Teachers’ well-being: stories from the ground

In the “Ground Zero” piece, Dravina Seenivasan discusses the work of three organizations from across the country to show why keeping teachers’ lives, lifeworlds and agency at the centre of their professional development is the most important part of the process.

What are the different roles a teacher plays in the system? On any given day, what are the different expectations that are placed on them by the students, principal, administration, communities and the larger systems? Who are the people in the system who trust, appreciate and recognize their work in its entirety? How can we enable their learning and development while recognizing the larger context?

One can hold these questions at the core, to explore what impacts teachers’ development, while keeping in mind their contexts and needs. There is an undoubted growing pressure on teachers to complete a barrage of duties. These include writing documents, digitally entering data, picking up and distributing materials, completing administrative tasks, and so on. In a race to compete with global education standards, there is a directional shift to collect data, collate and share student learning data, follow safety protocols, etc.

The only way to get through that big list of tasks for a teacher, is to be efficient. An increased focus on improving efficiency, leads to a culture of urgency in task completion and a view that a successful teacher is one who completes all tasks on time. This does not give them the time and space to be with students and enable learning. A journey like a student’s learning, which is meant to be transformative and powerful, is reduced to a series of tasks and milestones that are often rushed.

A culture of performance, incentives, accountability and competition has become entrenched in the current system. This has been changing the dynamics of engagement between teachers and students, school managements and teachers, CSOs, public administration and teachers and so on. These play a big role in a teacher’s day, energy levels, motivation, and the time she gets to teach. For any teacher development program to be successful, it must be rooted in this context. Is that even possible? Is there space to imagine a paradigm where this context is taken into account, while we keep teachers as a whole at the center, weave in aspects of care and well-being into a program?

In this article, we will look into the work of three organizations that work with teachers keeping their well-being, learning and development at the core of their interventions. The objectives of their engagement include important themes such as inclusive learning, literacy, and experiential learning for students. Their commitment, long-term lens, and holistic perspective provide key insights into how the system can enable teachers’ well-being in the short and long terms toward improving the quality of education for all children.

Prayas Prayas is a not-for-profit organization working in Jaipur, Rajasthan. The organization began their work in 1996 with a vision of enabling inclusive education for all. Over the years, the team at Prayas have set up two schools in Jaipur. They have worked with children in mainstream public schools and run a home-based therapy program helping families to support children with special needs. They have also developed courses to build capacity in individuals toward inclusive education, and much more. They set up the first successful integrated school in the state. A key aspect of their program in setting up the integrated school was building capacity in regular in-service teachers to become effective special educators through a combination of trainings and on-the job coaching.

Upon successful implementation of their program in one school, they began working with twelve government schools in the district. The goal was to replicate their model of an integrated school. Over the years, they have conducted several workshops for teachers to build their capacity in the methods of inclusive education. Special educators from Prayas have supported teachers in classroom by sitting with children with special needs and supporting them to learn the concepts taught through focused pedagogy suitable for them.

However, they realized that conducting workshops didn’t have the intended impact in the classrooms. Teachers were not adopting the practices toward creating individualized plans for children with special needs. Building capacity through training alone did not allow for building relationships with teachers. One had to understand the barriers in implementing what’s taught in training.

Therefore, they altered the model and increased the engagement period with teachers. The special educators visited the schools twice every week and ensured regular conversations with the teachers. These conversations helped to recognize and acknowledge their challenges. These also enabled teachers to build trust on the special educators and not see them as external people who were there to impose newer expectations, but rather as volunteers and peers who are available to support them. The team also identified a smaller group of teachers. It built deeper engagement with them. The relationship was not one where there was pressure on teachers or a system of accountability. However, it was one where the special educators understood teachers’ challenges, identified solutions that can be implemented, and supported the entire process. Two schools out of these twelve were chosen to deepen their impact. They currently focus on a group of eight teachers in building their capacity as special educators.

In addition to building strong relationships, the team has worked toward supporting teachers with concrete resources and skills that can be used in the classroom to solve the problems faced by teachers. These include workshops on creating teaching learning materials for supporting students, providing low-cost assistive devices to enable students’ learning processes, and demonstrating the use of these in the classroom.

Lastly, they also felicitated the actively engaged teachers during their annual program. These teachers were gifted a book on disabilities. This has motivated and encouraged the teachers to continue their efforts to reach out to the students with special needs in their classrooms.

In the schools in which Prayas intervenes, teachers face numerous challenges for mainstream learning. These include student attendance, learning gaps, student behavior, and deficit of resources. Therefore, it is inspiring to learn from the organization’s work of supporting regular teachers in the system to act as special educators.

Shaheed Virender Smarak Samiti (SVSS)

Shaheed Virender Smarak Samiti (SVSS) began their work in 1992. They have been working toward a vision of a society built on the values of social justice, democracy, scientific temper and equity. The work mainly focuses on the ideas of education and women’s empowerment in the Panipat district of the state of Haryana. Since 1997, they have worked toward supporting and enabling education for drop-out and left-out children through the Jeevanshala program. This initiative has been based on alternative methods.

