Funding strategies, convergence challenges and advocacy for ECCE policy impact

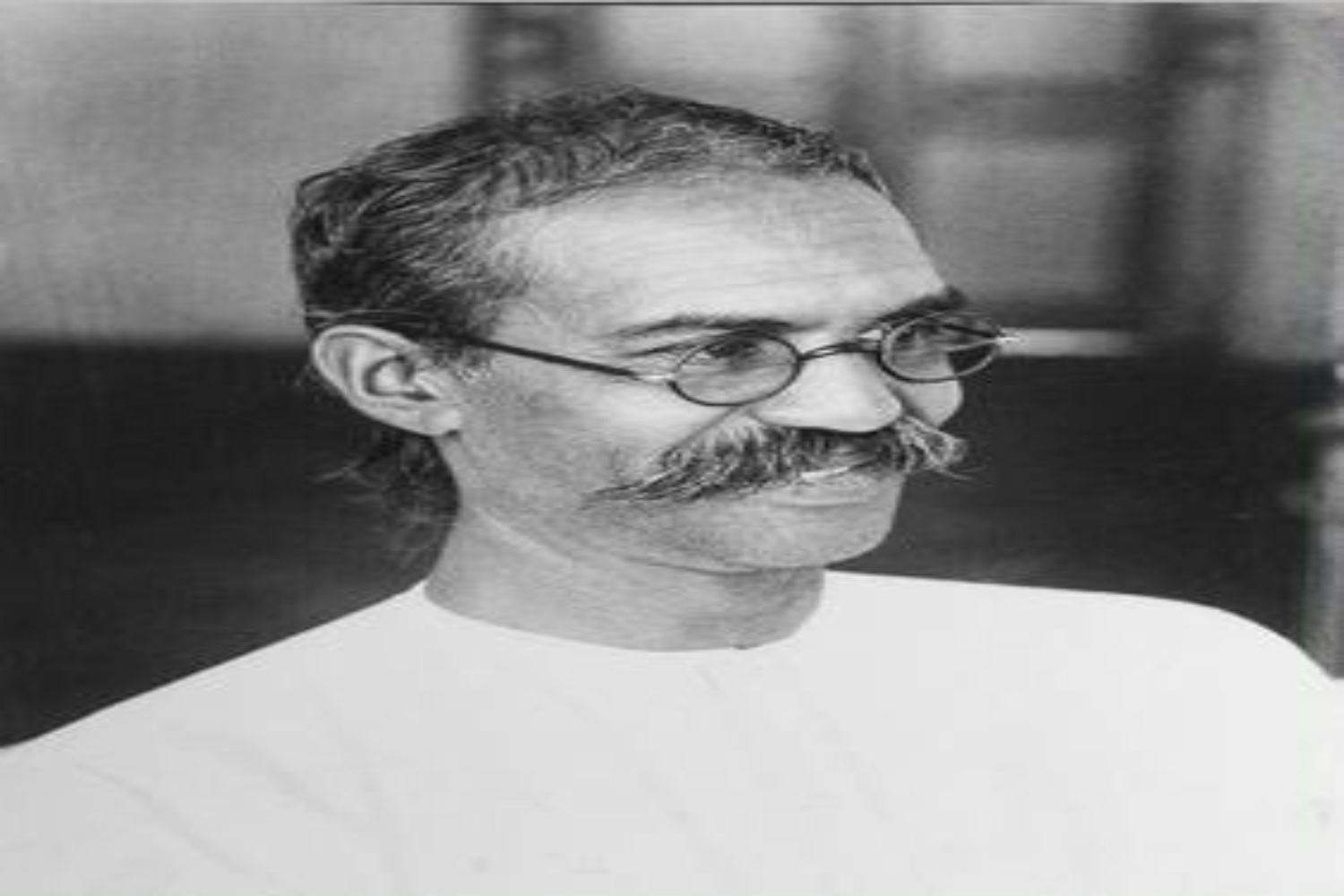

In this interview, Dr. Jyotsna Jha provides insights and guides to practice on funding strategies, convergence challenges, and advocacy for ECCE in the ECCE space.

