Empowering ECCE professionals: IGNOU’s unique offerings, and recommendations for capacity building

In this interview, Dr. Rekha Sharma Sen provides insights and guidance on capacity building and empowerment of ECCE professionals.

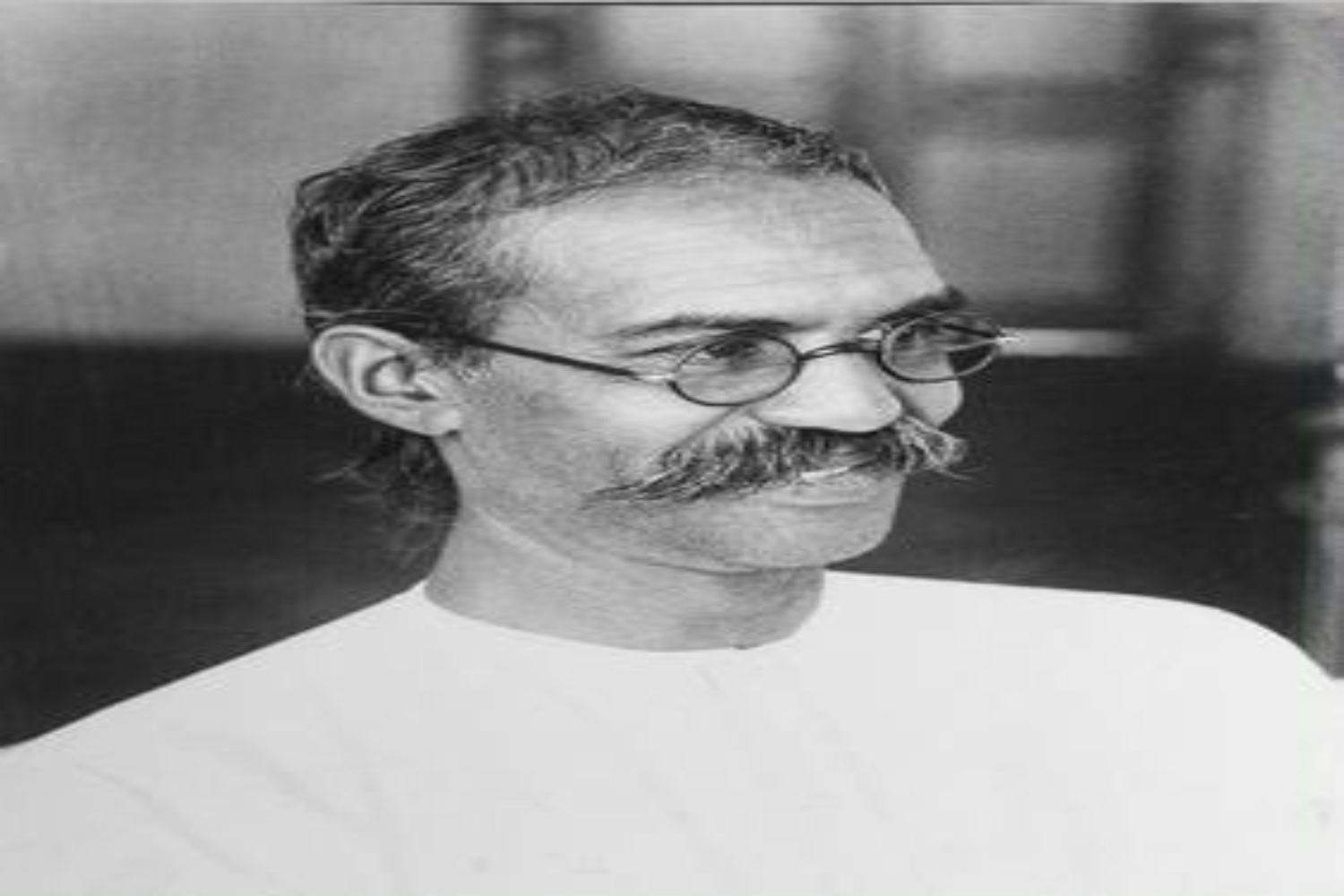

Dr Rekha Sharma Sen is Professor, Faculty of Child Development, School of Continuing Education, Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi. She has a Master’s Degrees in Child Development and Elementary Education from University of Delhi and Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, respectively.

