Building strong foundations – The journey of early childhood education in India

This issue focuses on the theme of Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE). It has been guest edited by our Kolkata-based partner organization, Vikramshila Education Resource Society. The pieces in this issue make the overall case for the importance of ECCE as an educational sub-domain and as an area of societal concern.

Evolving conceptualizations of early childhood education

The concept of early childhood education has been shaped by the evolving notion of childhood in modern times. Earlier childhood was not considered as a distinct stage of development with its own needs and characteristics, but only as a miniature version of adulthood. It was Rousseau who first spoke of the need of allowing children to develop naturally, and free from the interference of adults. Johann Pestalozzi, an educator in the early 19th century, emphasized the importance of creating safe and nurturing environments for children, where they should be allowed to learn at their own pace. He also spoke about the importance of play.

In the early 20th century, early childhood education was greatly influenced by the psychological theories of child development and growth. Later, sociologists like Emile Durkheim brought in the concept of plurality of childhoods and spoke of how childhood was experienced differently in different cultures across space and time. The concepts of childhood, how children learn, and how learning happens, are still evolving, and the recent findings of brain research around all of these have largely shaped the discourse on early childhood education in our times.

Pre-primary education in India

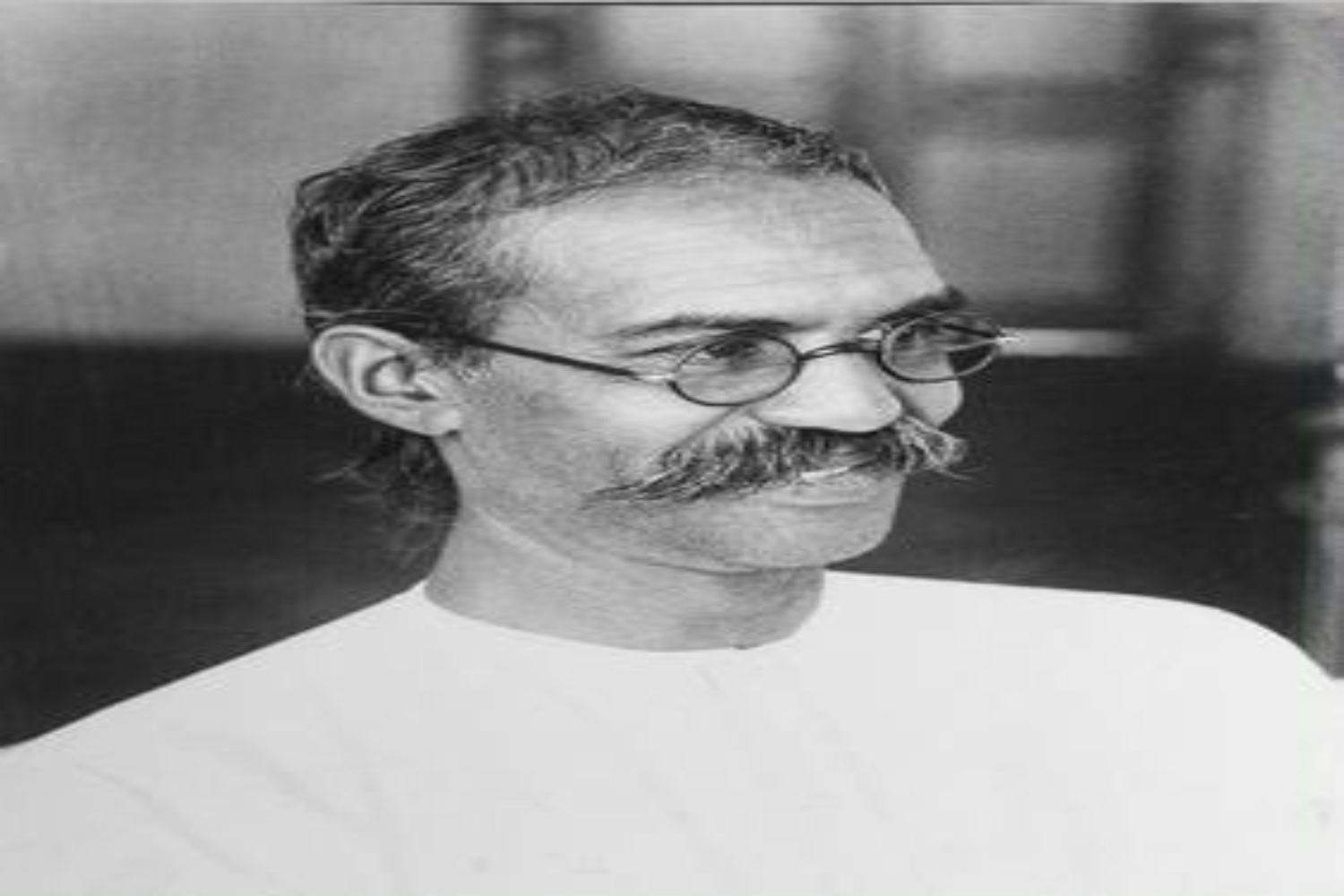

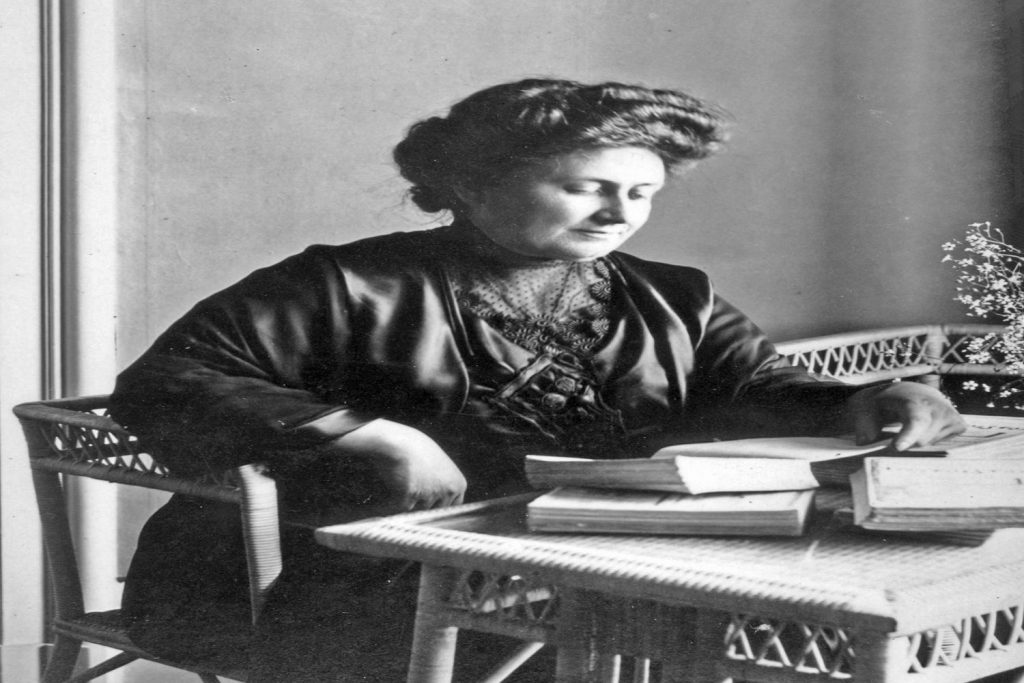

Maria Montessori, one of the pioneer educationists in the previous century, had a significant influence in the spread of early childhood education in India during the Second World War years, when she spent about 10 years in the country, touring and offering courses to aspiring teachers in different parts of India. Her method of education had captivated the imagination of leading educationists in India such as Gijubhai Vadkeka, Tarabai Modak and Sarla Devi Sarabhai.

