Aligning with the state education system: the journey of Organisation for Early Literacy Promotion

Keerti Jayaram, in her essay, shows how effective partnerships can be built with the government for supporting the learning needs of children from low-literate backgrounds, especially in the context of early literacy.

This article tries to capture the experiences of Organisation for Early Literacy Promotion (OELP) as an organization, of working in alignment with the public education system, to serve the educational needs of underprivileged and underserved children. The first section discusses the evolution of our interventions in the early literacy space, and the ways in which we have tried to learn from our context to serve our communities better. The subsequent sections discuss how the unfolding of this work has been tied with the governmental school system and provides a contour of the processes of collaboration with the state.

The beginning and unfolding of OELP’s interventions in early literacy

Beginnings in the early grade classrooms of Delhi’s state-run schools: OELP was registered as a not-for-profit organization in 2008. Our work, however, began in 2006 as the Early Literacy Project (ELP) within Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) schools in Delhi’s Najafgarh Zone. ELP was conceptualized as a sustained and ongoing engagement with the mainstream education system. Its work was grounded in classrooms. It included regular interactions with teachers, school management, education officials, and other stakeholders.

The idea was to engage daily with the complexities of classrooms, learners, teachers, and contexts. This engagement was to allow conceptually sound pedagogies and classroom practices to emerge in an organic and grounded way. We also wanted the work to be aligned to the contours of the mainstream education system. The selected MCD schools catered mainly to children of migrant, daily wage workers, and others engaged in petty economic activities.

Our enthusiasm was, however, short lived. We encountered experienced teachers who were resistant, and at times threatened by our presence. We found that the prevalent rote learning practices were not effective in getting children to read. The general tendency of the teachers was to be dismissive and blame the children’s home backgrounds for their low levels of achievement. For most teachers, reading was equated with decoding the script. Their major challenge was that during vacations the children forgot all that they had learnt, and it meant going back to square one, each time.

Through our initial engagements inside the classrooms, we identified a few motivated teachers interested in exploring more efficient reading practices for young learners with us. This became our entry point. We worked with these teachers’ active involvement, inside their classrooms, to develop innovative pedagogies for meaningful decoding, and corresponding practices, which engaged the learners actively and meaningfully.

This gave a sense ownership to the teachers. Gradually, as the children began to respond positively to the new approaches, more teachers got involved. We now began to experience the power of modeling impactful classroom practices and demonstrating corresponding learner achievements. We have subsequently used these as effective strategies for influencing changes in teachers’ beliefs and practices. In fact, they have become the cornerstone of our approach.

Making sense of classroom practices, and their underlying principles of learning: In this context, we tried addressing the real needs of government teachers in terms of what they were teaching and how it was being taught. To make a difference, we must meet the learners where they are – both teachers and students.

Most early grade teachers, whom we have worked with, engage with traditional approaches to reading. This involves recitation and decoding of the Hindi Varna Mala and simple words and sentences. These processes are supposed to take place within classrooms, and are teacher directed.

To get a better understanding of the individual reading processes of young learners within these government schools, we conducted individual reading observations in Hindi of 1,300 early grade students. We were supported in this effort by 22 students from two DIETs (District Institutes of Education and Training). We arrived at the conclusion that many students from Grades 1 to 3 were struggling with decoding. Engagement with matras was a major impediment to fluent reading.

We used the above learning to rework the approach to beginning reading (decoding) using aksharas as the basic linguistic unit, as is the approach within the traditional Barakhadi (alpha-syllabic chart). Accordingly, the Hindi Varna Mala was regrouped into six (6) groups called Varna Samoohas, through trialing over two years with the active involvement of government teachers.

We then explored ways of making decoding meaningful. We enabled learners to create their own written words from their local languages. They were facilitated to do this by combining aksharas from displayed charts through a variety of game-like activities. This generated an enthusiastic response. It engaged the learners with beginning reading in meaningful ways.

A variety of games were developed for engaging learners with the displayed charts in active ways. This process resulted in much more learner-centric and active classrooms. Shifts in the learners’ active engagement with meaningful decoding gradually brought in corresponding shifts in the teachers’ beliefs, practices and motivation.

