A historical survey of assessment models in India: potential and challenges

In a comprehensive piece, Jacob Tharu provides a survey of models of assessment in the country, and the ways in which they have evolved here.

Having been a teacher of assessment, addressing teachers for a long time, I will try and clarify one or two concepts in assessment. Examination is the big bad thing we’ve got under control because CCE isn’t coming and CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) has abolished the board. I’d like to clarify one or two points in relation to that – what assessment is, or what measurement is, or what testing is, which I think we don’t pay much attention to because we take it for granted.

As has been said rightly, we have an examination system in this country, not an educational system. Now an educational system is slowly coming out of the crevices and asserting itself. We are in that transition. All of us, as students in high school, and some of us who studied English, have written character sketches based on stories and novels. What happens there? We take what a character or person does – or says, if it is drama. Shakespearean drama is only what a person says. They don’t do things, they talk about things. From that we make an inference about them – about a certain enduring personal quality. So we have the character of Lady Macbeth, of Hamlet and Lothario and so on.

This is very important. We are looking at performance and making an inference about a personal quality which causes that performance or underlies it. This is exactly what we are doing in testing. We’ve got to be very, very clear about this, because the fact that there is something called behaviourism – a big, bad evil – and we want to get it out of the way, is a wonderful thought. But if you want to use the word ‘assessment’, you’ve got to remember that this is what we are doing. The test is basically a means of eliciting a performance. So the question paper is the means of obtaining an answer script. It is what the assessor does with the evidence of performance in the answer script that constitutes evaluation. We keep on talking about paper setting and books and so on. For many, many years, we have encountered that, but we never really paid enough attention to the whole process of how assessment was done.

There is this indirectness in terms of what we observe. We can’t observe what is inside, directly, so we have to find what is called an observable indicator. This is nothing to apologise for because even a physicist can’t do anything better. Body temperature is measured by putting a thermometer in a child’s mouth and then looking at a column of mercury. It is this column of mercury which allows us to make an inference.

If we are using the mode of assessment, which is an empirical process, we are finding an index of it – and that index is performance. If you don’t like the word behaviourism, don’t call it behaviour. But this is something that we have to be very careful about.

In the field that I have been working, I have always argued that there are two traditions. One is that of psychological testing, which is actually the parent discipline, psychometrics, in which I had my basic training. Psychological testing relates to enduring personal qualities – intelligence, attitude and so on – and this is where the notion of reliability comes in. Because we see a test applied to somebody, an inference is made and a score is give to the person. It shouldn’t be very different two weeks later, or three weeks later. Then if someone else comes along and gives the person a test, it should be pretty much the same. What we are assuming is that there is something fixed. That is a big statement.

The whole theory of reliability in psychological assessments is based on this – laughable – assumption that human personal qualities are stable. How deeply we believe in this, of course, is evident every day. Because every time anybody opens his or her mouth and says something about merit, what are we talking about – some sections of our society which have merit and some sections of society which don’t have merit, right? So we have to be very careful about this assumption.

That is about psychological theory. In education, there is a difference. Broadly, our primary focus is on learning – and the problem is that learning, by definition, is something changing, something elusive, emerging. So what is a test of learning? This is a fundamental dilemma in educational measurement, which has never really been answered.

What are our examinations? We observe high school students between the 21st and the 28th of March and we make some inferences. And for the rest of his or her life, this is a caste mark – third class matriculate. Assessment, if it becomes recorded and personal and stabilized, is like giving an attribute to a person. This is really a fundamental problem in the assessment of learning – that we have to find something that we have to rate. We observe learning at a particular time, yes. But what are the inferences and what are the categorizations that we can make of it? That is another fundamental issue that we have to work with.

We also need to reflect on what we do operationally. The term ‘psychological evaluation’ doesn’t come in any textbook. Many of you, I think, have worked in education so you have psychological testing, only, with the prefix ‘education’ – educational measurement and evaluation. Psychological evaluation is something which may be done for a particular purpose by a set of specialists, but normally we don’t talk about psychological evaluation. So I would say that psychometrics is basically a descriptive discipline. We use its findings to say some people are intelligent, some races are intelligent, or unintelligent… The basic operation is one of description.

In educational testing, it seems to me, right from the beginning, we are making judgements of adequacy. Have you learnt what you were supposed to learn? Whether we call them marks or whether we call them grades, the whole activity in education is that intervention for which we expect some outcomes, and the responsibility is on the learner to demonstrate that. How intensively, how forcibly or how unkindly we do it is a matter of choice. But we need to reflect on this. So when you say objectives – learning outcomes – we don’t have to buy Benjamin Bloom but we are thinking in terms of expected outcomes. That is another dilemma that we have in the field of assessment.

