Learning through work

The present issue of Samuhik Pahal focuses on the topic of ‘Work and Education.’ Instead of focusing on how the brave new world of work, which is shifting its contours on an almost everyday basis, is changing our systems of education, we choose to focus here on work itself as a mode of learning. In this issue we also share with you, innovations in learning strategies that are showing us ways of ‘learning to learn’ and of ‘being and working,’ which promise to help us take care for ourselves and of the places we inhabit.

The environment in which we live in India seems to prioritize a specific relationship between work and education. This relationship is essentially an instrumental one, in which education is supposed to lead to jobs/work, preferably those that do not involve physical labor. Education and work have come to be seen as completely separate. Education is seen as ‘mental.’ It is perceived to be happening in the ‘academic’ environment of classrooms. It is not seen to involve productive work, especially physical work.

Our current popular and dominant understanding of education in the country ignores the fact that good education – learning that truly stays with the individual and become a part of their being and skillsets – often allow for the involvement of ‘the whole self,’ involving the intellect, the emotions and the body. The dominant understanding also does not cognize that there are some things which are learnt only when one engages in live, actual work or projects. And these can never be learnt in purely academic settings. This is as true for learning about sustainable agriculture and ecosystems, as it is true for learning science or robotics. It is ironic that while this is commonly understood in higher education – which is why we have internships and apprenticeships, etc. – it is completely ignored in school education.

This has had many problematic consequences. Because the thrust is almost exclusively on mental and academic learning, it is only a certain category of students who find an ‘instrumental’ value in school education. This kind of learning and the jobs they lead to, are seen as having great prestige, and as being aspirational, etc. In comparison, learning that requires productive work, and especially physical labor, are seen as second grade.

However, other students, who seem to be the majority, find education alienating and/or worthless for practical use. This gets reflected in high dropout rates and poor results. Through this process, school education itself has come to be devalued. This is especially true for marginalized communities. It is often perceived by them to be not leading to well-paying jobs in the formal sector. It is seen as either a mere gateway to college education or to some short-term professional training that, more often than not, leads to a low-paying job in the service/ manufacturing/automobile sectors. The middle /upper middle classes still know/have faith that ‘good’ school education will lead to ‘good jobs’ though.

This simplistic understanding of education as training for a specific job seems especially flawed in our times, which are characterized by rapid changes in the economy and society. Such an approach does not address the fundamental objectives of education. These goals relate to individual flourishing, maximizing potential, contributing to society in one’s unique ways, and preparing for citizenship in a democratic society with competing priorities, etc.

On the other hand, it carries the threat of rendering most of the people so narrowly trained, redundant pretty soon. Yet another problem with such a way of relating education with work is that it sees a human being as being neatly divisible into a body, a mind and a soul/heart, and it prioritizes the training of the mind over anything else.

Our present system – there are some exceptions – consigns those that it sees as academically underperforming (hence with underperforming, supposedly below-average, minds) to vocational training/education programs. They are supposed to get trained, pick up the skills necessary to get a job, and become ‘socially useful.’

As an antidote to such a state of affairs, some people advocate holding on to, and acting upon, a liberal understanding of education, which sees institutional, formal learning as a way of training the mind, and as an end in itself. The advocates of this position argue that the goal of education is simply to impart a love of learning and the mental attitudes that Western Enlightenment sees of value, such as that of reason.

What the blind adoption of a liberal approach to education in a country like India misses out on, is the colonial context in which such a system was introduced in India, and the existing inequities it can, and does, accentuate in the country. Thus, the liberal antidote is problematic.

However, in India itself, we have seen the development of multiple alternative approaches that can perhaps provide a counterpoint to both the liberal and the ‘instrumental’ relationship between work and education. We just mention two traditions here. We mention these two not only because of the importance of the ideas contained in the approaches, but also because the influence they have had on the practices of many schools and organizations across the country.

The first is Mahatma Gandhi’s Basic Education. In this framework, productive work is itself seen as a pedagogic tool to learn academic subjects. However, in this tradition, work is not reduced to an instrument for learning subjects. It fulfils multiple roles.

These include relating to the community with productive work, developing the capacities of the body, and perhaps the most important one, internalizing the dignity of labor. Central to this process are both the learner’s labor and the facilitator’s contributions. The resource section of this issue of Samuhik Pahal contains three documents which try and grapple with these Gandhian ideas in some detail.

One can contrast this Gandhian formulation with Aurobindo Ghosh’s conceptualization of education, central to which is the idea that nothing can be taught. What the process of learning does in this framework is to aid the learners in the unfoldment of the potentialities that already exist within them.

Consequently, a key way in which the human child can effectively learn is by doing bodily work – especially by using the body through play, exercise and craftwork, to know themselves and their environment better. Both these approaches have the potential to radically alter the ways in which we can look at and think about the relationship between work and education.

Both of these bring the idea of the whole person into education, Gandhi with his idea of training ‘the hands, the head and the heart’ and Aurobindo with his concept of integral education. And both of these approaches make bodily work a central element of the learning process.

We already have a long body of practice in ‘work and education’ (almost across three generations) using the ideas of Gandhi and Aurobindo. It is high time we started actively learning from these experiments in a systematic and systemic manner. This is especially because the challenges in front of us are many.

We live in a country that arguably suffers from all the ill effects of industrialization, such as pollution and erosion of the natural resources base, and alienation of individuals and communities, with relatively little of its redeeming features, such as mass employment, and development of scientific rationality.