At IGNOU, she has designed, developed and coordinated programs of study in the field of Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE). She has also developed programs for parents and family members of persons with disabilities.

Vikramshila: Can you please elaborate on IGNOU’s offering on ECCE? How can it cater to the needs of pre-school educators? How does IGNOU’s offering for pre-school educators differ from other programs currently available?

Dr Rekha Sharma Sen: Our IGNOU Diploma program on ECCE was the first open and distance learning program in the field. It was introduced in 1995, making the domain of ECCE accessible to individuals who couldn’t pursue face-to-face training or wanted to refresh their knowledge.

The course material is unique in many ways. It provides a comprehensive understanding of the knowledge about children’s development, developmentally appropriate and effective play-based pedagogy for early years, practical descriptions of activities and materials to be used with children, as well as knowhow of establishing an early childhood care and education centre.

Its uniqueness stems from its broad-based approach. This is unlike other training manuals available at that time, which primarily provided a list of activities, without building the student’s knowledge base regarding the theoretical constructs on which the play-based activities are based.

The Diploma in ECCE goes beyond just a description of activities. Instead, it explains the why, what, and how of ECCE. It empowers learners to understand the reasoning behind what they are expected to do as early childhood educators.

The program comprehensively combines knowledge about children and play-based early childhood education, with detailed understanding of child health and nutrition. It went far beyond merely providing a list of recipes for supplementary feeding. Instead, it provided an understanding of child health and nutrition, including recommended dietary allowances, balanced diets, and how to convert the recommendations into practical menus.

This component was of utmost importance, as it offered a holistic understanding of young children’s nutritional requirements, the concept of a balanced diet, and the ability to create diverse daily menus with multiple meals.

There was another vital and enduring aspect that I must credit to the course editor, Dr S. Anandalakshmy, the Former Director of Lady Irvin College, and the Editor of this diploma program. She envisioned a segment on childhood illnesses. What if the children attending the centre fell ill? What actions should the personnel and teachers take in such situations? As a result, 8 to 10 chapters were dedicated to early childhood illnesses and their management within the centre.

These chapters not only covered the centre’s perspective but also provided guidance on how to communicate with parents about signs and symptoms of illnesses affecting various body systems and organs: alimentary, respiratory, mouth, ear, nose, throat, eyes and skin.

The descriptions were detailed enough to equip learners functionally. These enabling them to know what to do, when to act mindfully, when urgency is required, and when it might not be. Of course, the course did not provide treatment instructions, as we cannot replace medical professionals. However, by offering knowledge about the signs and symptoms, we aimed to raise awareness and empower teachers to guide parents effectively. This unique aspect ensured that teachers possessed vital information to recognize potential illnesses and play a proactive role in promoting children’s well-being.

Yet another significant aspect was the explicit focus on children with disabilities. This was quite ground-breaking at the time. Inclusion wasn’t as widely discussed or integrated into early childhood education as it is today. However, we recognized its importance and dedicated eight chapters to help learners understand disability, its impact on learning and development, and how to support children with disabilities in the early childhood classroom.

It was an exceptional addition to our syllabus, promoting inclusive early childhood care and education. We delved into various types of disabilities, including intellectual disabilities (formerly known as mental retardation), hearing impairment, visual impairment, and physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy. Furthermore, we tackled the challenging topic of managing difficult behaviour in children, providing practical strategies for teachers to navigate such situations.