In a pedagogic theory, we are saying we believe that these things are desirable for children as we – at least in modern education – draw them into society. It could bring them to be able to contribute to society, to change society, to live a meaningful life and so on. We are also saying that these are the mechanisms, the means, by which we will provoke that learning. That is the best we can do and we get new theories, new understanding and new equations. But as soon as the term assessment/evaluation/ testing /measurement comes into the picture, we are safe. We want you to demonstrate this outcome. So what is a hope, a theory, an expectation, becomes a demand. By evaluation, we are applying a criterion to value this performance and, of course, draw inferences about a person’s ability or qualities or whatever else. This objective to value the criterion is something that appears to me to be inescapable, but that is where we need to reflect.

This is very important in our country because we say we have an examination system. We have to go back to the history of examinations here. Right from the beginning, examinations have been external. The British left us with a system that they don’t have – at least not at the same level. I was looking through some early history of education and found that even in the universities of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, the effective power of the examination in the early stages stayed with London. And of course, we see it now in our educational boards and in our affiliated universities.

A great deal of what we talk about in terms of teacher growth and the rest of it do not make any sense. College teachers in this country are teaching somebody else’s syllabus and trying to guess somebody else’s question paper. This is what a college teacher does during a career of 30 years. So we have academic staff colleges and we have teacher development, but this is the fundamental fact. The honest thing for a college teacher to do would be to get a guide book and help a student pass the exam!

I had the privilege of working at IIT Kanpur and CIEFL [Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, now renamed as EFLU (English and Foreign Languages University)] which are fully autonomous. Like in American universities, you set every question paper yourself, you mark it and type it yourself. But we have this external examination system that runs through our degrees. So paper setting is something that somebody does remote from the field of assessment.

With all good intentions, even from DPEP (District Primary Education Program) times and this sort of thing, the idea of cluster-level, mandal level, block-level paper setting is a good means of quality control. But it is not located where the teacher is. It is not located where the classroom is. That is another deep-set tradition we have which, now with internal assessment and school based assessment, we are moving away from. We have a long way to go.

But there is another factor that again goes back to our history, starting with the introduction of modern education in colonial times. That education was to prepare a small group of people to function as the lower levels of administration in the British Raj. It was for a very small number, which means that education was basically selective – examinations had this filtration factor, and examinations subsequently have always had this.

Long before the special entrance tests came, the IIT-JEE was the most prominent and the first one, and then the CAT for management school admission. Then various states brought in their tests – the EAMCET for engineering, agriculture and medicine and the state professional courses and all that. But prior to that, what was the matriculation exam? It sorted out those who could go further from those who couldn’t, like the now infamous 11+ examination of the British, which was introduced in 1944 to separate people – those who could go to Grammar School and those who couldn’t.

Certification for the purpose of some sort of categorization is not bad in itself, if you have a qualifying test. So if you want to get into the Services Selection Board or the National Defence Academy and so on, you have to pass a certain level of medical fitness and other things. But that is a yes/no description of categorization – not of ranking. The problem with ranking is that we are in a society where there is a scarcity. The truly savage selection ratios that we have – one out of a thousand is actually higher than the average that we have. That means, in the jargon that you are familiar with, we are making distinctions within the 99th percentile.

When I was in IIT a few years later, I used to write recommendation letters for students who, unfortunately, after studying engineering wanted to do management in the US. And in the recommendation letters they would ask you, “Would you place the student in the top five per cent of comparable students? If not, would you place the student in the top ten per cent?” In our tradition, I see recommendation letters: “This is the most brilliant student who has ever lighted my classroom” and so on. Or, in the IIT if you get – I forget the numbers – 593 marks, you can get into Electrical Engineering in Bombay or Madras, which is prestigious. If you get 590, you can only get Mechanical engineering in Kharagpur!