Dr Jyotsna Jha currently heads Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, Bengaluru. She has led a number of research initiatives and co-authored books.

She has also contributed to literature related to equity in education, gender, women’s empowerment and public finance. In recent years, she has worked on a wide range of public policies and finance issues.

These include gender budgeting, health finance and public spending on children. Before that she has worked with various governments and CSOs (civil society organizations) on issues of equity in education.

Vikramshila: National Education Policy (NEP 2020) confirms India’s commitment to the SDG 4.2 of universalizing Early Childhood Education (ECE) by 2030. To achieve this goal, substantial financial investment is required. What strategies can the governments employ to secure the substantial financial investment required to achieve the goal?

Dr Jyotsna Jha: Although Early Childhood Development (ECD), which includes health, nutrition and education, has received great attention in the education policy, we still don’t have a framework, which lays down each department’s responsibilities and how they are supposed to collaborate in order to achieve the goals of NEP 2020.

We have to work with three departments — women and child development, education and health. It would become more efficient and easier if we have a conceptual clarity and know the role of the respective departments.

When we talk about ECD, we solely focus on children’s rights and overlook the rights of adults, such as Anganwadi workers and teachers. Our efforts should be directed towards protecting the rights of all individuals. In this regard, the presence of a comprehensive framework becomes critical.

Coming to estimation of financial requirements, they cannot be determined without well-defined physical and financial markers. However, such markers and figures can only exist if there is a framework in place.

In the past, we focused on developing a framework that emphasized the protection of rights for all individuals involved. It is crucial to consider the rights and well-being of teachers, caregivers, and other personnel involved in the delivery system. They should be treated with respect and provided the necessary protection and support to fulfil their roles effectively.

It is evident that inadequate compensation and poor treatment can negatively impact dedication and willingness to perform at their best. Therefore, training programs and improved remuneration are essential to foster better performance, and ultimately ensure the rights of the child.

In terms of early childhood education and nutrition, our framework extends beyond mere access. It emphasizes the need for age appropriate, comprehensive education that aligns with existing knowledge and global standards. In our framework, we have four key pillars: protection of rights, accountability, sustainability, and flexibility.

Let’s delve into the aspect of flexibility. When considering urban areas, it becomes apparent that existing rent norms and the growing population in cities pose interconnected challenges. The city-centric development model exacerbates the premium on real estate and rents, making it difficult to provide adequate space. Several studies have highlighted this constraint in urban settings, calling for flexible norms, particularly in rent regulations.

Besides, cost estimates vary based on flexibility and the differences in prices across locations. Cost estimates will vary according to locations. But that doesn’t mean that the quality of service is different. For instance, the prices in Mumbai will be higher than those in rural areas. But if we have a framework, which takes into accounts these difference in prices, then making allocations will become easier. Stakeholders will have clarity on the costing estimate.

Determining the exact investment in early childhood development, including education, remains challenging due to varied expenditures by the Central and State governments. Nevertheless, it is estimated that the required investment may be three to five times higher than current allocations from the Central and state budgets.

Regarding resource allocation, collaboration with institutions such as universities, government buildings, and unused physical spaces in urban areas can help optimize resource utilization. Philanthropic involvement can also be encouraged once the costs are established. Additionally, streamlining the allocation process and leveraging technology can enhance efficiency and reduce redundant parallel surveys. Creating a citizen-centric database accessible to officials at various levels can contribute to better decision-making and resource allocation.

Moving forward, it is essential to identify potential sources of resources. This requires a comprehensive examination of available funding options. Engaging with stakeholders, including government bodies and NGOs, can help identify innovative funding mechanisms. By exploring various avenues, we can secure the necessary resources to support early childhood development.

Vikramshila: What steps are being taken by the state governments to ensure that the additional funding required for ECCE is allocated and utilized efficiently? Can you give some examples based on your experience?