There are references of Gandhi visiting a Montessori School in Saurashtra as early as 1915. Gijubhai started his Dakshinamurti Balmandir in 1920 in Bhavnager and later Tarabai Modak started her Shishu Vihar in Mumbai. A training course was started by her in 1938 to make up for the dearth of trained teachers needed to impart this kind of scientific education to children.

The educational theory of Montessori, based on the idea of freedom, self-reliance, care for the environment, and the importance of love to ignite the human spirit, found a resonance with several enlightened minds of those days, when the nationalist movement was just gaining momentum, and people were on the quest for a system of education that would serve as a key to train the young along these lines. Vivekananda, Tagore, Gandhi and Aurobindo were all in search of an alternative method more in harmony with Indian ideals and integrated to nature without any barriers between teachers and students, and based on the principles of love and mutual respect.

The Theosophical Society in Madras served as a base from where Montessori’s ideas spread far and wide. Students from different parts of the Indian sub-continent went there to get trained by the great educator who taught them to look upon the child as a collaborator in the process of learning. It was almost like a movement that spread gently in different parts of India, reaching out to different segments of society. Although its reach was limited, its significance was acknowledged by the Government of India, who in their report on education (1951) mentioned the role played by Montessori and her students in triggering the expansion of pre-primary education in the country in the 1940s.

Spread of pre-primary education through Anganwadi centres

Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), a flagship program of the Indian government, was launched on October 2, 1975, as a pilot in 33 Community Development Blocks, to primarily improve the nutritional and health status of children in the country. The project was evaluated in 1979, and based on the positive results, it was extended to cover the entire country in a phased manner.

Over the years, the scope of the ICDS program has expanded to cover a wide range of services, including pre-school education for children in the 3 to 6 years age group. Today, ICDS is the largest integrated child development scheme in the world, covering over 14 lakh Anganwadi centres.

The program has played a significant role in promoting early childhood education among the rural population. Today, preprimary education in India includes a variety of programs, such as Anganwadi centres, nursery schools, playgroups and kindergarten chains run by private entities.

Although there is a clear policy mandate about early childhood education pedagogy, there is a wide variation in the quality of pre-primary education in India, as the private sector is largely unregulated. Both NEP and NCF have articulated the principles, methods and practices to be used in the care and education of young children,

Key principles of ECE pedagogy as per NEP 2020 and NCF 2022

The national policy documents clearly mention that ECE classrooms should facilitate play-based learning. These envisage children being given the scope to explore, discover and experiment, led by their natural curiosity and desire to learn. The pedagogy is envisioned to be child-centred and is supposed to cater to the holistic development of children across all aspects of development. These include the five domains of physical, language, cognitive, social emotional and aesthetic.

Teachers are expected by the national policy documents to be responsive to the needs and interests of young children and build positive relationships with them and their families. They are also supposed to create a supportive and nurturing learning environment. All these principles and suggested methods of teaching are informed by the latest research in brain development and best practices around the world.

Role of play in children’s learning

Froebel, Pestalozzi, Montessori and Dewey were pioneers in the field of child education and all of them believed that the child’s own instincts, activities and interests should be the starting point of education. They spoke about the importance of play and exploration as the child’s natural way of learning. With the emerging concepts of childhood, the ideas around child-centric education got more crystalized. Scholars and educationists like Piaget, Bruner, Vygotsky and Gardner have further strengthened these ideas. According to them, children construct their own knowledge by assimilating new experiences with their existing knowledge.

Vygotsky spoke of how the active engagement of children with other more experienced and knowledgeable persons results in expanding their learning. Bruner highlighted the importance of a spiral curriculum in multi-age/mixed group settings, where the same set of topics are taught to a child at graduating levels of difficulty for a full three year period through different experiences.

The dichotomy between play and learning in India

Although these progressive ideas around play as children’s way of learning are widely accepted by educationists, there exists a latent undercurrent of resistance. There are many who think play and learning to be mutually incompatible. While educational thinkers talk of play as the child’s way of learning, there are many who feel that play is a ‘waste of time.’