Most importantly, the learning materials, which were developed with the involvement of the government teachers, were simple. These allowed multiple usage at multiple levels. This addressed the challenge of multi-level and multi-grade situations to some extent. Therefore, it gained greater acceptance from a wider group of teacher.

Key milestones in our journey

Relocated to rural schools in Rajasthan (2008): After engaging in selected MCD schools in Delhi for two years, the extension of our work got stalled. This was due to some bureaucratic impediments. We, therefore, began to look further afield. In 2008, we obtained permission from Government of Rajasthan (GoR) to work in select rural government schools in Ajmer District. It is important to note that OELP’s interventions were relocated as a result of compulsions driven by delays, due to changes in the higher-level bureaucracy.

Development of the Field Resource Centre (FRC) in Ajmer District (2008-2015): In this phase, we tried to develop knowledge building as a core area, with a focus on Early Literacy and Learning. The FRC’s program components included demonstration classrooms for research, and developing and modeling conceptually sound and grounded high impact classroom practices and pedagogies. It also involved offline capacity building and professional interactions with other stakeholders. These included teacher education institutions, GOs, and NGOs across a wide geography.

Growing learnings as a resource organization (2014-2017): In this period, we were appointed as a resource organization for training key resource persons, master trainers and teachers by GoR. We were also invited to become members of MHRD’s Advisory Committee on Early Literacy. During this time, we also made a shift from remediation to foundation building. We were nominated as a member of NCERT’s Core Committee for developing Guidelines for the Early Years Curriculum.

Scaling up the work (2017-2020): A major part of our work during this period involved scaling up across seven (7) districts and 14,000 schools in Rajasthan, at the behest of GoR. We also worked as a member of the Core Group for drafting the National Position Paper on Early Literacy and Language Learning, initiated by Care India, USAID and Azim Premji University. We were also invited to the UNESCO Asia Summit, to present our work to representatives from approximately 40 countries from the Asia Pacific region.

Post-pandemic challenges and compulsions (2020-2024): The COVID-19 pandemic hit OELP hard. To stay afloat, we have been compelled to reinvent ourselves. There is now a greater presence in the digital space. This is because we were unable to support the onthe-ground scaling up. We had to withdraw from the districts.

We are exploring options for setting up the Ajmer Field Resource Centre as a mentoring and knowledge building site, with a focus on early learning/foundational learning. We also plan to enhance our online offerings through a digital resource centre housed within our website.

A modularized online course is also being planned. Its goal is to equip educators with conceptually sound and practical classroom practices. The strategy involves supporting high quality foundational learning, based on real-time classroom videos. It is contextualized to address learner diversity and inclusion.

The guiding principle of the course acknowledges that it is not enough to know what to teach. It is equally important to know how to facilitate high quality learning in the early grade classrooms catering to learners from diverse backgrounds.

Addressing learners’ real needs: Over the last decade and half, as a country, we have made significant progress in enrolling our children in schools. However, enrollment doesn’t ensure inclusion. OELP has tried to generate impactful classroom practices, which facilitate meaningful engagement with the mainstream curriculum, while being entrenched in sound learning principles.

Our on-the-ground practice has involved strategies that have been useful for building pathways for establishing foundations for high quality learning in young learner from low literate backgrounds. We discuss a few of these below.

Understanding the importance of recognizing learner differences along multiple dimensions has been important. We have found that classrooms within these schools are spaces which reflect the socio-cultural and linguistic diversities and the social stratifications of the larger context within which they are located.

We recognize the importance of identifying some essential elements of an enabling and conducive physical and social classroom learning environment for young learners, and the possible ways in which these could be adapted to the resource poor and low literate contexts of our work in practical and doable ways.

We have also tried to address difference in ways that has made success achievable for almost each young learner in the class. This has been essential to bring about a positive sense of self. We have tried to actively involve each learner, including those who had earlier preferred to remain as passive and mute spectators rather than risk failure.

Evolving strategies for engaging with learner diversity has also been a key part of our work. An effective strategy involves the innovative use of names and name cards through a variety of activities and games. Active engagement with name cards gives each child a sense of belonging and acceptance while creating an element of fun.

By shuffling and pulling out individual name cards, teachers have been able to ensure the active involvement of each child. These name cards have also proved to be a stimulating and engaging tool for engaging children with reading and writing, while at the same time being used as a tool for classroom management.

