phonemic awareness. Journal of Research in Reading, 30(1), 7-22.

Sinha, S. (2012). Reading without meaning: The dilemma of Indian classrooms. Language and Language Teaching, 1(1), 22-26.

Snow, C.E., Burns, M.S., & Griffin, P. (eds.) (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Teale, W. N., & Sulzby, E. (Eds.) (1986). Emergent literacy: Writing and reading. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!