One size doesn’t fit all – A practitioner’s experience of inclusive classrooms

In her article titled “One size doesn’t fit all,” Chitra Shah provides a grounded perspective on what it takes to create inclusive classrooms through collaborative work with the government.

Integration of children with special needs

“Why don’t you teach your children science?” – This question by Dr Judith Newman from the Early Child Care Program of University of Oregon, USA, in 2013 during her first visit to Satya Special School got me thinking. Satya Special School has been providing special education, including rehabilitation and therapy, to children with special needs (CWSNs) since 2003. While this was a pioneering effort in empowering CWSNs and changing the conversation around disability in the region, it still wasn’t reflective of true inclusion.

Quite often, when I looked around our centres, I would ask myself, “Can we offer some of the children with mild and moderate Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) formal mainstream education?” Having read about the integration of Children with special needs (CWSNs) in high-end private schools in various metros, we were confident that we would succeed. We approached a few acquaintances who were heads of private schools in Puducherry.

We thought, given the simple hierarchy in most private schools, where the founder is generally the decision maker too, it would be easier to include CWSNs. To my disappointment, every school denied this request, stating that the other parents would raise concerns. With this avenue closed, we then focused our efforts on government-run schools.

Around this time, there was a lot of emphasis from the Central Government on Right to Education, Education for All and Integration of CWSNs in mainstream schools. Though Government of India had made it mandatory to include CWSNs, ground realities were very different.

I remember when I took a wheelchair user for admission, the headmaster of a rural government school took me to an already crowded classroom and asked me, “Where is the space for a wheelchair?” Indirectly, he was refusing admission. The government also saw inaccessibility and lack of disabled friendly infrastructure as a roadblock. It allocated a large portion of the budget for building ramps and accessible toilet facilities.

Engaging with the public education system

To justify the budget expenditure on infrastructure, the initial focus of the Government was on the enrolment of CWSNs – enrolment, not integration. In fact, I was asked by a senior official in the Education Department to simply enrol the CWSNs and ensure that they come to the school once a month for attendance. “They can still get an 8th std certificate, which would help them in future employment opportunities,” he claimed.

Quite often the officials were happy to copy a model that has been implemented in the southern states. There was resistance and apprehension to adopt a new practice, as they felt it was highly risky and would lead to a negative consequence and political interference. Even if we were able to convince the field or mid-level officials, the decisionmaking process in the government is slow and cumbersome.

There are multiple layers of approval and lengthy procedures, which can delay the implementation of the incremental change. Officers are often transferred at the blink of an eye. Convincing the new incoming officer and repeating the entire procedure would leave us exhausted. However, we managed to hold on to the belief that it needs one nod, one person to accept the change.

The challenge for the government was not just about creating the right environment. It was also about changing teachers’ mindsets. Even today, every time we meet a group of mainstream schoolteachers for an orientation and sensitization program, we get mixed responses. These range from a sympathetic teary-eyed teacher to a teacher who felt having a CWSN in the classroom would add to her work burden or a teacher who felt she lacked the competency to handle the child. There have been teachers who even asked, “Why should we integrate them, what can they do!!” So deeply entrenched was the societal bias against CWSNs that it had pervaded the sanctity of the classroom, where all are supposed to be equal.

Due to the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, Department of Education had organized several online workshops for providing insights and inputs to ensure CWSNs’ inclusion. The Director of Education, Government of Puducherry, at the time – Mr Rudhra Goud – had clarity of thought about inclusion. He was also willing to go the extra mile to ensure that the inclusion of children with disabilities becomes a reality.

Making inclusive education work for CWSNs in government schools: the importance of bureaucratic initiative

Inclusive education for CWSNs was one of the major interventions of the erstwhile Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), RTE and RMSA schemes. Under Mr Goud’s leadership, from the year 2018-19, Samagra Shiksha in Puducherry emphasized on improving quality of education for all students, including CWSNs. Thus, various student-oriented activities began to get implemented.

These included identification and assessment of CWSNs, provision of aids, appliances, corrective surgeries, Braille books, large print books and uniforms, therapeutic services, and development of teaching-learning material (TLM). There was also a focus on building the overall environment and orientation programs to create positive attitude and awareness about CWSNs’ needs. Purchase and development of instructional materials, in-service training of special educators and general teachers on curriculum adaptation, also took place. Stipends for girls with special needs (which was until then just part of the legislation and rules laid by the Center) also started being provided. Enrolment of CWSNs, and appointment of Special Educators, helped in getting many CWSNs integrated into mainstream schools.