Based on the learnings in language learning and experiences of this program, in the year 2016, they began their work with teachers and children of eight government primary schools. The goal was to promote meaningful language teaching. Through consistent presence and building relationships with teachers, the team has been able to take the program to more schools in the district.

The organization currently works with 110 teachers across 36 schools in the district. It intervenes in these schools through a program called “Meaning making through children’s literature.” The team visits every school once a week. It supports teachers in the schools toward implementing newer pedagogy toward language learning. In addition to working on pedagogy and materials for language learning, they spend substantial amounts of time building strong relationships. This happens through conversations, informal discussions, motivating teachers, recognizing their efforts, and acknowledging the challenges in the system.

A key leverage for them to successfully implement their program and scale it to more schools in the district has been strong relationships they had built with all key actors in the system. Through the Jeevanshala Program, the team had worked alongside teachers to bring drop-out and left-out students to the schools. During the pandemic, they established community centers in the villages. The goal was with the aim of minimizing learning loss. This built trust with the teachers in the system that they shared a common end goal with the team.

SVSS had already developed a comprehensive understanding of the ground reality through their prior work. They interacted with teachers to understand their challenges in depth. This was an opportunity for the teachers to share several challenges in their classrooms related to language teaching and learning. Their engagements with the teachers showed that they mostly used traditional methods to teach language. They did not have any relevant means to identify which children were making progress, and the ones who were struggling.

The teachers also found it hard to motivate children to take books from the library to read. Many students were unfamiliar with the formal written language, as they spoke completely different languages or dialects at home. In addition to these challenges in the classroom, the system imposed several additional ones. The teacher-student ratio was very high. There were regular transfers as well. This removed any consistency or stability in the teachers’ efforts.

Toward solving some of these challenges, the SVSS team began with conversations with the teachers. They provided new TLM that could prompt teachers to try newer pedagogical strategies. Some of these have involved flexibly designing classroom arrangements to make the space better for both learning and student behavior.

To support teachers to understand students and their levels, the team provided them with assessment templates. It also supported them in executing these. School libraries, which were an abandoned space in most schools, were transformed into spaces that are useful – with recommended books and purchases. The central aspect of the approach was that when the team experienced challenges, it ideated solutions, and modeled their implementation in the classroom. Teachers were supported with creating weekly plans and lesson plans. Ideas were also suggested for implementing newer pedagogical strategies.

The SVSS team also took successes, ideas and wins from one school, and shared these with the others. This motivated teachers to try out new things. It also helped them gain recognition from the larger community. Expert teachers were identified as resource persons. They were encouraged to conduct workshops at the block level. These practices nurtured the larger community. It also built strong relationships toward the collective vision.

Over the years, the team has observed student attendance increasing steadily. There is increased engagement of children in the classrooms. Regular community visits and conversations with parents have been key in making this happen.

Moreover, most of the classrooms had students who spoke a different language at home. The team worked with teachers on how the languages spoken at home could be integrated in everyday teaching and learning processes. This has been able to create belongingness for these students in the classroom. It has also been enabling their learning and growth.

Teachers were encouraged to learn words from students’ languages and use these in classes. Students were asked to paraphrase the stories and sentences in their own language and share these in the classroom. These practices have created observable changes in the students’ classroom behavior. Teachers initially thought that it was very difficult to work with these student groups. However, upon trying these strategies, they were able to support the language learning of the students.

Vedpal from SVSS shares that to work with teachers in the long-term, one must build trust and strong relationships. This includes regular conversations – both formal and informal. One must also listen to the teachers’ challenges, model strategies in their classrooms, and work directly with children. One must also appreciate teachers and recognize the work they do. The public perception of teachers is very poor. Therefore, building a collective identity of teachers in a positive light by discussing their success and challenges in the wider community is important.

“Over the pandemic, we had the opportunity to discuss a wide range of reading material with our teachers. We read Summerhill, Totto-Chan, Krishna Kumar’s writings, and so on. These books and articles helped us build conversations on the themes of language learning and child development. We encouraged teachers to write reviews and summaries, and respond with poetry. These responses were shared with the group. This built deeper engagement,” Vedpal shares.

His comments throw light on powerful possibilities of teacher learning experiences that can be crafted. The learnings and experiences of SVSS demonstrate how teacher development gets built over a long period of time with both depth and scale.