Dr Jyotsna Jha: Yes, I think several southern states in India, as well as Maharashtra, have been allocating additional funds for ECCE. For instance, Karnataka spends more than it receives, with its contribution to the union being higher than what it receives in return.

There are various schemes and initiatives implemented by state governments such as Maharashtra, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu. They have extended hours, social security and retirement benefits for Anganwadi workers. Therefore, perhaps, Government of India (GoI) needs to extend more support to states which have not been able to spend enough on ECCE.

In one of our comparative analyses, we have observed that in certain states issues such as privatization and the need for better regulatory frameworks were identified. However, it’s important to highlight that there are also positive examples where states have recognized the significance of nutrition and education and have shaped policies accordingly. They have taken significant steps towards integration and addressing various issues related to early childhood education and development.

Vikramshila: Within the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) program, which includes ECCE, health, and nutrition services, how can convergence between these programs be achieved? How will the NEP’s placement of ECE under the education department impact this convergence?

Dr Jyotsna Jha: I am wary about the integration of Anganwadi centres with primary schools for several reasons. One concern is the downward shift of expectations, where early childhood centres are pressured to prepare children for school admissions.

Even though admission tests have been made illegal, the reality is that preparation for admissions still occurs. Government schools also expect children entering class 1 to have prior knowledge of letters and numbers, creating a burden on early childhood centres to focus on rote learning rather than holistic development.

Another issue, I have observed, is the power relationship between schools and Anganwadi Centres. I don’t see a relationship of equality, although I see a lot of space for cross-learning. How can that happen if one is not open? A teacher who receives higher compensation will be disinclined towards learning from an Anganwadi worker, who earns a much lower pay, even if they are equally educated. This power hierarchy has to be broken.

There is a third concern with regard to women being unable to leave their children, especially those aged between 0-3 years, as Anganwadis are yet to function as proper creches.

While there have been attempts to bring about change in education, certain factors impede progress. Our search for measurement and learning outcomes sometimes undermines the quality of education. I recall an experience shared by a young professional who witnessed a stimulating classroom discussion in class 2 on water conservation since the school was facing water crisis.

This was disregarded by an observer at system level, focused solely on meeting competency checklists as per NIPUN Bharat Guidelines. Consequently, a report was submitted emphasizing the shortcomings of the class. I hope that we can move beyond these challenges and work towards creating a more holistic, inclusive, and child-centric education system that nurtures creativity, critical thinking, and overall development.

Vikramshila: How can research be used to support policy and budgeting decisions for early childhood education? What specific types of research can civil society organizations (CSOs) conduct to ensure a strategic and effective financial outlay?

Dr Jyotsna Jha: I firmly believe that if all CSOs unite and agree on a common framework, we can effectively influence change, even though there may be minor differences in our approaches. This framework can serve as a guideline, allowing flexibility and adaptation.

There can be several spaces that can be used for advocacy. One has to build public opinion and mobilize the middle class and gain their support. Only then we can expand our network of advocates. Collaboration allows us to work simultaneously in different areas, such as cost, budget analysis, and classroom practices, amplifying the impact of our efforts.

For instance, the organization Haq was at the forefront of introducing the concept of a child budget in India. While they had their specific approach, we began working with Karnataka budgets and took a position that the existing approach was inadequate. Slowly, it got noticed. Today, we are hoping the possibility of collaborating with the Ministry of Finance, to advocate for a different budgetary approach that incorporates our insights.

Our efforts have led to invitations from certain states and resource agencies. We have been actively involved in these endeavours since 2014. Over the past decade, we have witnessed a noticeable movement taking shape. It’s worth noting that despite not being a particularly powerful organization, strategic collaborations have allowed us to access influential positions and institutions.

Open communication, active listening, and a shared framework are key to achieving the goals of NEP. We all face constraints and sustain our work through various projects. Yet these limitations should not hinder our capacity for innovative thinking. It is possible for us to establish a position that garners widespread consensus and seek funding through various avenues. By consistently working towards our shared vision, we can strive for a responsive government that aligns with our goals.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!