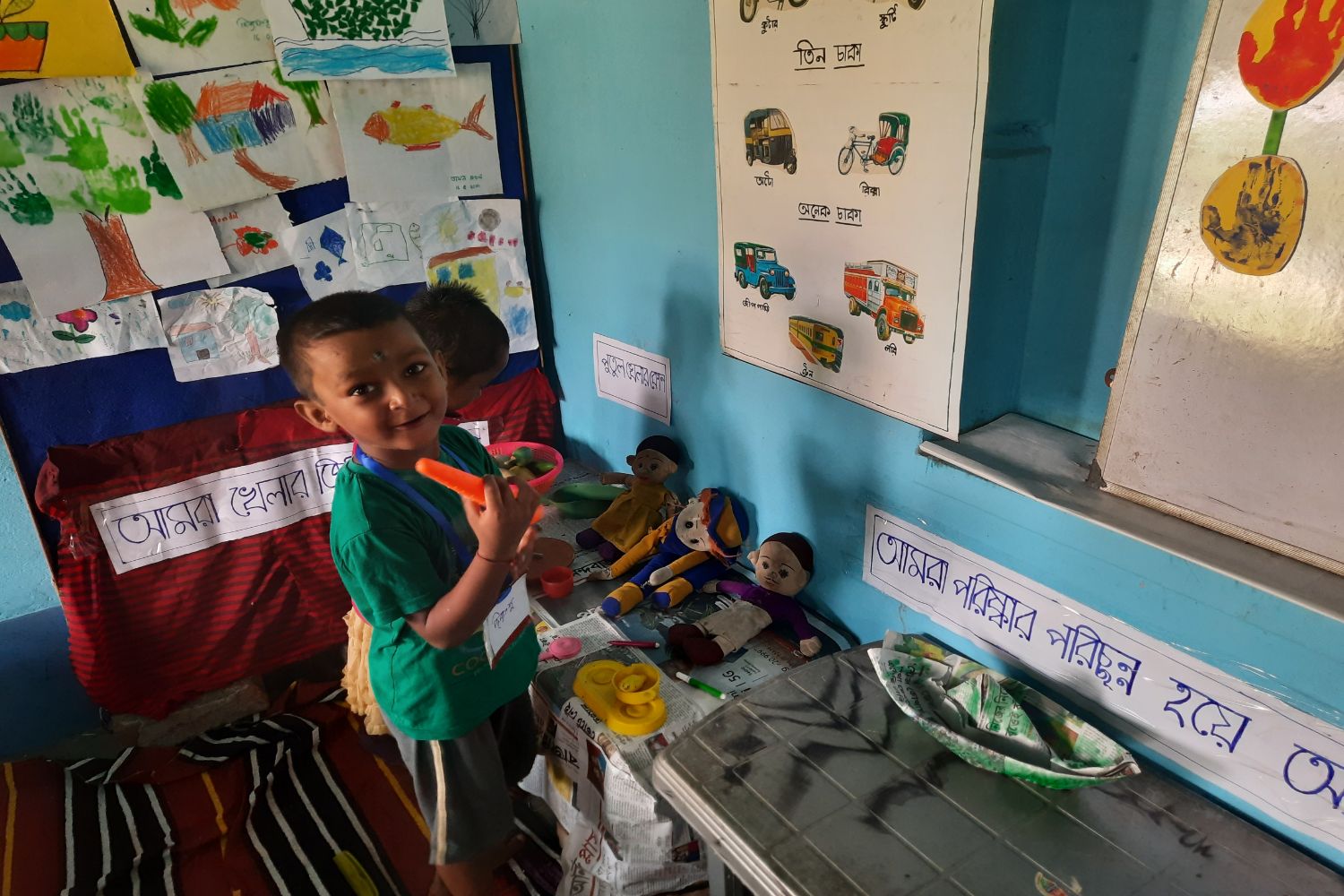

The program of study lays explicit emphasis on development of practical skills. Almost 40% of the course is dedicated to hands-on experiences and internship. With 32 credits in total, 18 focus on theoretical knowledge, while the remaining credits are allocated to field-based experiences.

Students have the opportunity to work directly with children in preschools, engaging in activities for 30 working days. They also complete home-based practical activities. These experiences allowed learners to observe children’s development, design balanced diets, and interact closely with families, nurturing their skills in real-world settings. The program strikes a careful balance between theory and practice. It, thus, ensures that graduates are well-prepared for the demands of the field.