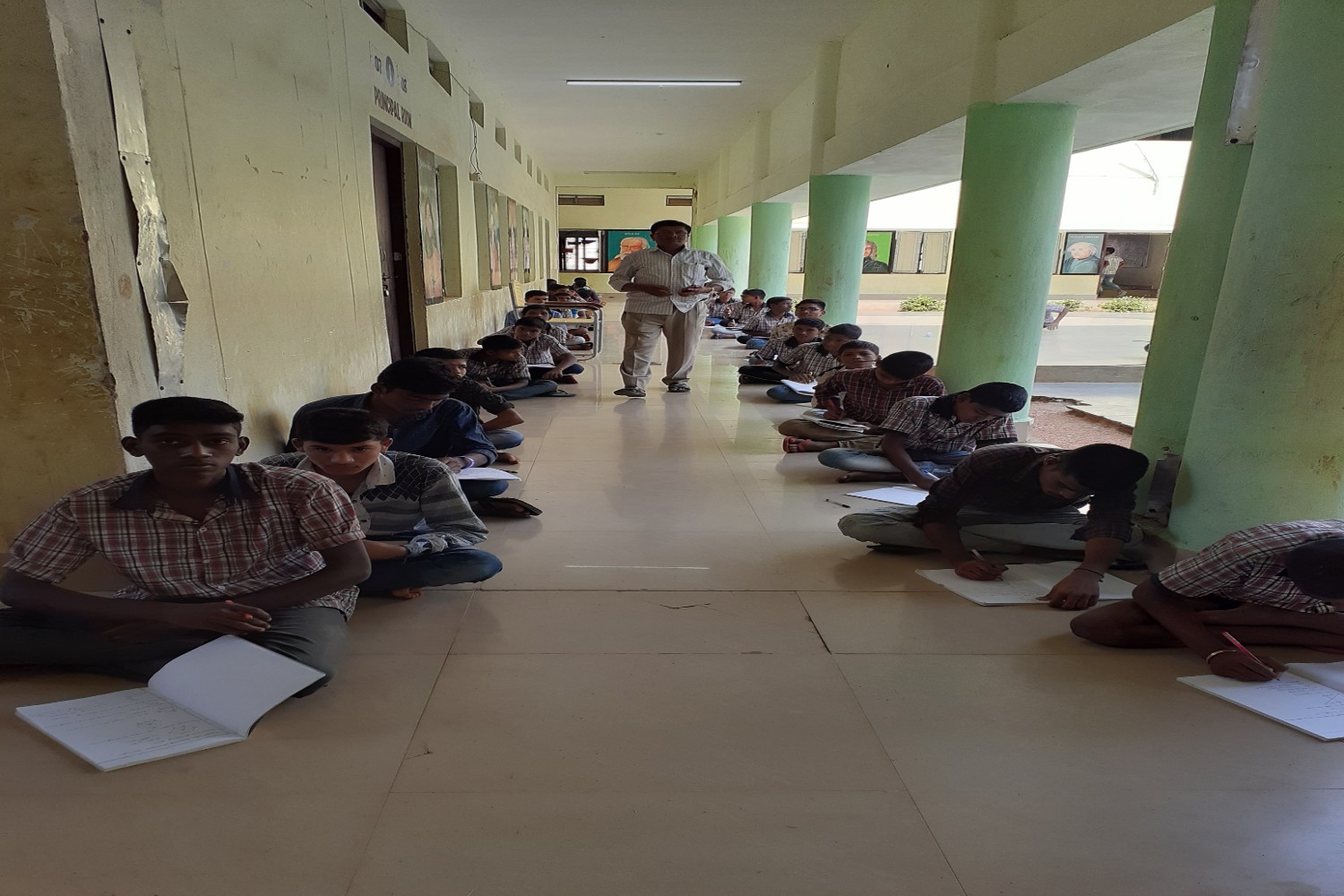

The consequence is that every exam is seen as competitive. I have worked with teachers for over 30 years. I talk about classroom testing and I say to the teachers, how do you organize a class? Their main concern is that everybody must start at the same time, they should sit apart, they shouldn’t cheat… This is an ordinary class test, and we are talking about continuous assessment. We have to help teachers unlearn this idea. It does not have to be equal treatment. Equal treatment becomes important when you have a competitive outcome – because I can’t give you three marks more and I can’t give you five minutes more, etc. This again is something that runs through our system, which I think we have to overcome – the basic assumption that if we have a test, everybody has to test at the same time.

The challenge now is that I don’t think we can work within the system and change it. We have to find some ideas from outside, and I think they are there. What are some of the things that the NCF (National Curriculum Framework) gave us? It gave us a new definition, or a new conception of the knowledge or the learning to be gained.

The exam system traditionally follows the syllabus. The structure of the question paper and the structure of the syllabus have to be exactly the same – if the syllabus has four parts, so does the question paper, and weightage is based on that. In other words, we are operating with knowledge that is static, fixed, and therefore it is predictable – which is why guide books are so useful. This is what our assessment system, or evaluation system gets at – something that is knowledge and predictable.