Making work-based education one of the central pedagogic methods, if not the only one, in our schools might be one good way to bring work to the center of learning processes for our children. This allows for other positive processes to emerge, for example, bringing community members into the classroom, especially those engaged in skilled, productive work. It can also help children develop important life skills and a deeper relationship with their bodies.

In fact, work-based education has the potential to transform our workplaces and the space learning has in them as well. There is a movement towards de-credentialization across the globe, which strives to open up opportunities for work, especially in the formal sector, by removing the need for credentials such as post-school academic degrees and diplomas. The workplace then itself becomes the space where the required learning take place to ease into the job role in particular and subsequent career/ work-life in general. This especially helps those from marginal backgrounds, who find it difficult to pick up credentials.

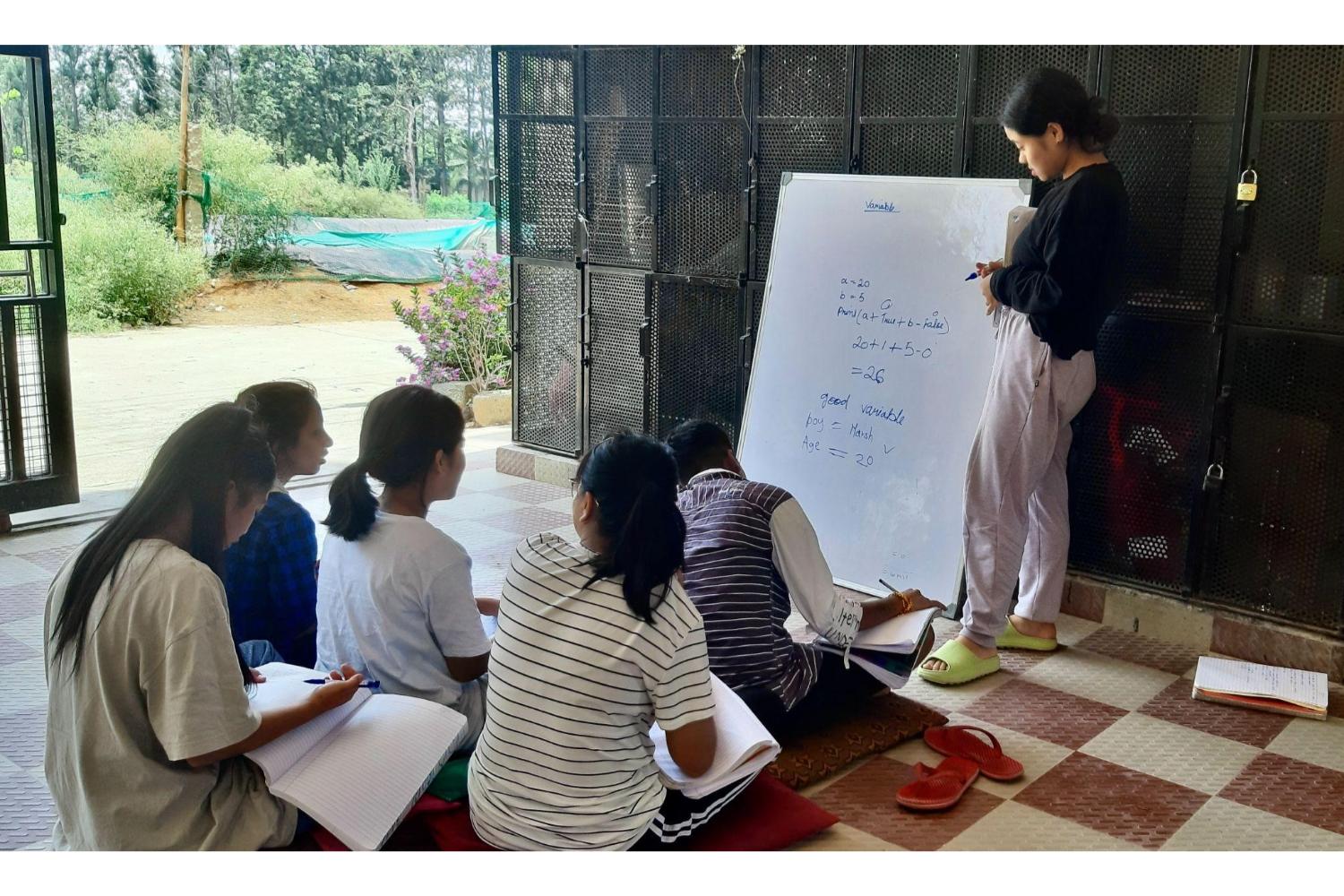

One can get work into institutions of learning. One can also get opportunities for learning into the workplace in radical ways. Organizations across the country and the world are innovating and experimenting with multiple modes of exploring this space. Many of these experiments are to do with the teacher-student relationship.

In the conventional workspace, this often translates into fostering mentor-mentee relationships, in which learning happens through a process of apprenticeship. In the average school, this can take the shape of the conventional teacher-student relationship morphing into a learner-facilitator one.

Combining work and education makes better pedagogic sense in itself. The instrumental view of using education as a mere tool for training our children as future workers is not a very wise guide for practice in the current times. This is because we can’t even predict what jobs the next generation will have. Thinking that purely academic learning will prepare them may be flawed.

Exposure to productive work might allow them to better pick up the general skills which seem much more important now. Closer integration of the two – work and education – will also help reduce the artificial ‘prestige’ gap that has been created between the so called manual and cerebral work.

Keeping work at the center of our learning experiences may also help in democratizing our work spaces and learning institutions by making our engagement with marginalized social groups, who have been kept out of formal spaces for long, a meaningful one. It can aid us in expanding the sites of learning as well, and in opening up the horizons of what we mean by education.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!