One aspect that we always took great care of was to include real-life examples of children, showcasing their development, abilities, thinking and activities. These were not fictional scenarios but real-life instances that we had encountered, observed, or heard about. We captured these moments and integrated them into the course materials to provide tangible and relatable contexts. By connecting theory with everyday observations of children, we aimed to make the content more engaging and accessible for learners.

As an academic offering, these unique features truly set our program apart. The program garnered positive recognition. It even surprising us when renowned educators commended its well-written materials during conferences. It was a testament to the quality and impact of the program.

Vikramshila: What were the enrolment patterns for the ECCE diploma program, particularly in relation to the gender distribution and regional participation? Was there any impact on the perceptions and motivations of learners regarding job opportunities, considering the lack of official recognition for diplomas obtained through Open and Distance Learning (ODL) mode?

Dr Rekha Sharma Sen: After the initial years, the enrolment in our program stabilized at 3,000 to 4,000. In 2019, we experienced a significant shift in enrolment patterns for the diploma program, which had a direct correlation with the growing importance of ECCE in the education system. It was remarkable to see a massive enrolment from Punjab, and enhanced enrolment from Odisha, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan. Delhi always had a high enrolment pattern.

We learnt that in Punjab, the government was planning to open up nursery sections in all schools. While we never received an official letter from the Punjab government regarding job opportunities, there was a perception among learners that completing the ECCE diploma would increase their chances of being considered for teaching positions. The implementation of regulations for private schools in certain states such as Himachal Pradesh and Maharashtra also appeared to have a positive impact on our diploma, as learners sought to obtain qualifications.

The changing dynamics of enrolment had both positive and negative implications. On one hand, it created a more balanced gender distribution, with almost an equal percentage of men and women enrolling. Prior to 2019, the program had been dominated by women, but that started to change. Additionally, the urban-centric nature of the program also changed with learners enrolling from rural areas.

In 2016, before ECCE gained nationwide recognition that it has now, I conducted a study to explore the motivations of learners for joining the diploma program. I found that learners joined with varied motivations. Some learners were already working in the sector of ECCE. They sought to upgrade their qualifications. This was either because they lacked any formal qualifications, while others were encouraged or even required by their employers to obtain this diploma as its course content was seen to be of good quality. Some learners reported that though they had an ECCE Diploma from some institution, their employers demanded that they complete this IGNOU Diploma.

A surprising group of learners were those who had no prior experience in ECCE. They were in fact from different fields such as computers or management. They were motivated to enroll in the ECCE program, as they wanted to change their careers due to a variety of reasons, and saw ECCE as a suitable and interesting career. These two categories of learners were very satisfied with the program outcomes. They agreed that the course material provided valuable insights and knowledge, rather than simply being a set of activities.

Another group of learners I observed were young individuals who were primarily focused on securing a job. However, the outcome for these learners had both positive and negative aspects. Many of them pursued the ECCE diploma with the hope of getting a job. However, they were often left disappointed. Although the program holds immense value in terms of quality materials and content, there is no official recognition from accrediting bodies. Neither do recruitment rules for employment in the government sector, specifically include qualifications obtained through the Open and Distance Learning (ODL) mode.

In 2014, a committee, chaired by Professor Venita Kaul, was formed to establish ODL norms for teacher training diplomas. Recommendations were submitted to the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE). Unfortunately, no significant progress was made. Currently, there are no established norms for offering distance education courses in the field of teacher training. As a result, the ECCE diploma obtained through ODL is not considered legitimate for employment in the government sector.

As a consequence, these learners who pursued the ECCE program with the goal of securing jobs now mostly aim for opportunities in the private sector. It is worth noting that the private sector often offers lower salaries and may not provide the same level of stability as government positions. Interestingly, a significant portion of the learners engaging in the program immediately after completing their 12th-grade education falls within this group.

My study from 2016 provides valuable insights into motivations that may still be relevant today. However, I believe that conducting a similar study now may yield different responses due to the current landscape where ECCE has become the sought-after choice for many individuals.

