Learning spaces for active citizenship

Vinita Gursahani Singh and Neha Yadav, in their article titled “Learning spaces for active citizenship,” reflect on their experiences in making citizenship education robust through real-world, project-based, civic action by students.

Active citizenship

Active citizenship is usually seen in reference to democracy or democratic systems. Political science scholars like Putnam, Tocqueville, among others, largely agree that laws and institutions alone are not sufficient for a democracy to flourish. The quality of a democracy depends on the “civic virtues and engagement of citizens” (Putnam et. al. 1994; Hoskins 2014).

This means that democracies need citizens willing and able to act toward bettering their lives and communities. In other words, democracies need active citizens or active citizenship. This is an important direction to India, as the world’s largest democracy, and to us as well, as guides and educators to the children of the world’s largest democracy.

Bryony Hoskins, who has worked extensively on active citizenship indicators with the European Commission’s Centre for Research on Lifelong Learning, broadly defines active citizens as those citizens who engage in a “broad range of activities that promote and sustain democracy” (Hoskins 2014).

Unpacking this definition points toward two aspects. First, that active citizens undertake activities. Depending on the context, there could be a range of these – from voting, volunteering, petitioning, campaigning for elections, protesting, and holding public hearings, etc.

The second aspect is that activities on their own are not sufficient. Active citizens must base these activities on certain values and principles that are essential for a democracy. These could include respect for others, freedom of choice, equal voice and participation, respect for the law, among others. The important thing then is that activities per se without values and principles can become unguided. These may lead to non-democratic activities that can harm other individuals and social groups.

This brings us to the question: what does it take to develop active citizenship? Insights from early Roman and Greek conceptions of democracy, outlined a need for citizens to learn the techniques and competencies of acting in pursuit of solidarity and the common good.

This points toward two things. That active citizenship is essentially a learned process. And that developing an active citizenry needs deliberate and effective capacity building efforts. These involve building attitudes, knowledge and skills. This is needed for developing the ability to act, and to be able to understand the values that form the basis of a better society. This is of huge significance to us, as guides and educators of children. They are the future citizens, who will take India’s democracy forward.

Citizenship education: our experience

The foundation for active citizenship is to be built in schools. Schools’ curricula provide for conceptual learning. However, active citizenship is essentially honed through practice. Children must be able to apply concepts to spaces in and outside of school. These include community spaces such as neighbourhood markets and grounds, local institutions such as panchayats and municipalities, and family spaces as well. Children can relate pedagogic knowledge to daily living in these spaces.

