Reconsidering assessment in the arts: dismantling the veil of ambiguity

In the essay titled “Reconsidering assessment in the arts” Nisha Nair foregrounds the importance of processual aspects of learning the arts, the ways in which they can help develop skills and attitudes that can inform the learning of other subjects, and the role of assessment as a central tool in this endeavour.

Conversations around assessments— both formative and summative—are a mainstay of education discourse. Education policy documents and mandates are replete with references to the need for clear and comprehensive assessments. Educational institutions, whether schools or NGOs administering educational programming, driven by obligations to prove the efficacy of their interventions to themselves and to higher governing bodies, clamor to institute these assessments. Assessments, after all, are intended to reveal where students are at in relation to set educational and learning objectives. They are also expected to reveal the gaps in students’ learning to be filled thoughtfully.

Despite the importance accorded to assessments, when it comes to the arts, conversations around assessments are either conspicuously absent, the arts being deemed as too subjective to be assessed, or, they tend to be enmeshed in archaic and exclusionary notions of ‘creative’ talent. The former is evidenced in the execution of a plethora of ad hoc art activities that lack a clear roadmap for deep and purposeful learning, with prompts that suggest a do-whatever-youwant attitude.

The latter often takes the form of didactic and constraining art activities, evidenced in prompts such as, “We will be making a painting of Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night,” which presume and celebrate some students’ ‘innate’ ability to replicate works of art regarded as ‘masterful.’

The consequences of such misplaced (yet, assumed to be benign) notions surrounding assessments in the arts are dire. These justify art as an unnecessary frill in relation to the more ‘serious’ task of educating students. They also perpetuate an art-for-some versus art-for-all narrative. We do not have to look too far to witness their widespread impact.

Over the course of my work in education in and through the arts, as teacher, teacher trainer, curriculum developer, and education and nonprofit administrator, my desire has been to create inclusive learning environments within which all children with diverse learning capabilities can thrive.

Combined with my desire to elevate the position of the arts in education and to increase access to meaningful arts instruction for all children, this has quite instinctively driven me to (re)consider notions of assessment—how they are conceived of and administered.

Moreover, as an education researcher, my work in exploring sociocultural values, beliefs and ideologies inherent to education policy recommendations and pedagogical practices employed, leads me to consider how these values, beliefs and ideologies, impinge upon enduring (albeit problematic) notions of assessment in general, and arts assessment in specific.

In this article, I pose two essential questions and share some reflections for further contemplation to help reimagine arts assessment as a means to improve arts teaching, enhance students’ arts learning and motivation, and offer tangible evidence of arts’ impact.