Vikrasmshila: We’ve heard that IGNOU is developing a certificate course on ECCE. How was this conceived? How is this offering unique compared to the diploma course?

Dr Rekha Sharma Sen: Yes, we have devised a six-month certificate program in ECCE. The conception of this program took into consideration the need for a more practical approach to education, with less emphasis on theoretical content. What makes this program unique is that it is aimed at individuals who are already working in the field and wish to upgrade their knowledge and skills.

The program directly caters to the requirements of the 3 years of preprimary education, addressing the need to differentiate activities for different age groups within this range. It focuses on distinguishing activities appropriate for the 3-plus, 4-plus, and 5-plus age levels. For instance, it will help to understand what music or art activities at different levels of pre-primary education can be conducted, i.e., pre-primary level 1, pre-primary level 2 and pre-primary level 3. This aspect sets it apart from the diploma and postgraduate diploma programs.

Another notable feature of the certificate program is the emphasis on self-exploration and the use of a learning journal to document capabilities and skills. In contrast, the diploma program involves a more formal assessment process, where learners working in preschools submit project files for evaluation at IGNOU. With the certificate program, learners will be encouraged to submit their learning records, including activity recordings, at their own local centres. This process aims to promote a decentralized assessment approach that considers the specific contexts and needs of the learners.

The content and assessment procedures of the certificate program will differ based on the specific course objectives. The target audience for this program primarily consists of individuals already working in the field. However, it is open to anyone interested, as there are no restrictions on enrolment. It is expected though that learners entering the certificate program would have some prior experience or understanding due to their working background or previous training.

Vikramshila: Based on your experiences, what are your recommendations to the states who are looking to improve their capacity building programs?

Dr Rekha Sharma Sen: It is important to address the learning loss that may occur in the cascade model of training, where master trainers train subsequent trainers, resulting in a potential decrease in quality as information is passed down. There should be more extensive handholding and support provided at the grassroots level by academic institutions.

Sustaining the motivation of teachers is another crucial aspect. Both the public and private sectors face unique challenges. We demand more and more of the teachers. But have we put into place systems that reward them? This includes implementing systems that recognize and reward their efforts, tailored to the specific contexts of each sector.

In India, where supply often exceeds demand, there is a tendency to neglect worker motivations, assuming that someone else will fill the role at the same level. However, this approach leads to wastage of capacity, time, and training investments. Neglecting motivation can lead to wasted capacities and training efforts.

Considering the significance ECE has gained, it is vital to focus on the quality of training programs. This may involve establishing a national-level body, independent of existing organizations, to assess and accredit different training models. Streamlining and recognizing various training approaches and their unique features would provide a more comprehensive understanding of their efficacy.

Increased supervision is crucial for ensuring effective implementation. Based on my experience of working with ICDS, and the pilot testing of the restructured PSE curriculum through a study in 2013, we found that the involvement of supervisors played a significant role in improving outcomes. The findings of the national level report were significant, as almost everyone observed that an enhanced curriculum and improved training had a positive impact.

I remember the phase when these changes were implemented, as there was increased Vikramshila supervision by the supervisors. This led to a stronger sense of connection and a feeling of support among the Anganwadi workers.

They experienced a boost to their self-esteem, when community members started referring to them as ‘teachers’ rather than as just ‘workers.’ When the three levels of staff—the Anganwadi worker, Supervisor, and CDPO—worked together in sync and received adequate support, we witnessed excellent outcomes. The time allocated for implementing preschool education activities, especially the 2 and a half hours devoted by the Anganwadi worker, played a crucial role.

It is essential to prioritize freeing up their time or providing additional support, such as another Anganwadi worker, to fully realize the benefits of training. Merely having the motivation and training isn’t enough, if there’s a lack of time or supervision to execute the desired tasks. It’s unfair to burden Anganwadi workers alone with the responsibility of non performance.

Instead, they should be empowered and supported to perform at their best. Ultimately, the responsibility for addressing low performance lies with those higher up in the hierarchy. We must find ways to enable the individuals we supervise or work with to excel.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!