The NCF talks about the child being a co-constructor of knowledge. I carefully avoid the word ‘constructivism’ because a lot of people get upset with it at various points. It talks about going beyond the textbook and relating it to life outside the school. What does this mean? That the knowledge to be gained is not already determined, not already spelt out, in the syllabus. If that is what we are trying to assess, then my trade – that of testing – can be of help in illuminating and clarifying that.

I have argued that what we call Continuous Comprehensive Assessment became possible only after NCF, or the re-thinking of NCF. The CCE was mentioned in 1986, in the national policy on education. But when we had fixed knowledge to be handed over as it was and to be reproduced as it was, where was the scope for Continuous Comprehensive Assessment? Unit test plus unit test plus unit test… adding up to the total was what was required. It was logically not possible to have continuous assessment of the flexible way we are talking of.

We also say that children learn at their own pace, that we have diversity, and want to value and promote it. Then we have a context of this process of learning where assessment will claim my specialization – assessment adds something to pedagogy. I will just say this: any purposive, goal directed, autonomous activity, is actually moving in a somewhat unpredictable path. We have goals. But the whole definition of a goal, target or a destination is that I am not there now. This means that, having accepted something as a goal, we are saying that we would like to work to reach it. If that path is open-ended, then we need something called monitoring, or reflection, or analysis, to check that we are moving in the right direction. So if we say learning is open-ended, then learning won’t happen in the way we would like it to happen. We need to monitor it. I am using the word ‘monitor’ in the best sense of the term, as a way of a small cycle of feedback and so on.

This monitoring evaluation has to be autonomous, has to be local. This is really the problem in our country, in the education angle. We have to move to giving precedence and priority to the local. Continuous Comprehensive Assessment, even at the common sense level, requires this. There are no ifs and buts about it. Continuous assessment can only be done by a teacher on the fly, in the classroom.

We can come up to the gate of a school with our advice and our manuals. The rest we have to leave to the teacher if we want CCE to happen. If we want to do paper setting and make the teacher administrate in class, which we have always done, that will work very well. So the role of assessment, reflection and monitoring becomes useful to pedagogy only if it is kept autonomous. Which is why CCE has to be seen as an extension of the principle of internal assessment, but with a break.

Internal assessment, which said 15-20 marks internal and 80 marks external – I am a little more familiar with the university system – what does it mean? Even if we say that internal assessment can use other methods, can look at other qualities that the written final cannot, etc., the two things have to be added. You can’t add apples and oranges. So this also has to become an orange – internal assessment also has to be according to a scale of high and low unit differentials.

A comprehensive assessment of multiple things cannot be something that can be added. It has to be an autonomous sector on its own. So this autonomy of assessment should be in the hands of the teacher, but of course with support. We need a curricular understanding, we need sourcebooks, materials and teacher orientation. But in the actual act, we have to let go, which will be something extremely new as far as the tradition of our country is concerned.

There was an exercise undertaken in the NCERT (National Council of Educational Research and Training) called ‘Sourcebook of Assessment’. In the first round it was so heavy, it ran into 800 pages. My colleagues in the Department of Elementary Education reduced it to a manageable 100 pages or so for different subject groups. It was initially prepared for trialling. At a workshop that UNICEF funded, ten states were identified and there was this huge operation of sending these out for trialling in large numbers of schools over a period of a few months. I remember saying then that this is the first time in our lives – in the history of India, as far as I know – where a resource which has so much of wisdom going into it is being taken to the teacher, not to implement but to tell us if it works.

That is my dream. I don’t think it really happened that way because a lot of the officials who came were used to getting teachers to implement. Now, there is a whole body of experience, but I don’t think that has been recorded. What were the things that a few thousand teachers in ten states said about the workability of the system? That is what we, as a system, need to learn from them. It is that commentary that is important.

If we are going to have assessment as a part of pedagogy in order to improve, what is it that assessment telling us, which we use in order to improve? This is not a part of our culture, our whole system, of all the work that we have done on education. When you talk about moving from the small to the large, you try it out in one taluka, then you try it out in two talukas, and then it goes vertically. There is very little literature that we have of a preliminary form of using – let’s say, objective tests, or group work in classes – which we can reflect on and then say, here is a more powerful version of it.