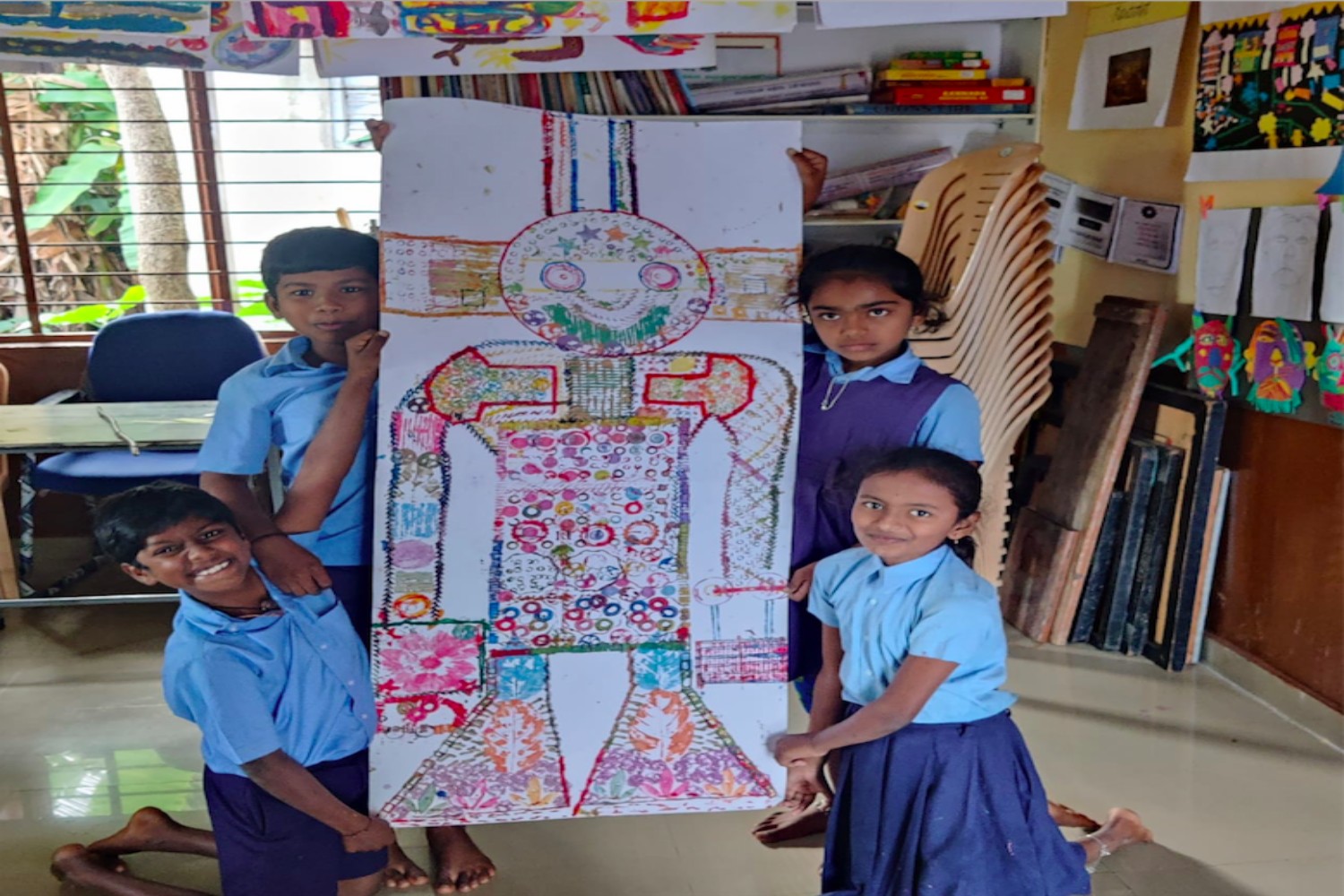

Implications may be drawn for the field of education in general as well. Examples, where relevant, are drawn from the work of ArtSparks Foundation—an arts-based educational nonprofit organization—and its use of assessment to support students’ learning in and through the visual arts.

How are conversations around assessment tied to notions of student learning?

There is a historical precedent of thinking about assessment in terms of assessment of student learning rather than assessment for student learning. This is not just a matter of semantics. Instead, it reflects a certain set of assumptions about the role of students in relation to the teacher and the broader educational enterprise.

In the former instance, conversations surrounding the assessment of student learning conceive of students as passive recipients of the process. Assessments are done to students, after the completion of a learning task, by the assessing body.

The latter has sole access to the criteria for learning that determine students’ grasp of a concept or gaps in their learning. Assessments viewed from this lens tend towards practices that deny students agency in the process. Instead, these expose them to the judgement of others.

In the realm of arts instruction, we may conceive of a number of alternative scenarios that result from such a notion of assessment of student learning. For example, on the one hand it can lead to judgment-filled practices that promote conversations around good and bad art, right and wrong technique, those with talent and those without.

On the other, it can lead those opposed to the practice of passing judgment on children’s art to renounce ‘instruction’ and assessments altogether, opting instead for a more unstructured, unguided approach to art-making.

Additionally, in an effort to ensure that all students succeed, albeit superficially, it can also result in formulaic instructional practices that offer step-by-step procedures for students to follow, often blindly, with 40 students in a class creating 40 near identical works of art.

As an alternative, assessment for, or in service of, student learning conceives of students as active participants in the assessment process. It makes transparent to students the criteria for assessment. These are articulated through clear learning objectives.