Attitudes towards play are shaped by social pedagogy traditions that are well-entrenched. Sustained exposure to a different way of thinking is needed to change mindsets. It is generally found that most European countries are more accepting of a holistic learning framework based on care, play and development of social-emotional competencies. Whereas, in Asian countries there seems to be a greater emphasis on school readiness and direct instruction even in the preschool years.

Context plays a role in shaping attitudes, beliefs and perceptions of teachers too, who have the responsibility of implementing play-based learning in their classrooms. Prevalent among many teachers is a dichotomy between the role of child-led, child-initiated, free play activities, versus a teacher-led instruction-based play activities.

Most teachers believe that while free play is very good for developing social-emotional skills and communication skills, direct forms of instruction are needed for children to learn the basics of literacy and numeracy and other forms of more ‘academic’ learning. This belief also influences how much freedom a teacher will accord to children to manage their learning or whether at all any autonomy is to be given to them.

The other problem that is not much talked about while discussing the pros and cons of play-based learning is the need for an appropriate environment equipped with adequate play materials to facilitate play-based learning. Further, teachers who are expected to implement a play-based curriculum lack the requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes to scaffold children’s learning, while allowing them to follow their instincts, interests and abilities.

Some of the ambivalence, doubt and uncertainty that we find in teachers today around play-based learning is also due to their lack of confidence in implementing a play-based pedagogy. Teachers feel that there is a contradiction between the principles of pedagogy laid down in policy documents and administrative expectations at the systemic level focussing on learning outcomes. The attitudes and beliefs of parents, too, put pressure on teachers as they are more focussed on academic learning and reluctant to accept the value of play.

Dichotomy around giving agency and freedom to the child

There is an interesting anecdote about a visitor to a Montessori school, who found the children busily engaged in different activities, talking freely to one another whereas the teacher’s presence was hardly noticeable. Slightly disconcerted, the visitor asked one five-year-old girl ‘so in your school you can do what you like,’ to which the girl in all earnestness replied, ‘No ma’am, here we like what we do’.

This small but significant encounter offers a very interesting insight into the idea of children taking charge of their learning, although it is a viewpoint that has been widely propagated by education thinkers all over the world. Thinkers like Vivekananda, Tagore, Aurobindo and Krishnamurthy, all endorsed a liberating view of education, where play and freedom are central to realizing the inner potential of a child.

Perhaps the urge of a captive nation striving to break free from the chains of foreign rule found resonance in education methods that accorded the learners the agency to explore, choose and take charge of their own learning. Such progressive educational ideas captured the imagination of the nation. Several high quality early childhood learning centers and schools were established in India in the previous century.

Today the scenario has changed with the emergence of a market economy that encourages competition and high scores. Although there are some lasting legacies of these great enterprises, and some preschool programs offered by NGOs and private philanthropies are of excellent quality, there has been a gradual formalization of preschool education all over. Even Tagore’s own beloved school at Santiniketan has not been fully able to stick to his principle of giving abundant joy and freedom to children while being educated in the lap of nature.

The journey ahead

But all is not bleak. There are things that give us reason to be more optimistic and hopeful. NEP 2020 and NCF 2022 have both clearly mandated that the play-based pedagogy of early childhood education should travel upward. These documents recommend play-based pedagogy to be continued in the first two years of primary education. Thus, the trend of downward percolation of formal teaching to the pre-primary classes is sought to be reversed.

The policy directive has the potential to resolve the existing dichotomy. But it is only the first step and there is a long road ahead. Teachers would need intensive, recurrent and hands-on training to internalize the principles of play-based pedagogy. Other players in the educational ecosystem will also have to be trained to develop an understanding of the importance of play-based pedagogy and helped to overcome their own personal biases or prejudices.

Early childhood centres should be equipped with adequate and appropriate play materials. And parents have to be educated and made aware. It is an uphill task but not an impossible one, as we are blessed with a rich tradition of quality early childhood education, from which we can draw and take inspiration from.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!