Creating active learning classrooms through the establishment of planned, print-based corners, and their usage in multiple ways as learning tools by teachers and learners, have also been very useful. Thus, the displayed print material on the classroom walls provides low-cost learning material. This is easily accessible. It facilitates doable ways of providing multiple teacher-directed or learner-initiated learning experiences. This helps to build a sense of ownership and autonomy in both teachers and learners.

Planned strategies for engaging with the children’s errors are essential to build up their level of confidence and create classrooms as non-threatening and cooperative spaces in which learning is a positive experience for each child.

If a child is struggling and unable to successfully engage with a task, she has the option of calling out a friend to help. Tapping into peer support has proved to be effective for creating a climate of mutual respect and cooperation within classrooms that honor learner diversity.

Working with the government for supporting the learning needs of underserved children

Addressing issues of context and marginality with rural government schools: Current literature on children in poverty has highlighted the desire of marginalized populations for formal schooling. It also foregrounds that the school, at the same time, functions as a space that is inherently disrespectful of their present life situations.

Under macro programs like Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan, we experienced large-scale initiatives being taken up by the State Education Department for building foundations in reading and writing at the levels of classes 1 and 2. Most of these initiatives were being implemented as predesigned packages.

These were located within a larger predetermined framework of Continuous Comprehensive Evaluation or CCE. These were being supported by some large-scale initiatives on reading, such as periodic “Reading Campaigns.”

Major challenges in working with the government in education, and strategies for dealing with these

Major challenges

- Ensuring program continuity and sustainability in a constantly changing and dynamic field, with frequent changes in the education bureaucracy at all levels

- Engaging effectively in multi-level and multi-grade situations

- Bringing shifts in deeply entrenched traditional practices and teachers’ beliefs

- Engaging with teachers who are grossly overburdened with non-teaching tasks

- Aligning with the changing programmatic mechanisms in the government system and the available resources

- Availability of minimal resources, for developing conducive learning environments with effective monitoring and support systems

- Addressing the specific needs of young learners from low literate homes, who have minimal support for school-based learning

Sustainable strategies

- Setting up demonstration sites for modeling high impact and doable classroom practices

- Mechanisms for building a resource pool for program mentoring and monitoring at the block and district levels

- Developing an ecosystem driven by teachers and mentors, supported with online options, for sharing best practices, and offering support

- Quarterly reporting at the state, district, block, school, and community levels

Our assessment of the context: Within the space of our limited “worm’s eye” experience, we found these centralized macro initiatives being implemented as de-contextualized, “one size fit all,” target-driven programs. These were often mismatched to the particular, and often diverse, needs of specific groups of learners and teachers. The structured and predetermined content and processes tended to be somewhat mechanical. These were also largely ineffective in bringing changes in learner engagement and achievements.

We could see the challenges of the teachers. They often feel disempowered. They are ill-equipped to deal with the specific sociocultural and linguistic needs of their learners. The teachers are also under the constant scrutiny of a target-driven system. It requires data quantification and reporting almost daily.

Matters are compounded by the social distance between the urbanized, and socially better off, government teachers and the learners. The latter are mostly from the lowest rung of the social ladder. They come from homes with minimal opportunities to actively engage with print.

Engagement at the cluster and block levels – letting the work speak: We were convinced that for any conceptually sound classroom practices to gain ground, we had to demonstrate success within these classrooms. Our intensive classroom engagements have allowed us to build deeper understanding of the learners, teachers and their contexts.

This has also allowed us to explore meaningful synergies with the curriculum and the mainstream education system. Our idea has been to align with and strengthen the system in ways that are doable, low-cost and scalable. We have not been interested in setting up a parallel system.

We began to share small successes with wider groups of teachers, and middle-level education functionaries, at the cluster, block, and district levels. This resulted in the training of teachers from 120 schools of the Silora Block in which we were working. These teachers also voluntarily acquisitioned our learning materials.