They are also reflected in checklists and/ or rubrics to which students are provided access. Learners can then reference these to self-assess and guide the progress of their own learning. This is supplemented by multiple opportunities for students to give and receive feedback and revise their work.

To offer a concrete example, at ArtSparks, for a given multi-session sculptural project spanning approximately eight sessions, students were asked to create a free standing sculpture.

Criteria for learning included the following. The sculpture must be at least two (2) feet tall. It must be able to balance despite its height. And it must be visually distinct from all sides showing high-levels of experimentation with the materials (in this case, cardboard and paper).

These criteria were conveyed to the students, each armed with a rubric in hand to reference as they worked on their sculptures. Furthermore, the rubric also articulated the levels associated with each criteria. In other words, what would students need to consider in order to exceed each of the three criteria, versus just meet them?

Exceeding the criteria of balance, for instance, was defined as, creating a sculpture that is structurally sound and balanced, resistant to any force exerted upon it. This is in comparison with what it meant to simply meet the criteria: creating a sculpture that appears to be balanced, but does not withstand force applied to it.

Throughout the process, students were given multiple opportunities to pair up with their peers. They were also encouraged to use the rubric to give and receive concrete, constructive feedback on one another’s sculptures-in-progress.

Most importantly, students had the opportunity to apply the feedback received as they made revisions to their sculptures. What percentage of students in this class, do you think, exceeded the criteria set for demonstrating balance?

How are conversations around assessment tied to notions of teaching and the role of teachers?

The role of a teacher is well established in the institutional structure of Indian society. And, there exists a broad consensus in the culture about what this role entails—teacher as knowledge bearer; teacher as instructor, guide, facilitator—particularly in relation to students.

Operating from this standpoint, assessments are often viewed as a means for the all-knowing teacher to gauge student learning, identify gaps in learning, and act in accordance to remedy students’ learning deficits.

Rarely are assessments used by teachers as tools for self-reflection, to contemplate their own teaching practices from one lesson to the next, identify and ameliorate gaps in facilitation that may compromise fulfilment of articulated curricular goals and student learning objectives, and design more coherent instruction.

So, how would this manifest in a learning environment, or, more specifically, in an artsbased learning environment? Let us stay with the example of the multi-session sculptural project at ArtSparks. It is not unusual for our facilitators to, in the course of the project cycle, miss out on providing students with essential opportunities to understand more deeply, and test out for themselves the nuances associated with the concept of balance, which is critical for building their sculptures. As a result, at some stage of the building process, it becomes evident that a number of students have structurally weak, tentatively balanced sculptures, which conflict with their ability to more fully realize that specific learning objective.

Awareness of the gap in their facilitation, by referencing the assessment rubric and associated criteria for learning, enable the facilitators to introduce a bridge lesson. This provides students with crucial opportunities to experiment, in a more targeted manner, with building techniques related to concepts of balance and structural integrity. Additionally, in order to further support their students, the facilitators introduce a wide variety of image samples from sculpture to architecture and more, which demonstrate these concepts in more visible ways.

It is important to reconceptualize the role of assessment not only as a tool for assessing student learning, but also a tool for teachers to reference in relation to their facilitation practices. This is, of course, predicated on the notion of teacher-as-learner.

They have to be encouraged to learn from any missteps taken without the fear of judgement from administrators. They also need to be empowered with prerequisite knowledge and agency to take action of their own volition, and course-correct in the ongoing cycle of teaching and learning.

And, finally, a few parting thoughts and considerations

- Designing coherent curriculum and instruction in the arts involves asking the question – What types of art-making activities would best reveal the learnings embedded in the arts, as well as high levels of thinking, in engaging and age-appropriate ways?

- Designing coherent assessments in the arts involves asking the question – How can I identify and clearly articulate key criteria for learning that are readily and visibly demonstrable, as my students make artworks, highlighting for me, the teacher, students’ understanding, or lack thereof, of a concept, while the project is ongoing?

- Following impactful assessment practices that help both teachers and students involve answering questions such as – How am I doing? Where am I going with this task, project, etc.? Where am I now? How do I get to where I want to be?

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!