How is history done? A model as ‘Ready Reckoner’?

The piece by Anil Sethi puts forth the argument that the craft of the historian must inform classroom pedagogy in history. To aid such an endeavor, he sets forth a model comprising of six elements that try to tie up history writing and pedagogy together.

My aim in this piece is to introduce History and Education professionals, including school and college teachers, to a model that explains how History is done. By ‘done’ I mean how it is researched, constructed (in and through monographs, learned articles, textbooks and other materials), and also how it is taught and learnt, rather how we ought to undertake all these activities. A model is an intellectual template that ‘simplifies reality in order to emphasise the recurrent, the general and the typical.’

Identifying or formulating interesting problems for analysis will immediately bring to our work both clarity and sophistication.

I shall, therefore, present how histories are written, what is it that historians usually do, and how History as a discipline ought to be taught and learnt. By definition, a model should be generally applicable, hence mine will apply to the creation and teaching of any history, whatever its time-period, locale or theme. Furthermore, this model will also implicitly underscore the idea that history pedagogy should be closely related to the historian’s craft.

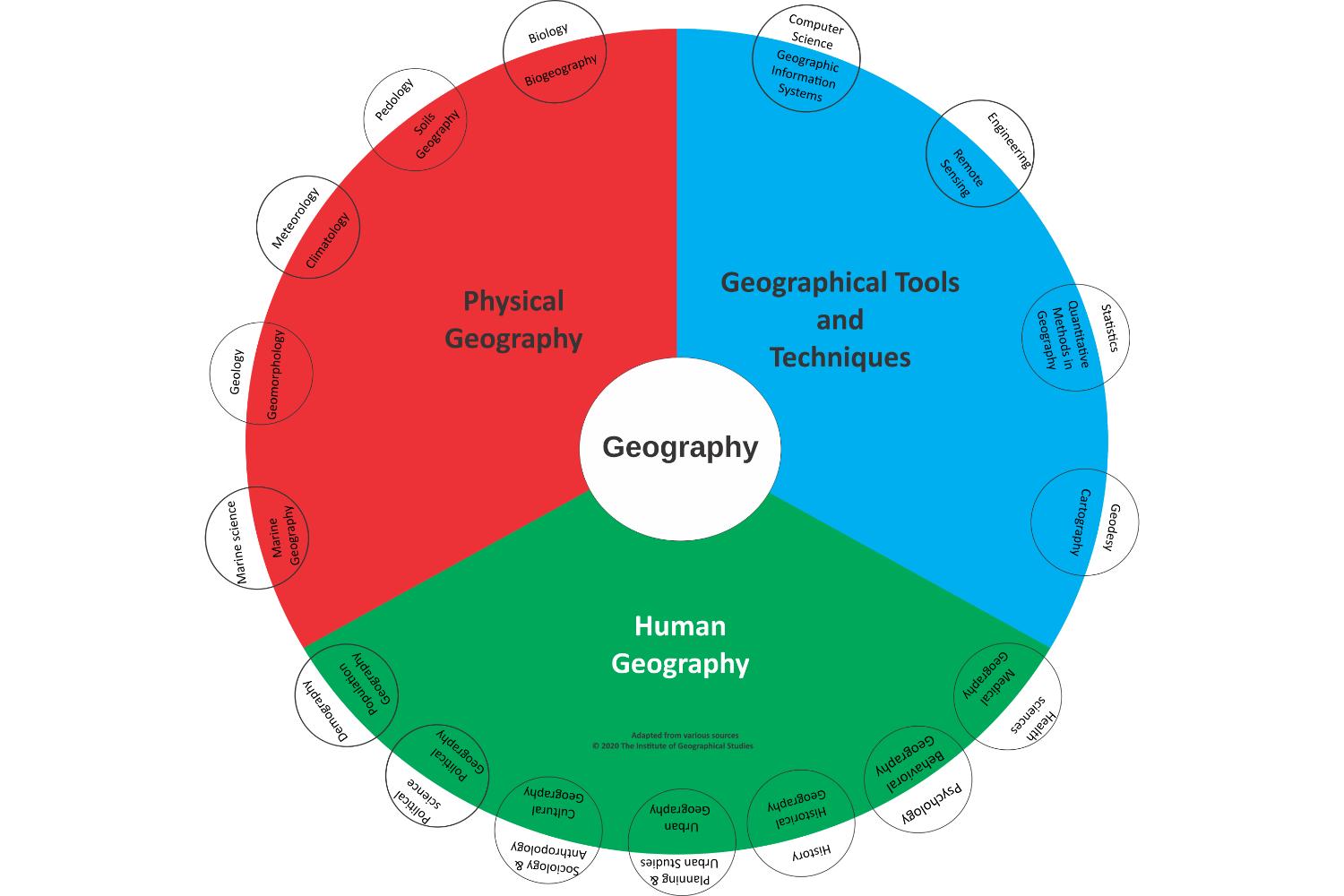

I developed this model for the purposes of teaching a course on ‘History and Social Science Education’ at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. My students in that course came from a wide range of social backgrounds and disciplines. How was I to explain the fundamentals of the best history-writing and history pedagogy to this heterogenous group of dentists, biologists, mathematicians, engineers, geographers, sociologists, literary critics and the like? I had to devise content and pedagogy that ought to go to the heart of the matter, be lucid yet sophisticated, and use not an inordinate amount of time. This model was my answer. It consists of a series of elements or steps; albeit, these do not occur in a scholar’s or teacher’s work in any linear fashion. These elements constitute the following.

