Imagining the implementation of FLN mission: creating viable models of practice on ground

Atanu Sain and Namrata Ghosh discuss how the NEP is trying to respond to the needs of very young learners through a clear focus on Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN); they also share the challenges they have faced and the learnings they have gathered through working with various governments and communities in this space.

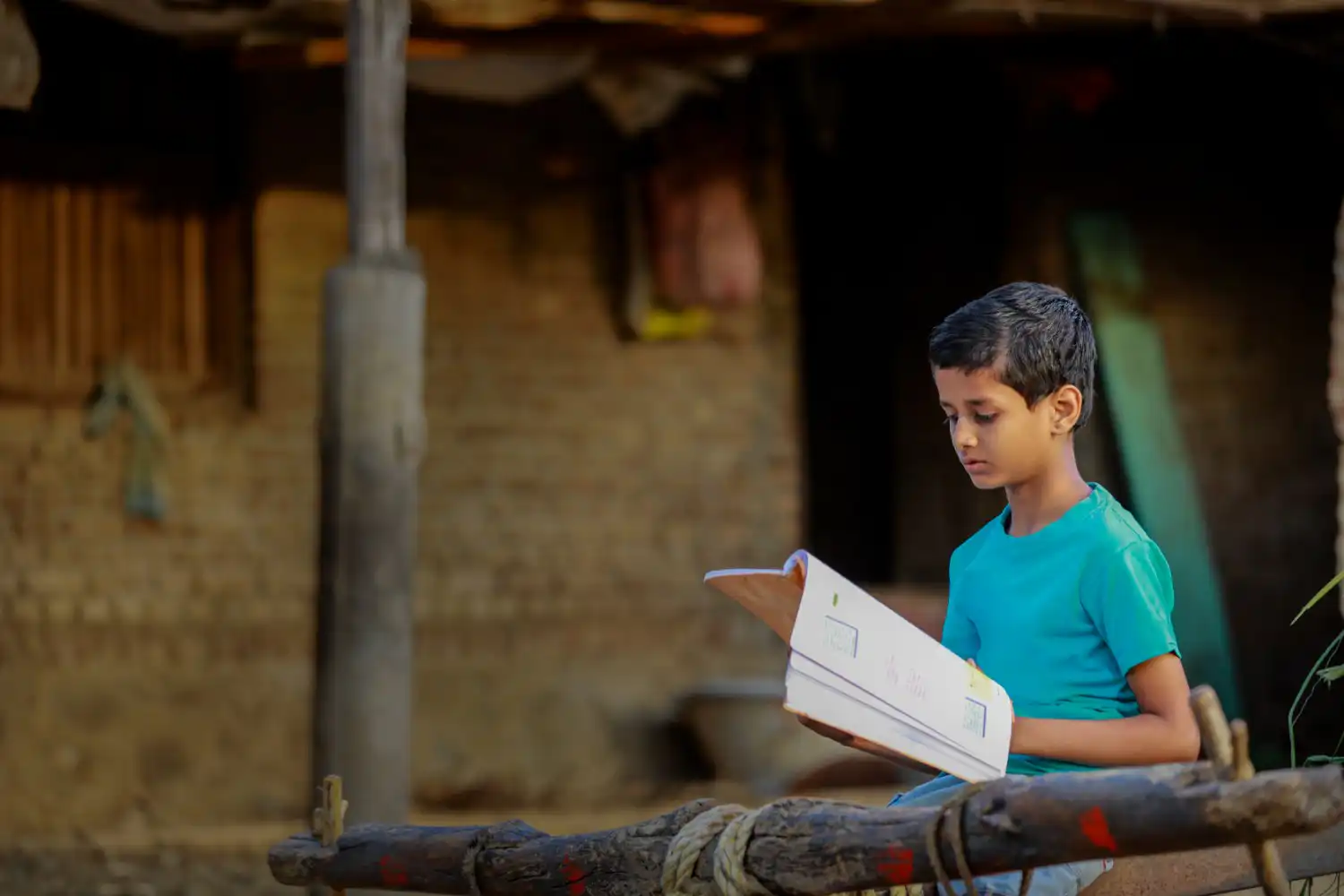

Miku (name changed) is a six-year-old. She’s very excited today as she will be going to the ‘baro school’ (big school) where her brother goes, for the first time. Her school is on Ajodhya Pahar (Ayodhya Hills), a picturesque plateau region located in the Purulia district of West Bengal. She had spent the last three years in a little anganwadi centre close to her house and has learned so much already – shapes and colours, opposite words, rhyming words. She knows many stories, can read picture books and even recite so many rhymes. Her parents are always amused at the ease with which Miku can talk to everyone and explain her thoughts and ideas simply.

