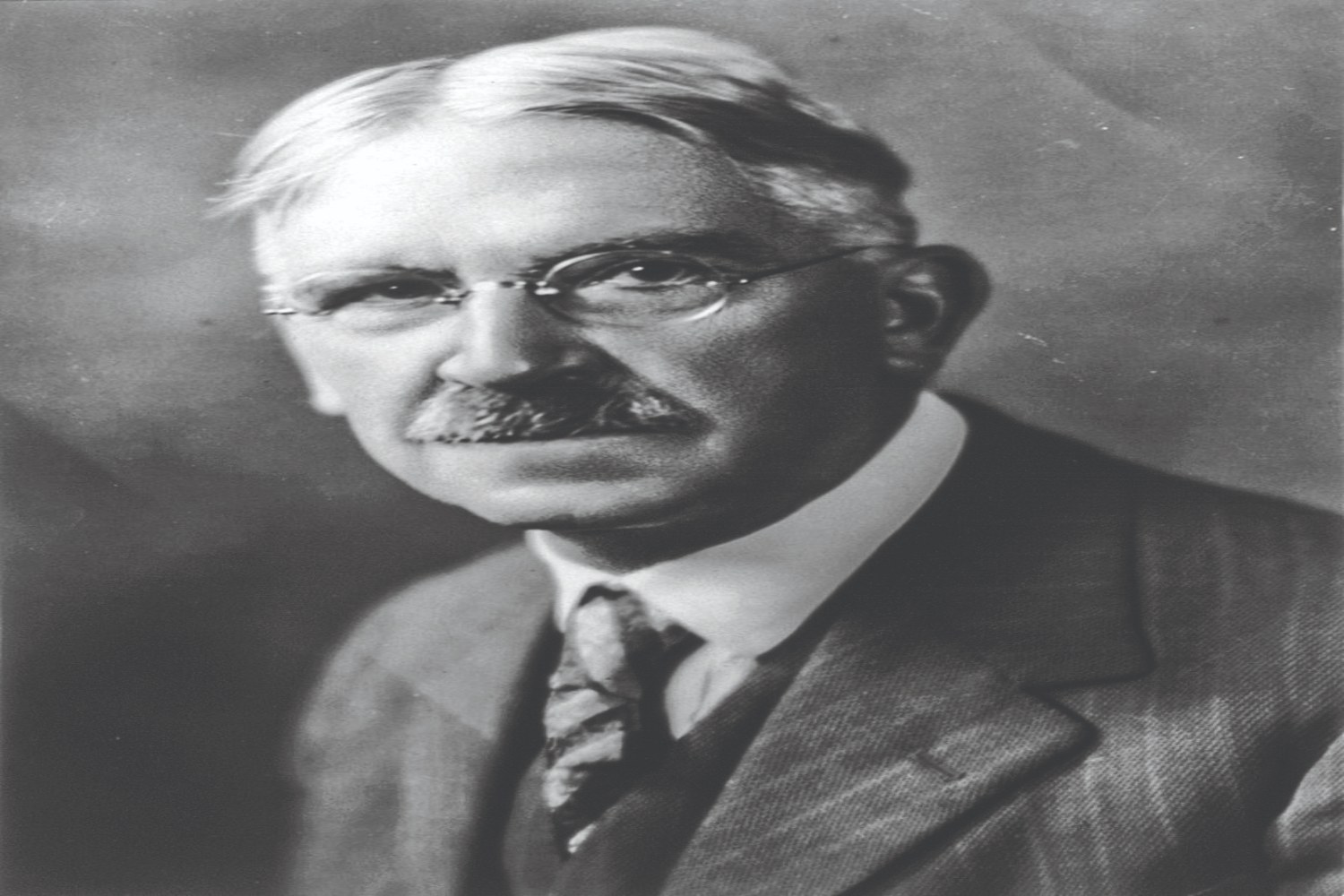

John Dewey (1859-1952), the American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer writes ‘Experience and Education’ two decades after founding the Laboratory School, at the University of Chicago. He presents a ‘Philosophy of Educative Experience’ that elaborates on the organic connection between education, and the quality of educative experience of the learner.

Dewey lays much emphasis on democratic ideals of inclusiveness, and the continuity of experience in spiraling the learner towards greater insights and knowledge.