As the numbers kept increasing, so did the challenges. The presence of a special educator made families of CWSNs believe that their child would improve in an inclusive setup. However, most special educators were experienced in handling only a particular type of special need, either visual impairment, or hearing or IDD.

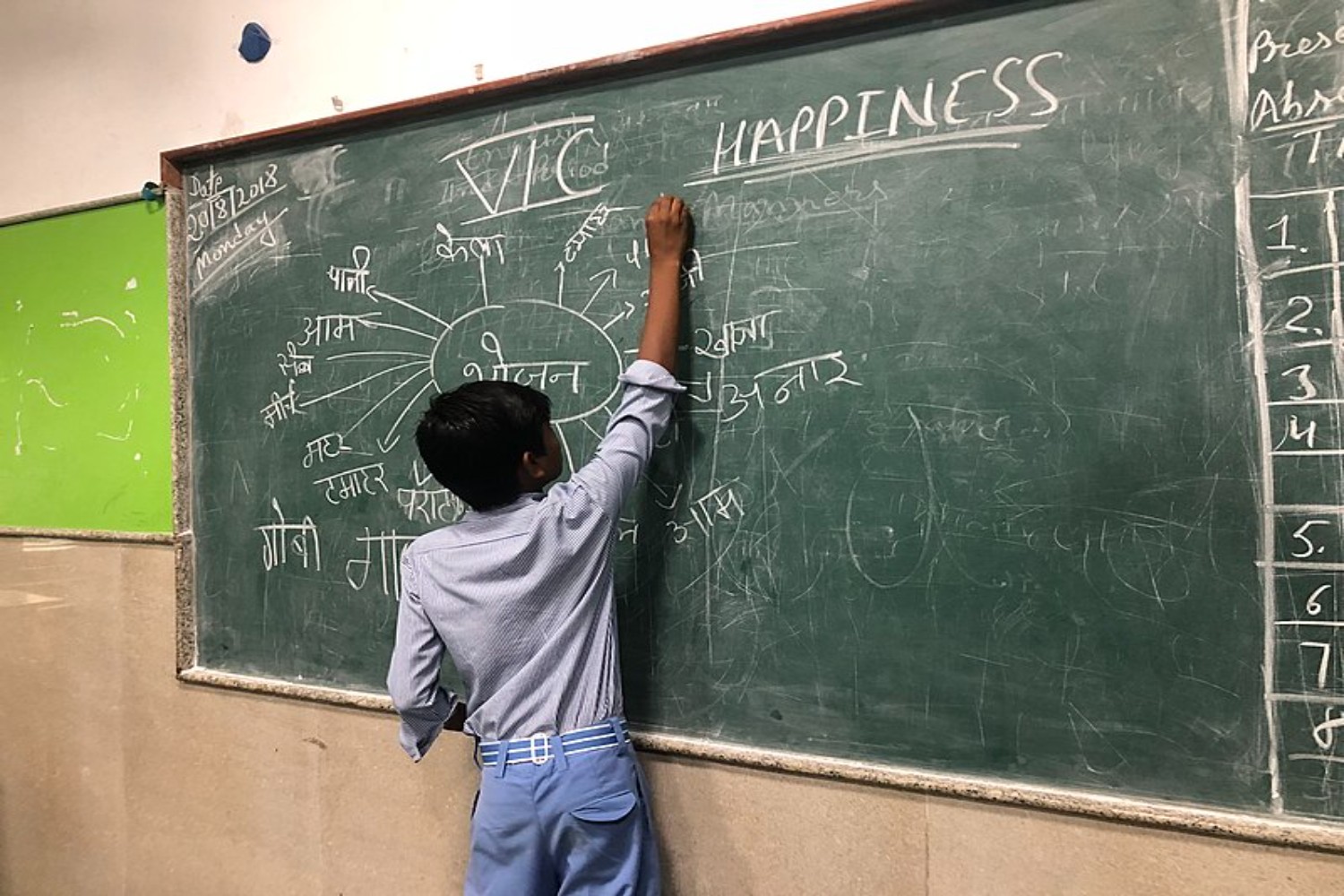

An inclusive school meant a mixed group of children with varying special needs as well as age groups. The “one size fits all” concept did not give the desirable results. Special educators themselves found handling children with IDD, especially those on the autism spectrum, to be a huge challenge. Lack of sufficient experience in handling these unique children resulted in Satya taking the initiative to reach out to the government with a plan to start inclusive classrooms in mainstream schools.