At her anganwadi, Miku loved playing with blocks and puzzles the most – creating new things with squares, triangles and rectangles and solving jigsaw puzzles. She loved her Anganwadi Didi and enjoyed learning new things from her – like animal names and sounds, animal movements, where animals live, learning new games and all the exciting art and craft work. The meals at the centre were delicious too and she had learned the names of many fruits, vegetables and spices. Miku is proud that she also knows how to count and can easily distribute a pack of sweets among her friends.

Miku had a lot of friends in her anganwadi and neighbourhood. She is looking forward to a very exciting time in Class 1 now. She goes to school holding her brother’s hand and enters her classroom. She looks around for play things, toys and puzzles but cannot see anything. She spots a cupboard and thinks the playthings must be kept inside to keep safe. The walls are bare too, with no charts or posters, no pictures to look at. She feels disappointed and confused. Her classmates are sitting quietly one behind the other. Not in a friendly circle as in her anganwadi! So, she cannot see anyone’s face properly as she takes her seat – she can only see the backs and heads.

Now Miku starts feeling a bit nervous. She finally looks at the teacher’s chair and finds her teacher sleeping on it. She is very surprised and wonders if taking naps was a part of class 1 routine. Miku waits patiently for 15 minutes. But soon, she grows impatient and goes up to the teacher. Tapping him on the wrist, she asks “Sir, if you sleep in class, who will teach us new things? How will I know what to do?”

It was now the teacher’s turn to get surprised! After overcoming his initial embarrassment and unease, he talks to Miku. He wants to understand who this girl is, where she comes from and how she found the courage to approach the teacher and place her demand so easily.

He gradually found out about her anganwadi centre and her love for the play materials and books there, how her teacher taught her about so many interesting things, how she had a daily routine with play and activities and even hears about her kitchen garden. The anganwadi kendra being close by, the teacher decides to visit it one day and observe the processes there in order to understand it, even apply it in his own class.

This incident shows us how a simple question and conversation can evoke the process of transformation silently within the teacher. The incident is also reflective of the fact that children by nature are fearless, curious, eager to learn, keen to communicate and know that play and learning is serious business. They love to explore, discover and look forward to do things by themselves in order to learn.

While Miku moved smoothly from her loving home to her warm and happy pre-school experience, unfortunately, her transition from pre-school to early grade received a jolt. She got momentarily disconnected. While she’s keen and eager to learn, her potential and expectations have to wait.

Luckily Miku applied her agency to demand her learning and her teacher was open enough to learn and change himself. At this juncture, both Miku and her teacher need help and are both willing to do what it takes.

This is where interventions need to be designed and implemented, because increasing figures of enrolment and attendance or schooling does not lead to a consequent increase in learning. Learning needs reflection, thinking, planning, application, assessment and a consistent repetition of this process in the form of a collaborative process of research.

NEP’s response to the learning needs of very young learners

NEP 2020 responds to this need to improve learning in schools and calls for “a flexible, multi-faceted, multi-level, play-based, activity-based, and inquirybased learning, comprising of alphabets, languages, numbers, counting, colours, shapes, indoor and outdoor play, puzzles and logical thinking, problem-solving, drawing, painting and other visual art, craft, drama and puppetry, music and movement. It also includes a focus on developing social capacities, sensitivity, good behaviour, courtesy, ethics, personal and public cleanliness, teamwork, and cooperation” (NEP 2020, Page 7).

The National Education Policy 2020 is also reformational in nature in that it recommends structural, curricular and processual overhaul to envision a new 5+3+3+4 structure based on class and age. The first five years of the structure, is what is called the foundational stage. This has three years of pre-primary education followed by two years of early primary grades. Together these years are being seen as a single unit imagined as a learning continuum.

This continuum is envisaged to comprise of curricular and pedagogical continuity, synergy and convergence across the key domains of development (namely – physical, social emotional, language, cognitive, creative aesthetic), that are subsumed under the three larger goals.