‘Experience and Education’: A Summary of the Arguments

Chapter 1 juxtaposes ‘Traditional vs Progressive Education’. Dewey begins by laying the foundation of his argument by contrasting traditional and progressive philosophies of education. He elaborates that one cannot dismiss, the important roles of ‘past experiences’, ‘organization of content’, ‘adult supervision’ in the education of still developing minds. He cautions educationists against extremes of education philosophy, wherein ‘traditionalists’ follow the strict and the rigid, and ‘progressives’ consider the role of the above three factors as being too restrictive. He urges educationists to engage in “a positive and constructive development of purposes, methods, and subject-matter on the foundation of a theory of (educative) experience” (p.7) for its education potential.

Chapter 2 builds a rationale for ‘The Need of a Theory of Experience’. Dewey calls for an understanding of the quality of personal experience, and its potential to either ‘miseducate’ or create “experiential continuum”. The onus lies on teachers to select those experiences that create adequate impact, and bring to life future experiences by association with prior educative experiences. He points out that “to discover what is really simple and to act upon the discovery is an exceedingly difficult task.” (p.11) It is easy to slip into artificial, complex, and rigid modes of mature minds, and impose knowledge on immature young learners.

In Chapter 3, ‘Criteria of Experience’, Dewey speaks of democratic ideals as being more humane and inclusive. According to him, these should be reflected in the process of designing educational experiences. Without careful thought, the principle of continuity of experience can impede development and put the learner on a low development path.

A mature educator, alternatively, can plan for experiences that instill curiosity, initiative, and purpose – every experience being a positive learning force. Thus, the task of the educator is to sympathetically evaluate and guide the moving force of experience. Here, Dewey elaborates that experience is not only that which resides within the individual but is also the ‘interaction’ with the external world that strongly influences the young learner. This understanding of the duality of continuity and interaction in experience is not only of educational relevance but is a resource. It gives valuable direction on how to design and guide relevant experiences without imposition.

Chapter 4 discusses ‘Social Control’. Dewey states that there is always some form of control within all communities. But the rules and principles formed are supposed to be for the greater good of all the members of the community. Thus, we understand that non-coercive social control is a possibility. Educative experiences can be flexible to accommodate individuality of experience. Yet these can move the group collectively forward towards more powerful learning experiences as well. It is also the role of the most mature member of a school community – the educator – to be responsible for quality and conduct of interactions and communications. In this process, attitudes and habits may be formed that promote future learning, through communications within and beyond one’s community.

Chapter 5 throws light on ‘The Nature of Freedom’. Critical of the rigid, straightjacketing methods used in traditional schools, Dewey says external limitations restrict the internal freedoms – of thought, desire, and purpose. Internal and external freedoms are interconnected. Passivity and receptivity are detrimental to intellectual activity. A freedom that is desirable then is freedom which has the “power to frame purposes, to judge wisely, to evaluate desires … to carry chosen ends into operation.” (p. 27) Stopping to think and reflect, and gradually developing self-control is the pragmatic face of freedom, for the individual, and is an ideal aim of education.

In Chapter 6 ‘The Meaning of Purpose’ is discussed. In this chapter, Dewey extends the concept of freedom – for an individual or an organization – to the process of formation of purposes and the means to execute these. For him this exercise in freedom is critical to progressive education. In contrast, a slave is one who either fulfills purposes designed by another or is dictated by one’s own blind desires. Mere action on impulse cannot be the purpose of education. Powerful purposes for education are created involving the learner in the planning of educative experiences.

‘Experience and Education’ is essential reading for an aspiring educator – not only for its unique conceptualization of the continuum of educative experiences but also for illustrating these ideas for the reader to make it explicit for practice.

Chapter 7 delves into the ‘Progressive Organization of Subject Matter’. Dewey states that the necessity and challenge for the educator lies in creating an experience continuum. Ability to carefully present new problems is necessary. So, is the capacity to extend and elaborate understanding by connecting subsequent learning experiences. Using a scientific process to bridge an understanding of past knowledge helps learners engage productively with his future and thrive. It must also lead to greater sophistication in articulation and analysis, thus connecting learning in a spiral fashion.