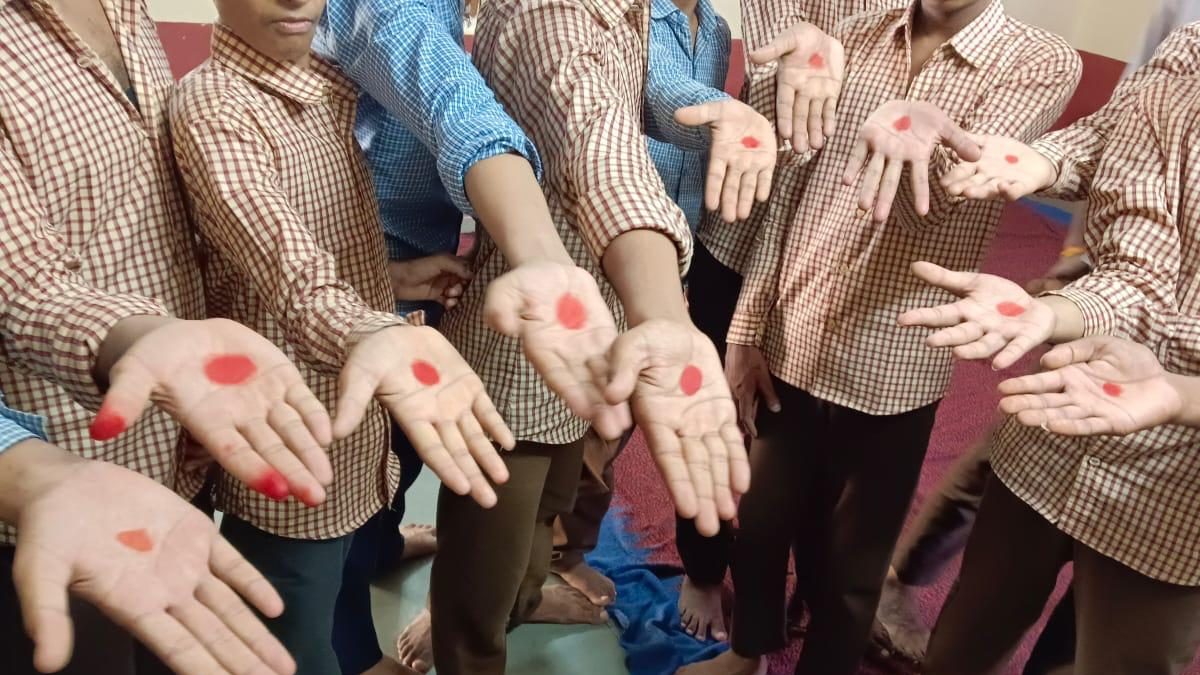

Caring with Colour

Caring with Colour has been conducting a program called the District Education Transformation Program (DETP) in the Tumakuru and Madhugiri educational districts of Karnataka. The goal of this initiative is to address the challenges of teacher professional development and help teachers adopt experiential teaching methods in their classrooms.

The teacher training program designed under this initiative has been called Sanchalana. The program has been co-designed and developed in partnership with the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET) in Tumakuru and Madhugiri educational districts of Karnataka. Sanchalana’s goal was to provide teacher training and create a community of practitioners who can share experiences and expertise on their collective journey in shifting toward adopting experiential teaching methods in their classrooms.

One of the key design goals of Sanchalana is to provide a platform for educators and teachers to come together, share insights, discuss innovations, learn new pedagogical practices, exchange best practices, and collectively work toward addressing the academic gaps in the education domain.

Caring with Colour partnered with DIETs in Tumakuru and Madhugiri educational districts to identify a group of teachers who can act as effective facilitators in the Sanchalana program. These facilitators are called “Teacher Mentors.”

These are teachers in government schools, who have good subject expertise and facilitation skills. The program required that these teachers be able to take on this additional workload of conducting the Sanchalana sessions.

With the support of the teacher mentors, the team has managed to conduct monthly learning programs (monthly learning cycles) for more than 3,000 teachers each month across Tumakuru district. This training program has helped improve the subject and pedagogical knowledge of the teachers. It has also significantly improved the teaching methodology adopted by the teachers in the system.

The training sessions are conducted on a specified Saturday each month. These are planned well in advance in the academic year. The training programs have been conducted at a Hobli level. A Hobli is an administrative unit of the system that is larger than a school cluster and smaller than an academic block. On the specified Saturdays, teacher mentors and teachers all congregated into a subject specific community of learners. Cluster and block level officials became an active and integral part of the entire process. They monitor the implementation of the training session in the Hobli learning centers.

In these monthly learning sessions, teacher mentors address teachers’ subject knowledge gaps and provide pedagogical knowledge. Hands-on experiences of various experiential activities that can be conducted in the classrooms on the topics for discussion are also shared. The hard spots that teachers have in teaching specific topics are also addressed.

Mentors facilitate the discussions. They encourage teachers to share existing practices and areas for improvement. Teachers have been learning from each other’s experiences. Senior teachers have been sharing solutions and newcomers have been able to clarify their doubts and teaching strategies. Mentors and teachers have been actively exchanging ideas, teaching materials, and new approaches.

This initiative, aptly named “Sanchalana” has fostered a dynamic and collaborative learning environment for teachers. The collaborative learning experience gained by the teachers and teacher mentors have managed to avoid a top-down approach. The initiative has been motivating teachers to adopt the learnings from the training in their classrooms.

Conclusion

The work of these organizations in different geographies of India, effectively highlights two key things. First, there is a need for voices of challenges and solutions to emerge from the teacher group. Second, nurturing communities of teachers, so that they can come together, learn from each other, and deepen their practice, supports teachers’ growth. This on-the-ground work deepens conviction in the power of teachers to transform how India learns.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!