The five-year Foundational Stage with its structural changes can however be effectively implemented only when there are curricular and pedagogical reforms towards integration and planned continuity across 3+ to 8+ years as illustrated below.

From our case study, we can see why it is essential for Miku and her friends to continue to feel connected to their previous experiences of pre-school, even after they enter the early grades. How important it is to have a curricular continuity – not just in terms of learning outcomes but also learning processes and materials. Had Miku found similar charts, posters, play and learning materials along with a motivated teacher, her learning continuity would not have received the jolt that it did. She would not have been disappointed or worried either. She would have simply continued her learning journey as effectively as before, eager to learn new things and master concepts and skills appropriate to her age and grade in areas of literacy and numeracy with ease and comfort in her foundational years.

Operationalizing NEP’s FLN mandate through NIPUN

NEP 2020 has called out the criticality of the foundational stage leading to the launch of the National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN).

Here, foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) refers to the child’s ability to read with meaning and solve basic maths problems by Class 3 (that is, by the end of the Foundational Stage). These are considered crucial skills for success in life. NEP accords the highest priority to achieving FLN.

NIPUN Bharat is envisaged as a national mission on FLN. It has been launched by Ministry of Education to ensure that every child has these skills by class 3, by 2026-27. Thus, it has been made time-bound in nature.

Those of us working in the education sector have been given an enormous opportunity to design and implement effective programs and interventions based on this policy framework to align schools with the vision of NEP 2020.

This will help to ensure that all children achieve the learning goals facilitated by effective classroom transactions and resources for improved learning outcomes. It is essential, thus, to develop long-term, holistic and comprehensive programs covering the foundational stage.

Table1: Summary of key interventions in the foundational stage

| State | State partner | Intervention type |

|---|---|---|

| Bihar | SCERT, ICDS | • FLN models on ground in co-located spaces with anganwadis + classes 1 and 2. • State support in textbook development for FLN, Classes 1 and 2 (English and Numeracy). |

| Uttar Pradesh | SCERT, Basic Shiksha, ICDS Directorate | • ECE program with anganwadis both standalone and in co-located spaces. • Support to State’s FLN Mission called Mission Prerna for classes 1, 2 and 3 in early numeracy. • Foundational stage models on ground in co-located spaces. |

| Maharashtra | SCERT, ICDS | • ECE program with anganwadi centres, models on ground, home based learning programs. • FLN program for school readiness component in Class 1 (Vidya Pravesh). |

| Rajasthan | SCERT, ICDS, DoSE | • ECE training at anganwadi centres. • Support and training of class 1 mentor teachers in co-located spaces. • School readiness component in Class 1 (Vidya Pravesh). • State level curricular resources and strategy notes. |

| Assam | SCERT, DSW, ICDS | • Early Childhood Education in Anganwadi centres. • PSE program in K-Shrenis (pre-primary sections in primary schools. |

| West Bengal | ICDS | • ECE program in anganwadi centres in curriculum, capacity building, creating model centres , parenting and state resource development. |

Vikramshila’s experiences in FLN: key challenges and suggestions

Vikramshila has been working with state governments and development partners in the area of Foundational Stage through a number of programs. This section aims to give an overview of the work and partnership model. It also provides a summary of key challenges and suggestions to strategically work towards effective FLN programs.

Navigate Multiple Departments and Institutionalize Inter-departmental Convergence: In each of our efforts the challenge is of working with multiple departments. Pre-primary education comes under the department of women and child development. Primary education (the early years too) is under the department of school education. Together they constitute the foundational stage. NEP 2020 has highlighted the need for effective synergy and convergence between departments. However, ground level program implementation is often challenging due to bureaucratic rigidities and structural inflexibilities.

For years the two departments have been working in silos. Thus, any program envisaging a continuum must first begin with dialogue and visioning. It is essential to recognize and acknowledge the strengths and experiences of each department to be able to work in collaborative unison. A strong sense of harmony needs to be the foreground. Joint consultations and workshops can be organized to achieve it.

Each department has its repository of knowledge, skills, experience with implementation, management, data collection and supervisory systems. It is best not to start from scratch or reinvent the wheel. It should be a conscious choice to review existing resources and processes and build upon that for effective and time bound results. In order to work towards realizing the FLN Mission for the children in the foundational stage, a collaborative approach is needed with strong political and bureaucratic will geared towards the best interests of the child.