In CCE, we have to start with something that is manageable – not this 800-page multi-dimensional form that every teacher, including those who have been recently recruited and are yet to receive induction training, is supposed to be filling for every child, three to four times a year. We know it doesn’t work. Let us start with something that is manageable and gradually extend it – not only quantitatively, but by learning. This is what assessment is. This is what the tradition of assessment is, where you see what the change is that needs to be made, what is the mid-course correction that you might want. That has to be a very rich part of our discussion.

The basic tasks for measurement – for language, for EVS – we have those. But how can we improve them to make learning more meaningful, wholesome in nature, as envisaged by NCF? This is where I have some different perspectives about the value of what is called large-scale assessment. I will take external examinations and largescale assessments in the same category because they are external. They belong to the managerial uses of assessment data – not the pedagogic uses. Pedagogic uses can only be for the teacher, or for people who are sitting down with a unit and trying to improve it by looking at answer scripts, by looking at what children say if you ask them. That is what curriculum development specialists do.

But that does not require 10,000 students. Five students of different levels of ability interacting with a unit is enough if it is going to be used for the improvement of the core pedagogic process, if you want to use it for a larger system – for deployment of teachers, teacher training, etc. But I make a distinction between pedagogic purposes and managerial purposes which are necessary. We have to certify students, select students, give some of them scholarships, put some of them into advanced classes – all this has to happen. I am not disputing that. But that is a managerial use of the technology of assessment.

For the pedagogic, we have to go back to what the dream of CCE is. The teacher can, as she goes along, observe certain children doing certain things on Monday, some other children on Tuesday, some of them while they are talking, some of them while they are working together, and gradually get a sense of where they are, how they are progressing and so on.

A last word about measurement. When you are looking at a child’s response – even if it is an essay of 15 pages, 1500 words – I don’t think you can make more than about four meaningful distinctions. I have fought the illusion that you can have 20 marks. I have worked with English teachers a great deal, and they know exactly what seven-and-ahalf marks is. When you give seven marks, what are you saying? That you know exactly what eight marks is worth, you know exactly what six marks is worth and you are sure this merits seven marks?

There are many personality dimensions that have come into the CCE formats. At the forum that the NCERT organizes, every state has this and they are on a four-point scale, a fivepoint scale and so on. What are the things about children’s sensitivity that you can put on a five-point scale? What we do we see is maybe a broad high and low. So we have to forget a lot of the measurement.

We moved from the marks system to the grading system. But we keep going back to the marks system because again there is this delusion that if it’s there and we’ve observed it, we must assign a mark to it. We have to unlearn this. We have to move into what, in measurement, we call the nominal scale, because when we use numbers 1-2-3-4-5, they are like grid numbers or room numbers. One only means ‘not two’ – not ‘better than one’. If there is a ranking then, of course, a scaling has to be done. But we need to think about qualitative categories.

Even when you are doing measurement of human qualities, qualitative categories would fall into a mark of three or two before you give a grade of A or B to somebody. You are making a qualitative distinction. You are perceiving a qualitative difference, which is coded as a mark or grade. We have always talked about these things as happening indirectly. This is where we have to focus. As children are growing and developing and learning in the new context, what are the ways in which they are changing, and which of those changes do we want to capture? Once identified, for convenience we call them satisfactory or unsatisfactory.

The external tests, survey tests with a standardized measure, have this limitation. A standardized measure can rate every child if you are a part of an amorphous mass from which we can sample. That needs to be done, but we need to be very clear about what the purposes are for which it can be done. If a child in a particular school in a rural area or in a fancy school, at a certain stage does not know the answer to a question which comes, what does that tell us? If we use a standardized measure, would it tell us something about the child, the curriculum, or the teaching?

A great deal can be done with data – the survey data, the national assessment and other things that you and I are familiar with. But they have all gone into the managerial resources, and very little into curriculum pedagogies.

You will find two propositions, two premises that we have. One is, we are saying that if you give students this sort of experience, we believe that many of them will learn what they are supposed to learn. Conventional examinations work with that system – this is in the syllabus, we have reached March and the syllabus has been covered, and therefore it is fair to test. But we are also making the assumption that this experience has been delivered.

Our examination system is being blind. So children from schools where teachers were never posted in the first place also write the exam, and they are marked by the same standard. The content validity of the educational test comes from the fact that it matches the syllabus. This runs through our thinking too – that it is appropriate to give this test to a child at this point because it is there in the syllabus. It shouldn’t happen. We need to keep asking: Has it happened? And further, we need to ask: Even if it did happen, are we sure that this is the learning that will take place? Now that we have granted unpredictability in learning, this whole business of assessment becomes very, very problematic.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!