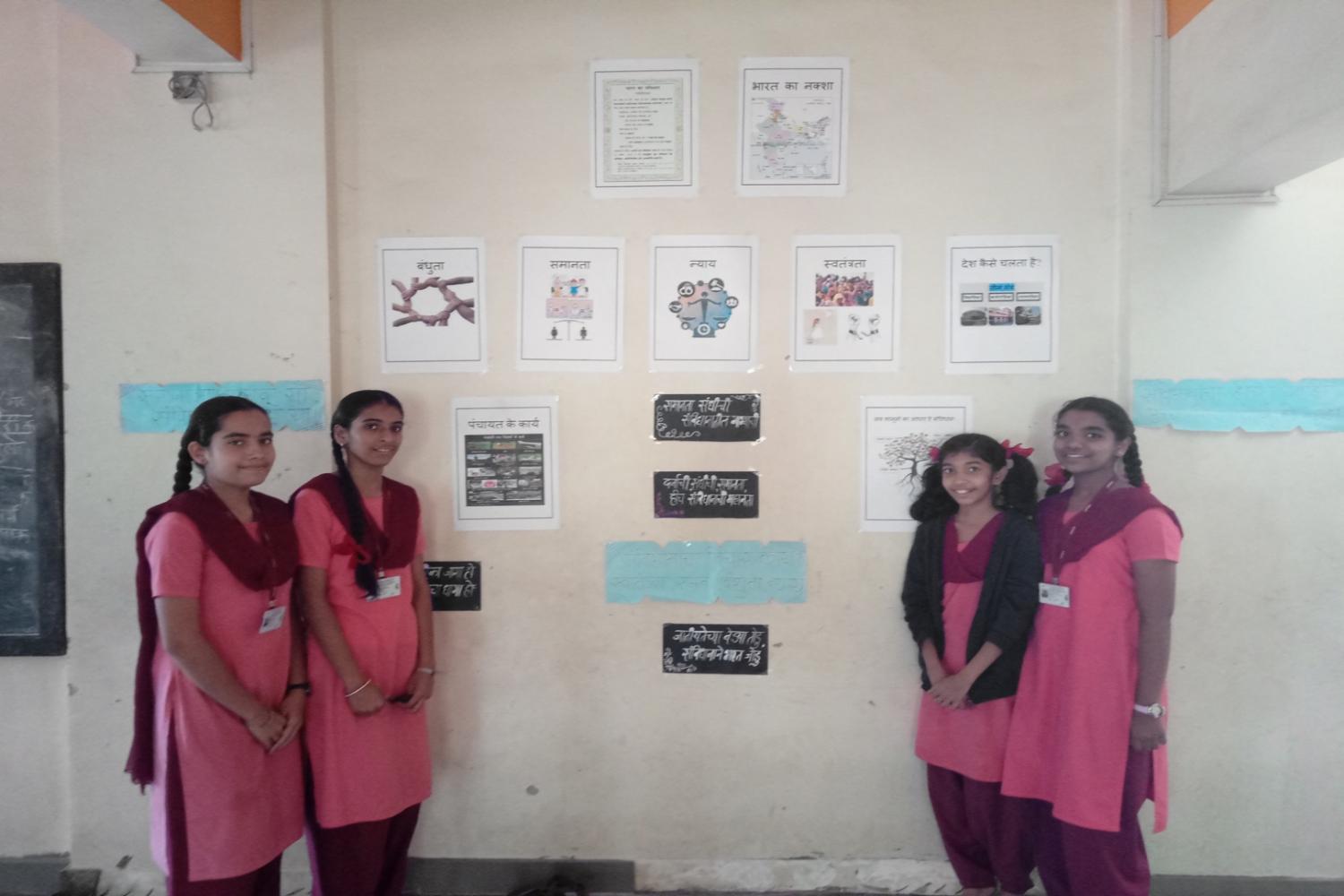

With a view to build practical, active citizenship skills, We, The People Abhiyan has been engaged with a number of private and government schools. The interventions are focused on ‘citizenship in action’. This is done through practical problem solving for students of grades 10th, 11th and 12th. Teachers or champion students are oriented on facilitating project-based learning. This takes place through Civic Action Projects (CAPs), which students take up.

The CAPs’ focus is on identifying a pressing development issue that students face within their communities. Then, they link the issue with the constitutional framework and try and become familiar with the relevant laws and government services. They also attempt to understand the role of other stakeholders. Finally, they undertake civic action to address the issue.

Usually, these CAPs are related to local issues. These concern local governance bodies like the Municipal Corporations. The practical application of concepts learnt in the classrooms helps in knowledge retention and skill building.

For example, Jnana Prabodhini and City Prides School chose to work on the issue of Solid Waste Management. They underwent a systematic process of doing field research and desk research. They then met with the officials of the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation. The detailed field research done by City Pride, on how 300 families manage their solid waste, was appreciated by corporation officials.

Students then made individual plans of how they would like to work upon the issue. They engaged in diverse activities to combat the challenges related to solid waste management. They wrote letters to vegetable vendors asking not to use plastic bags.

They were extremely glad to see that one snacks centre listened to the request and started using paper bags, instead of plastic ones. Students from younger grades made around 400 paper bags on their own and distributed these to nearby shop owners.

This is just one among hundreds of projects taken up by young people. They have engaged with state authorities, gram panchayats, housing societies, and their community in general, to resolve various civic issues. These include those related to streetlights, zebra crossings, potholes, stray animals, uncovered drainage, community libraries, among others. The CAPs have created spaces for learning and practical experience for young people to engage with their communities and relate pedagogical knowledge to daily life.

Learning spaces for citizenship education

The extraordinary opportunity in citizenship education is that citizenship is a continuous experience. There is no point in the day that one stops being a citizen. Where and how one sleeps, to what one eats, and how one interacts with others, everything relates to our citizenship. Our fundamental rights and responsibilities are at play at each moment. This gives educators scope for helping children learn from everyday actions outside the boundaries of schools.

These actions could be in the realm of the self. The guide to reflection could be, for example, asking oneself, “How did I treat someone today? How did I react to someone’s views on my caste or religion or gender today? How can I stand up for my rights?” By taking examples from everyday actions, educators can help children practice active citizenship in the ‘here and now’.

The other realm of actions is the immediate community where children live and relate. Here, children could identify the civic issues and social problems they face. These could range from, “There is not enough water in our locality,” to “The streets don’t have lights,” to “Garbage is strewn everywhere.” It can be anything that is of concern to the students, and they want to do something about.

Educators can make any of these inquiries a project for learning and reflection. If there is a possibility, the inquiry could be extended to identifying and working with stakeholders who can do something about the problem. This gives students the opportunity of ‘learning by doing’.

What is needed from us

In India, despite directions from NEP, active citizenship has not been cultivated in the school system in an adequate manner. Thus, students come out of schools uninspired and ill-equipped with the values, knowledge and practical skills needed to participate in democracy and development. At the same time, communities face governance and development issues that could be addressed through citizen engagement.

Additionally, essential skills of active citizenship like critical thinking, questioning, dialoguing, and problem solving are not seen as ‘desirable’ by governments’ education departments. In the words of a senior official of Education Department, “You would teach the children how to question! Then they would question even their teachers!”

The answer for us is clear. If such spaces are not available within schools, we must create these outside. CSOs working in education, who are working to build active citizenship, must bring in this focus in learning spaces beyond schools.

Another clear aspect is that there is an intense need for advocacy with governments. When governments view active citizenship as a threat rather than as a necessary feature of democratic education, then it serves no one – least of all the young children who hold Indian democracy’s future in their hands. The way forward for us then is to continually and consistently engage with governments to help them centre and front the tremendous opportunities of citizenship education in everyday learning spaces.

BR Ambedkar pointed toward the importance and enormity of this task when he wrote, “Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated.”

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!