Develop a Strategic Roadmap Collaboratively and Build on the Existing Work: We have found it to be immensely useful to understand where things are at present, in order to plan ahead for FLN programs. This is especially relevant with respect to the Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on institutions and individuals. Studies for scoping and situational analyses have helped us to source existing resources in terms of curricular frameworks, teacher resources, classroom inputs and children’s resources that already exist with the two departments. It has also helped us to find out about enrolments, attendance, classroom processes, community school interface, ideas of co-location and perceptions of key stakeholders.

For example, we found that in some states 3–6-year-olds are in anganwadis and 6+ is the entry age for class 1. In many other states, 5+ is the entry age for class 1. In Assam and West Bengal, for example, 5+ children are found in anganwadis as well as in pre-primary sections in government schools. In other states some 5+ children may be in anganwadis while others would be in class 1 where the age for entry is 5+. Some states have a large number of 5-year-olds out of school. Thus, large cohorts of children are missing out on pre-primary education and essential school readiness time and skills.

These learnings are important to build programs and design routines and resources. Some states have a large number of single teacher schools. Some states have classes 1 and 2 sitting together in most situations due to teacher shortage. Some others have a large vacancy of supervisory force.

It is important to develop a realistic state level strategy and roadmap based on findings from the scoping study where representatives of both departments along with SCERT, CSOs and others are included. Academics and practitioners both need to be a part of this group to develop a strategic roadmap for the short term, intermediate term and long term.

Design and Develop Comprehensive Frameworks for the Foundational Stage: In our state partnerships, we found that curricular designs, resources and learning packs are available in most states. Often, we found these to be well-designed and well-intentioned efforts; these include textbooks, teacher manuals, handbooks, reading programs, storybooks, and different classroom routines. When we mapped them across the 5-year foundational stage with the three learning goals, however, key gaps emerged. We found the lack of a holistic vision that prevented the immediate application of these resources to the school sites to respond to the call of the FLN Mission.

The existing resources, we found, were developed without a larger design framework and adequate evidences from the field. Hence, these were often piecemeal in their approach without effective backward and forward linkages. This often led to growing curricular gaps, which could not be adequately addressed. These resources cannot be seamlessly woven to address the holistic vision of NEP 2020.

Further, in order to address the shift from domain based to goal based curriculum and pedagogy, integrated thinking and design are necessary to achieve FLN outcomes. What needs to be advocated strongly is a comprehensive curricular framework for 3–8-year-olds enriched from existing resources and learnings, aligned to the three learning goals and field realities in order to meet the desired FLN learning outcomes and timelines.

These learning outcomes have been given in much detail in the NIPUN Bharat guidelines, which can be further adapted and integrated with state level learning outcomes. Modular and flexible learning packs and resources including a routine, activity bank, weekly/ monthly calendars and TLM kits need to be prepared that are in progression, age and developmentally appropriate. This can be used with children irrespective of whether they are located in school or pre-primary section or anganwadi kendra, in multigrade situations, in standalone or co-located spaces.

Handbooks and manuals on using the learning resource packs need to be prepared with details of TLM and activities. There should be a judicious mix of structure in the lesson designs as well as adequate space for autonomy and innovation for anganwadi educators and teachers. The resources are best kept simple, easy to understand and illustrative in nature, keeping the idea of progression visible.

Further the states’ enthusiasm and investments in worksheets need to be tempered with an understanding on how children learn in the early years. While worksheets can be culmination activities after introduction of concept with materials and pictures, they cannot be the primary pedagogical and assessment tools in the early years. This is a big area of advocacy in our work with different state governments.

Plan and Invest in Transformational Capacity building across the Foundational Stage Spectrum: Any education policy, no matter how progressive, is bound to fail if teachers are not capacitated as partners to be both empowered and motivated. The new FLN vision calls for a paradigm shift in approach, methods, visioning, understanding and implementation. Thus, capacity building of teachers from schools and anganwadis needs to be around perspective building, attitude shifts and skill building to enable them to cater to the idea behind the three learning goals, learning approaches and their associated learning outcomes through activity based and developmentally appropriate pedagogy (DAP). There should be sessions to account for backward and forward linkages across the learning continuum and flexibility to account for multigrade and multilevel teacher situations, as teacher rationalization is unlikely to be realized any time soon.