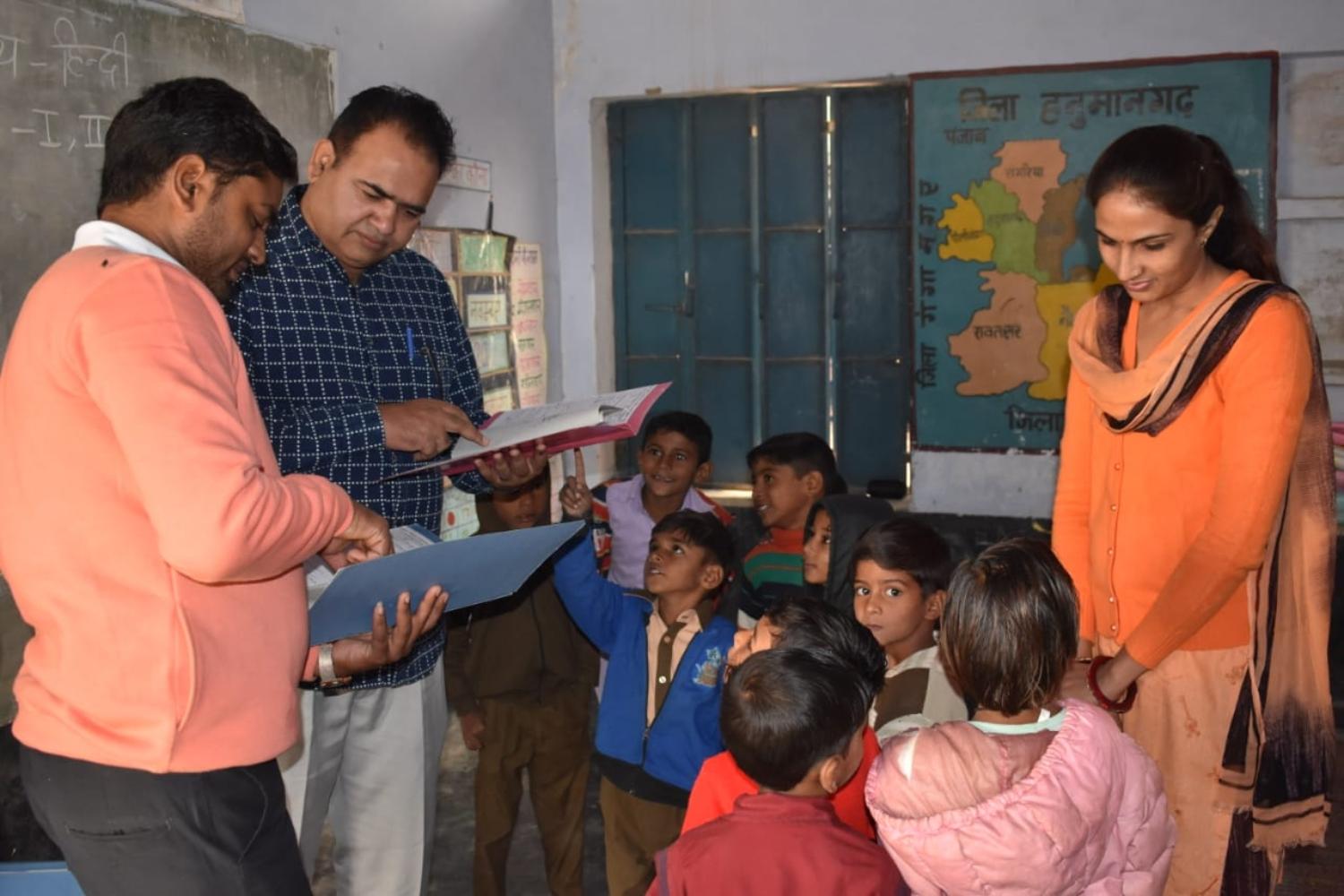

We invited district officials into classrooms to experience the shifts in learning for themselves. These interactions helped to build confidence and a sense of ownership within the teachers. They also generated a support group for OELP within the district education system.

It was important for these officials to experience learner achievements for themselves inside our classes. They could discover happy children making their own words or reading and writing each other’s names or reading poems. The officials also experienced shifts in the teachers’ attitudes toward learning and learners.

This process was important. These officials began to compare our classes with those in other schools in which we were not working. They became ambassadors for the OELP program at block and district level meetings. They began to attend monthly teachers’ meetings. We were also able to draw a pool of resource persons and mentors from amongst these middle-level education functionaries.