- Problem(s) for Analysis.

- Explanation: Arguments and Narrative. How do arguments and narratives fold into each other?

- The facts of the case.

- Evidence and sources.

- Perspective:

- Perspective and prejudice; prejudiced perspectives.

- Interpretations from one angle of vision, from a given vantage-point; are all perspectives partial?

- Multi-vocality or heteroglossia. Many different voices: In the evidence itself; at the level of the protagonists; among scholars, that is, among historians/ social scientists. Synthesize perspectives wherever possible.

Problems for Analysis In all disciplines researchers work with analytical questions. What precisely is being investigated or analysed? In my experience, it is useful to teach and study in a similar manner, to clearly signpost the problem for analysis, something rarely done by history teachers and students. Identifying or formulating interesting problems for analysis will immediately bring to our work both clarity and sophistication.

If the chosen problem is weighty enough, it will inspire us to discover or create rich explanations for the given phenomenon, explanations that seek to grasp the interplay of a large number of factors. In order to explain this point, let me offer the following as random illustrations of some engrossing problems for analysis from Indian history.

- All of us know that, from 1919-20 onwards, the anti-colonial Indian national movement gradually became an all-India mass movement. Why did this happen from 1919-20 onwards, why not earlier or later? (In some sense, this is a quintessential history question, its generic form being: why do things happen, when in fact they happen?)

- How and when did Sikhism crystalize into a separate faith, as a religion in its own right?

- Why did Buddhism have a meteoric rise and fall in India?

- Despite the recommendations of the National Education Commission of 1964-66 (the so-called Kothari Commission), that a common public education system be introduced in the country, this never happened. Why?

- How did social class, caste, religious identity, and patriarchy interpenetrate in different time-periods and locations to produce groups suffering from what has been called compounded disadvantage? (This is a vast question. Keeping the historical contexts in focus, it will have to be broken up into several specific questions.)

Explanations, evidence and facts

Whatever be the answers to these questions, the explanations will inevitably consist of a series of arguments or narratives. From time to time, the idea of merely narrativizing events or of telling stories has been attacked and scholars have spoken about the need to discover underlying structures. Even so, narrative, in a fairly strong sense of that term, has made several comebacks in the discipline.

In the best histories, reasoning in the form of argumentation has usually come interfused with storytelling and description. But what are the historian’s arguments and narratives based on? Like the journalist and the lawyer, the historian must deal with the ‘facts of the case’ and these are culled from evidence, which in turn is gathered from a range of sources. Historians tend to distinguish between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ sources, the former being defined as those originating from the time-period of the events under investigation. It goes without saying that a critical scrutiny of the facts, evidence and sources must always be carried out.

Much can be said about ‘facts’, ‘evidence’ and ‘sources’. But owing to space constraints, I confine myself here to a few basic remarks about the training historians might receive in interpreting their evidence. All researchers must ask, how exactly a given body of evidence was created. Who created it? What exactly was created? How, when, where, why?

Remember Rudyard Kipling’s ‘six honest serving men?’ [“I Keep Six Honest Serving Men, (They taught me all I knew) …”] Kipling’s seventh ‘slave’ may well have been ‘for whom’; that is, for whom was the evidence created? Did the recorder produce the document for personal use, for one or more individuals or for a large readership? Is it first-hand evidence or hearsay? Was it meant to be used privately or publicly? Does it offer information or an argument or a perspective? In short, the historian is trained to raise a thousand questions regarding the many different formations of Kipling’s ‘honest serving men’ – permutations, if you like – and it is these questions that help us assess the evidence for its veracity.

In the best histories, reasoning in the form of argumentation has usually come interfused with storytelling and description.

It shall take many words to delve deeper into the question of evidence or write about the role of facts in historical construction. We would have to leave that for another occasion.

The problem of perspective

Arguments are formed through a critical reading of the available sources, by asking questions of them, and by stringing evidence, facts and reasoning together. The power of arguments rests on how persuasively this is done. But surely no argument or story is without perspective. Even evidence and facts are marshalled from a certain perspective.

In fact, perspective inheres in every fact or piece of evidence. Likewise, evidence and fact may be seen from different perspectives, from different angles of vision. Allow me to dwell at some length on the vexatious issue of perspective, and its role in historical (and social-scientific) constructions.

First, I wish to emphasize that not all perspectives are prejudiced. There is a difference between prejudice (or bias) on the one hand and perspective on the other. On the matter of prejudice, I can do no better than quote Bernard Lewis (History: Remembered, Recovered, Invented, New York, Touchstone, 1975, p. 54): The essential and distinctive feature of scholarly research is, or should be, that it is not directed to predetermined results. The historian does not set out to prove a thesis, or select material to establish some point, but follows the evidence where it leads. No human being is free from human failings, among them loyalties and prejudices which may colour his perception and presentation of history. The essence of the critical scholarly historian [emphasis mine] is that he is aware of this fact, and instead of indulging his prejudices seeks to identify and correct them.