This requires visualization and implementation of a comprehensive, modular pedagogical continuum that is play and activity based, which can be followed across the entire foundational stage from pre-school to Class 2. Joint workshops with anganwadi teachers, schoolteachers and headteachers are an excellent way to demonstrate and build convergence on ground. This has been tried by us in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand with great success. The states should also be motivated to provide for dedicated FLN teachers and ensure their continuous capacity building through trainings, workshops and academic exchanges in Shishak Sankuls and other forums. Schoolteachers and anganwadi teachers can be mutual resource persons for each other, as each has their set of strengths that can benefit the other.

With respect to assessment, the NIPUN guidelines have explicitly defined the assessment procedure and provision to measure learning outcomes on a regular basis. This includes state-led large scale assessment and school-based assessment as well. In this context, capacity building of primary teachers in both language and numeracy would be crucial. A robust capacity building plan needs to be made in alignment with state offered training programs (e.g., NISTHA). Also, there should be provision for specific and need based in-person or online training to equip teachers to adopt the idea of creating a stimulating print-rich FLN classroom (both literacy and numeracy rich) in primary grades and anganwadis. Continuous dialogue and sharing of experiences within the teacher community and between anganwadis and schools would also help to create opportunities for cross learning, mutual respect and support.

Working with the Community as FLN Partners: Regular progress updates and meetings with community members and parents are crucial in ensuring that there is strong reinforcement of FLN mission and goals at home as well. In order to do this, community-based Shiksha Melas, TLM Exhibitions, Reading Festivals etc. can be undertaken both in school premises as well as in community spaces. Regular PTMs need to be undertaken and institutionalized along with other school events encouraging community involvement and participation.

Our ‘Khushi ka camps,’ reading festivals, reading camps, parenting and homebased learning programs, together with community chaupal sessions have emerged as successful interventions that promote interlinkage of schools, anganwadis and communities. These events are holistic in nature, as issues of enrolment, transition from AWC to schools, school attendance and regularity, nutrition, safety and habits also get discussed.

Continuous Mentoring/Coaching Support: The new education policy recommends continuous mentoring support to teachers by the system’s academic cadre. While BRC and CRC are the designated academic cadre at block and cluster levels, their role in enabling and supporting teacher networks and academic discourses has not been proven yet. In the context, strengthening the existing structure and equiping their resource persons is needed, so that they can undertake the necessary supportive supervision, coaching and mentoring to realize the FLN Mission.

In order to do this, we are supporting state governments to develop protocols and tools for mentoring. We find that it is challenging for teachers to handle multi-grade and multilevel situations, especially due to teacher shortage, inadequate classrooms, and lack of required teaching learning resources. Effective time on task is also a key issue that emerges from the field. In these cases, strategic handholding support onsite and through meetings, with practical inputs, suggestions, guidelines and demonstrations can go a long way in helping teachers overcome their genuine problems. Tackling effective time on task is so much more doable when challenges are resolved in a collaborative manner with mentors and peers.

Concerted efforts around inclusion and gender transformative discourse and practices: NEP 2020 emphasizes an inclusive classroom environment. Inclusion in our programs encompasses not just special needs but also gender inequality, and sociocultural and economic disadvantages. As such, our programs on FLN work towards ensuring access for all children, appreciating diversity in the classroom, acknowledging each child as an unique individual, ensuring equal opportunity for both boys and girls, ensuring participation of all children in the learning process, adopting a sensitive approach towards designing activities and using resources, and avoiding any kind of disparity or discrimination.

The idea of inclusion and gender transformative practices thus need to be kept in the overall FLN discourse, its program design as well as assessment. We incorporate it in all our content. This includes stories, poems, artwork, worksheets, charts etc. In our pedagogical methods, classroom environment, teacher trainings as well as supervision tools we strive towards inclusion and gender-related egalitarian transformation as well. We practice inclusion with respect to attendance, participation and engagement, of both girls and boys and children with social disadvantages and special needs. This focus is especially important because identity and ideas of differences as well as attitudes of collaboration and mutual respect develop and get ingrained strongly in the foundational years.

It is these early years that can make significant difference in the life of a child, her family and the society at large. Creating communities of practice is the first step in realizing the vision of the foundational stage.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!