Small success stories began to emerge: One such story is being shared here as an example. In Sri Ganganagar, after a district level meeting, the DIET Principal showed a keen interest in the OELP program. We were able to convince him to visit three schools, along with a few DIET faculty members, to take stock of the situation.

On the 9th of October, 2018, the DIET Principal, the Vice-principal, and the OELP representatives visited three schools. These included Government Secondary Girls School at Sawatsar, Government Upper Primary School at Lalpura Odan, and Government Senior Secondary School at Ratewala.

They observed the implementation of the OELP pedagogies. They could also see the use of our resource kit inside the classrooms. They found that in the Lalpur Odan School, the teacher was active, the OELP material had been displayed, and it was being used effectively.

In the other two schools, however, the material had been partially displayed. The teachers also required support for understanding its purpose and proper implementation.

To address the needs of the teachers, the DIET Principal took the following actions after the school visits. An OELP demo room was setup in the DIET at Sri Ganganagar. This was used for displaying the OELP material, and for setting up learning corners.

This room was subsequently used for training pre-service student teachers. The room set up as a part of OELP’s interventions also became a venue for several government trainings, workshops, and regular meetings.

Assessing impact and scaling up work

Impact assessment by the government: In June 2009, OELP presented the work of the Early Literacy Project to senior Faculty members of Regional Institute of Education (RIE), Ajmer, along with district-level government officials, SSA functionaries, and representatives of NGOs. This led to an Impact Assessment Study of OELP’s Early Literacy Project (ELP).

This study was conducted as an external evaluation over a span of a year. It took place under the leadership of Professor K. B. Rath, HoD, Education, and the acting Principal of Regional Institute of Education (RIE) Ajmer.

The study included components for quantitative, as well as qualitative analysis. A presentation of the findings was made in the Academic Staff College of University of Rajasthan.

It was chaired by Professor Shantha Sinha, Chairperson NCPCR. The presentation was well attended. The audience consisted of representatives of GOs and NGOs, academics, senior members of civil society, and students.

After the impact assessment study by RIE, our work began to receive positive feedback. We could receive active support from district and block level education functionaries and SSA officials within Rajasthan’s Ajmer district.

Scaling up: After a surprise visit by senior bureaucrats to OELP’s worksites in 2015, the OELP learning materials were reproduced and distributed to 14,000 primary schools across seven (7) Special Focus Districts through costs incurred by the State. These materials were made available free of cost by us.

In 2018, Government of Rajasthan signed a four-year MoU with OELP. The goal was to support the scaling up of our education innovations in 14,000 government primary schools across seven (7) Special Focus Districts.

Implementation process: By 2022, we planned to have a scale-up model, which could be replicated widely. OELP worked with PEEO clusters (each Panchayat Cluster has approximately five schools), with one demo school to be set up in each cluster.

Digital support was also provided. This was in the form of modularized and guided digital engagement with the Mobile App content through a Trainer App. Each Trainer App housed 2–3 PEEO clusters (10 to 15 teachers), with an experienced teacher and a district/ block RP appointed as mentors.

There was an overall positive response. Some interviews with government teachers from the pilot schools may be accessed through this web link.

Reflective insights

After sharing details of our journey of collaborating with the government for making early literacy teaching learning in schools effective and equitable, I conclude with some reflections and insights drawn from this experience.

The program components have evolved through an organic process of sustained field engagement. This has helped us ensure that the program components are grounded in the complexities of the mainstream education system.

A bottom-up process of engagement has enabled us to identify and address real needs at various levels. It has also facilitated meaningful processes of building conceptually sound learning strategies by theorizing classroom practice.

These have included strategies for equipping children from diverse backgrounds for school-based learning, and addressing shifts from oracy to literacy for children from low-literate backgrounds. Addressing shifts from home language to school language and the developmental needs of young learners are crucial. So are enhancing higher order thinking for each child.

Modeling classroom practices, and demonstrating learner performance shifts, have proved to be effective strategies for building support for the program at multiple levels. Sustained engagements with various stakeholders during the project development process have enhanced the sphere of program ownership.

This process has also facilitated greater teacher agency. Teachers respond positively to classroom practices and pedagogic approaches that address their real needs in simple and doable ways.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!