Here Lewis defines prejudice for us and suggests how professionals might engage with it. While some perspectives may be prejudiced, not all are. A perspective is an angle of vision, a vantage point. Many vantage points may just be different from each other rather than being prejudiced.

Take, for instance, the issue of the Partition of British India. In writing comprehensively about this topic, so many perspectives have to be kept in mind: of the major political parties and nations of course, but also of people of different backgrounds – of the young man who lay hidden among the dead before he could run for his life from Jammu to Sialkot; of the woman performing backbreaking road repairs on a highway in eastern India; of the trader who sold wheat at wholesale prices in the retail market, eking out a living by making a few paise by selling the gunny bags in which the wheat came; of the women who were persuaded by the menfolk in their families to ‘protect’ ‘community honour’ by jumping into wells in order to commit mass suicide; and, of couples of mixed backgrounds who ran away from hospitals to god-forsaken trenches to give birth to their children.

So many stories, so many protagonists, so many voices. Do our accounts of 1947 and the names we use for it pay heed to all these voices? Was this really a ‘Partition’, a more or less agreed upon division of assets and territories; or was it a ‘disturbance’, ‘tumult’ and genocide? Or a civil war that raged for sixteen months? Why don’t we call it, ‘the creation of Pakistan?’ Why didn’t the historians’ histories speak of Partition’s untold brutality and violence until the mid1990s? When did Partition begin and when did it end? So many questions! Varied ways of looking at a phenomenon yield different questions, let alone different answers.

A perspective is an angle of vision, a vantage point. Many vantage points may just be different from each other rather than being prejudiced.

This tells us that events and social processes, historical as well as contemporary, have multi-layered and overlapping histories. There just cannot be a single way of comprehending them. They may be amenable to different narratives, created from different pivots or vantage points. It is the duty of the historian to try to create a conversation between different perspectives, to capture conflicting voices.

Such an exercise would help reveal the pluralities of a given history, of the many different pasts that have informed our realities as they emerge from the tunnel of bygone ages into the present. That is why the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) chose to name its history textbooks for Classes 6, 7 and 8 – in current use – Our Pasts. The emphasis on the plural must not be ignored.

And that is why a leading historian of our times, Peter Burke urges his peers to interpret conflicts through a conflict of interpretations. This because history is not something fixed, objective, based only on facts. In the early twentieth century, historians used to speak of the ‘Voice of History’, much as popular Mumbai film industry movies sometimes still do. Is there a ‘Voice of History’ and should uncovering this be the historian’s ideal? Or are there many varied, even opposed voices in history? Shouldn’t our ideal then be to grasp history’s heteroglossia – that is, its varied and sometimes opposed voices?

Arguments are formed through a critical reading of the available sources, by asking questions of them, and by stringing evidence, facts and reasoning together. The power of arguments rests on how persuasively this is done.

It is the business of the historian or the teacher to look at all the angles of vision bearing upon a history (or social-scientific) problem, and to establish the extent to which these perspectives are grounded in evidence and fact. This will help us assess the validity of the arguments arising from each perspective. Finally, with respect to several cases, there may be scope to synthesize arguments and perspectives; this should be done wherever possible.

Concepts and categories

Last but not the least, practitioners in the Humanities and Social Sciences use and create a vast range of concepts and categories – for ordering reality, for distinguishing between phenomena, cognate or otherwise, for generating clarity. They ought to understand these concepts and categories correctly. How, for instance, can I argue with anybody about the merits or demerits of capitalism unless my interlocutor and I arrive at a technically sound and mutually acceptable understanding of what is capitalism? How do I decide upon the character of the 1857 movement unless my fellow-debaters and I know the meanings of categories such as ‘mutiny’, ‘rebellion’, ‘war of independence’ or even ‘revolution’?

It is cognate concepts that are the most confounding. Should ‘patriotism’ and ‘nationalism’, ‘homeland’ and ‘nation’ be distinguished from each other, and if so, how? Are ‘frontier’ and ‘border’ much the same thing? Wouldn’t we feel muddled if we thought of the ‘incidence of disease’ as its ‘prevalence’? Shouldn’t we be conversant with the entire range of meanings of words like ‘popular’ and ‘populist’ before we speak of ‘popular revolts’ or ‘popular leaders’ or ‘leaders not so popular but populist’? In other words, a sound grasp of the relevant concepts and categories becomes essential for the description, analysis and narrativization of history.

Take-away

The six elements of the model which I have outlined for you here inevitably characterize all history-writing and history-teaching. It would help to be actively aware of this. This model could be used to cross-check our work and reflect on it. These six elements are the fundamental building blocks of our endeavors.

I would go to the extent of saying that the fundamental building blocks here can only be just six–no less, no more. All other artefacts, ideas, factors that enter our historical (and social-scientific) constructions would have to be subsets of these basic elements. Consequently, they would be subsumed under one or more of these six.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!