Ideally what would work well is to have an induction training program prior to appointment, where all the skills needed at the classroom level are imparted. Alternatively, the government could work with teachers training institutions to ensure that regular teachers are trained for 3-6 months on special needs. The above would only be a stop gap measure. However, the solution would be to ensure that irrespective of the learning levels of the child, the teaching methodology remains activity-based, and the teaching methodologies are universal.

What inclusion looks like in Puducherry’s government schools

Our discussions with Mr N. Dinakar, State Project Director, Samagra Shiksha, resulted in signing an MOU for the implementation of inclusive classrooms in mainstream schools. Five (5) schools, both urban and rural, were earmarked for the collaboration. Under this MOU, Satya would integrate CWSNs, especially those with IDD and autism, along with a special educator.

One such school was Colakara Nayakar HSS. Here, in addition to an inclusive classroom, we also had an inclusive playground. This provided the much-needed space for ensuring inclusion and integration beyond the classroom.

Initially, the response of the headmaster was unwelcoming. He did not have complete faith in the outcome of the project. He saw it merely as an image-building exercise for the Education Department. The school already had a special educator who was not keen in sharing her space with an external entity. There were incidents where some of the other teachers were harsh toward the Satya team. They felt we were wading into their space. At times, we were met with hostile comments.

All this called for some out of the box thinking. We prepared greeting cards for every single teacher in the school on Teachers Day and personally handed it over to them. This made them feel special. We offered to share the smartboard to watch the launch of Chandrayan. We also conducted some inclusive events, such as painting competitions, etc.

However, the icing of the cake was when the head of the state, the Lt. Governor of Puducherry, made a visit and congratulated the entire team. This recognition, and the unconditional acceptance shown by the neurotypically developing children, also helped us to overcome the initial roadblocks. The children managed to find themselves comfortably planted into the school atmosphere. Day by day, their interactions with their peers and the whole school has evolved into mutual acceptance in a healthy environment.

The slow but steady path for changing mindsets for inclusion

It was only the adults, i.e., parents, teachers and school management that seem to have had differences and opinions about including children with different needs. Among the neurotypically developing children, the acceptance was spontaneous, once they understood what it means to be disabled. “Their enthusiasm is infectious,” says Mr Saravanan, State Coordinator Inclusion of CWSNs, Samagra Shiksha, the person responsible for the inclusive classroom program to take shape.

In the words of Selvam & Mani from the Govt. HSS Tirubuvani, where we also installed a disabled friendly playground, “Initially we made fun of them. But after the stimulation lab we attended, we understood how difficult it is for them to even do routine activities that we take for granted. Now every time I see a pothole on the road or a log hindering movement, I immediately think about the wheelchair users.

“I personally went to the village headman and explained why they need to do the repair immediately. It is scary to think how a simple pit dug on the road can prevent a fellow student from coming to school – as he cannot manoeuvre around the pit. Today wherever I go, be it a beach, temple or wedding, I look at accessibility. My friends and I plan to spread Reflection the message about inclusion and how it is important to make CWSNs access education.” The success of a project truly depends on the team. We were delighted to witness one such team in Karaikal.

Here, the school’s special educator, all the teachers, the headmaster, and the school management, engaged wholeheartedly with the initiative. In this, they were ably supported by the Deputy Director and other officials at the Department of Education in Karikal.

In conclusion

All the above efforts and the progressive government policies aided by the NIPUN Bharat scheme, and Vidya Pravesh programs, have resulted in the Government of Puducherry setting up Early Childcare Education Centers in all government schools. These follow the FLN – Functional Literacy and Numeracy – syllabus.

These centers try to ensure activity-based learning for all children, irrespective of their learning levels and abilities. This, we hope, will result in better acceptance of CWSNs across all age groups and ensure that social inclusion becomes a reality.

As Mr Rudhra Goud, Director of Education, shares, “Teacher psychology also needs to be considered, because patience is very important in providing services to students with disabilities. Hence teachers’ training and capacity building is our primary focus.”

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!