In this way, learning becomes seamless, allowing the learner to inch forward towards discovering the knowledge that the mature educator knows. Further, Dewey states that education must engage with both scientific and social applications of science. This leads to an understanding of the production and distribution of services and products and the social and economic barriers that humans maintain. Thus, learning experiences must necessarily use ‘critical pedagogy’ for an understanding of the self within society.

In Chapter 8, titled ‘Experience – The Means and Goal of Education’, Dewey concludes that with an ever-present dissatisfaction of the educational situation, seeing education as rooted in the personal experiences of the learner is useful.

He admits that he has not attempted an exhaustive philosophy of its principles. Rather, he has tried to expand on necessary, not sufficient conditions, that can allow educators to embark on an idea that may lead to something “worthy of the name education” (p. 40) He steers clear of adopting an ‘ism’ in naming his propositions and hopes for all to engage in their own inquiry to understand what education is – without the need for sloganeering.

Understanding Contemporary India with ‘Experience and Education’

‘Experience and Education’, steeped in the idea of understanding learner experiences and its connectedness to furthering learning, has transformative potential. It allows for connecting the learners from where they are (in their experience) to where they need to be (in a structured curriculum). If an educator can recognize that learners have unique prior learning experiences, then she may become adaptable and nimble in finding solutions for learning. Here we see how progressive thought within a traditional system merges seamlessly to create a meaningful learning cycle for students. On the other hand, many ‘miseducative’ experiences create school dropouts.

Dewey lays much emphasis on democratic ideals of inclusiveness, and the continuity of experience in spiraling the learner towards greater insights and knowledge. The problem that arises in the current scenario of school closures during the pandemic, is of undemocratic practice. Most children have no access to learning – in denial of learning continuity – while students of private schools who can ‘afford’ it, have access to this continuity.

What is the effect of this exclusionary practice, leading to learning discontinuities? How do young learners experience such an exclusionary society? How do these exclusionary policies impact learning and the country as a whole? These are serious concerns for deliberation for educators and policy makers today. While formal learning has discontinued, social learning experiences continue. For many learners it certainly has been a ‘miseducative’ one.

It is in answer to these deliberations that community-based interventions by teachers and organizations have provided for continuity of learning experiences, to the best of their abilities, across the country. These have tried to restore in a few young learning minds trust in the society they belong to.

Dewey’s simplistic assumption of a flat community structure does not hold good in the Indian context, where hierarchy is the societal norm.

Reassessing Dewey’s Ideas as a Guide to Practice

Dewey’s simplistic assumption of a flat community structure does not hold good in the Indian context, where hierarchy is the societal norm. Maintenance of power structures is how caste and class operate; the former perhaps being more rigid. Similar is the situation in bureaucratic organizations of which the traditional and public schools are perfect examples.

However, Dewey’s idea of a democratic form of social control in classrooms, and even at the school level, has intrinsic value. These are meant to be centers of societal transformation. Herein lies the critical role of the mature educator who creates inclusive learning experiences of social control towards the good of all in the classroom.

Dewey warns that this is not an easy task and slipping into traditional rigid ways are easier. As the founder of the Laboratory School, he saw many of his original ideas transformed into a more structured practice. The idea of an open, problem-based curriculum is potentially transformative.

‘Experience and Education’, steeped in the idea of understanding learner experiences and its connectedness to furthering learning, has transformative potential.

But pragmatically it requires highly qualified, experienced teachers guided by experts. These teachers then should be able to steer through this experimental research for designing an ever-changing, socially inclusive curriculum that propels learners forward towards a truly educative experience.

In Conclusion

‘Experience and Education’ is essential reading for an aspiring educator – not only for its unique conceptualization of the continuum of educative experiences but also for illustrating these ideas for the reader to make it explicit for practice. In organizational and pedagogic terms, the mature educator must be part of the community of learners, autonomous, and possess self-control. “Through a process of critical, social intelligence” (p. 31) an educator actively shapes experiences rooted in the learners’ past experiences such that learning is extended as an experience continuum into the future.

The book has important insights for teacher educators and capacity building organizations, and for teacher education policy as well. Translated into practice in the teacher education space, Dewey’s ideas could help those aspiring to become educators of mature adults gain insights into the philosophy of educative experience. By critically engaging with these ideas and insights, educators can develop into observant and responsive members of learning communities. They can, thus, train themselves to be deliberative in critically reconstructing and expanding the educative experiences for their learners.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!