Nature education as a conservation tool: a personal narrative from Kas Plateau, a UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site

In this issue, images from nature education interventions carried out by Prerna Agarwal in Maharashtra.

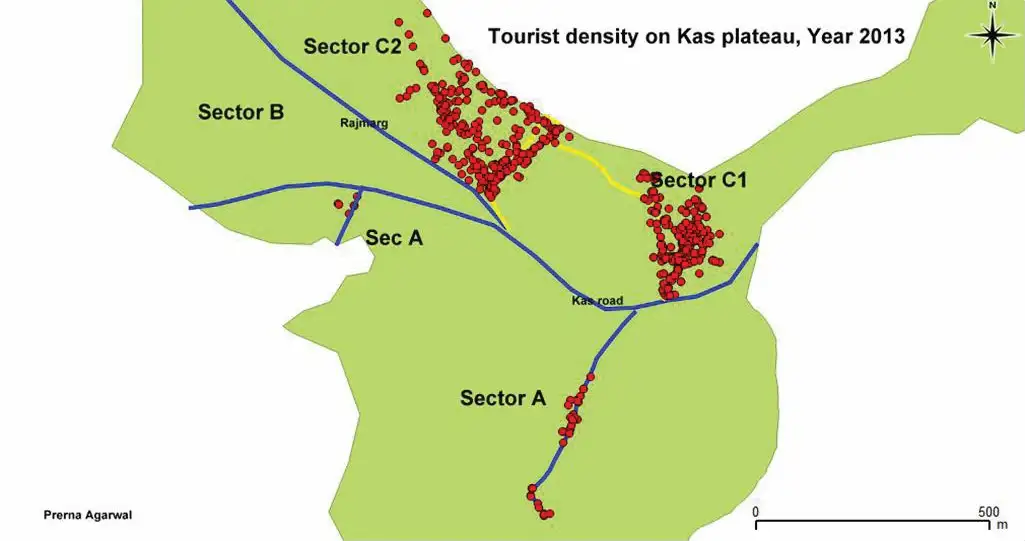

Come monsoons, and the carpet of wild flowers attracts thousands of visitors every year to Kas plateau, a UNESCO natural World Heritage Site, situated in the Western Ghats of India. A place of astounding botanical significance, this rocky plateau supports around 250 flowering plants, with mind boggling adaptations – carnivory, parasitism, desiccation tolerance – to survive this habitat of extreme environmental conditions that spares no one. Interestingly, many of the plants are endemic to this region, which means species found nowhere else in the world! This place of ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ changes colour every few weeks in the monsoon season. However, all was not well with Maharashtra’s wild flower paradise when I started working as an independent researcher in 2012. This ecologically fragile area faced a serious threat from mass tourism. Habitat destruction due to unregulated visitor movement, vegetation trampling and traffic congestions were the major threats.

July

plant (Utricularia purpurascens) and white (Eriocaulon

sedgwickii) in August-September

The various threats due to mass tourism faced by Kas plateau in 2012 when the author began her work.

This photo story will take you on my personal narrative of how as an Inlaks Ravi Sankaran Scholarship fellow in 2014, I experimented with various nature education tools to sensitize tourists and local communities to conserve the natural heritage of Kas plateau.

In the initial phase of the project, a series of meetings were conducted with the Maharashtra Forest department officials and Kas plateau Joint Forest Management Committee (JFMC) members, to plan the project through stakeholder participation. Through these discussions and my own observations, the key on-ground challenges identified were: 1) Lack of well-trained guides to meet the growing demand; 2) Visitor sensitization regarding the uniqueness of the plateau through well designed signages in Marathi as well as in English; and, 3) Absence of designated paths to regulate visitor movement in order to reduce vegetation trampling.

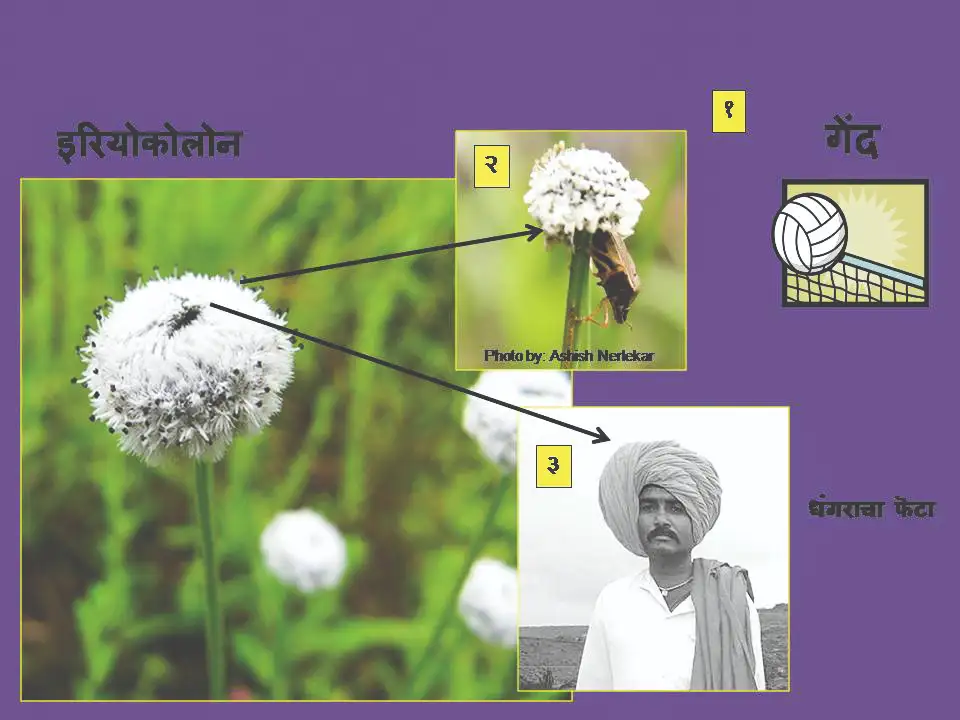

To bridge these gaps and to design effective outreach material, I first spent a few months understanding the traditional ecological knowledge of the various plants found on the plateau. I realized that the local names of plants used at Kas (though these were in Marathi too) were different to those used popularly by the botanist/naturalist community. I kept jotting down these names as and when I came across anything new.

On one such exploratory adventure, I was invited to attend Ganesh Puja at a beautiful scenic village called ‘Kaasani’ at the foothills of Kas plateau. I could not have thanked my hosts enough for having invited me to the village at that time of the year. This was the first time I experienced Kas plateau’s local culture. Right from making a mini model of the plateau as part of the Ganesh festival decoration, to using a balsam flower species called ‘Gauri terda’ as an offering, to worshipping the purple coloured Bharangi flowers (Rotheca serrata) as an avatar of Lord Shiva.

That day, as I saw these cultural practices first-hand, I felt I needed to change the narrative of ‘nature experience and outreach at Kas’ from a pure ecological one to one that was more inclusive by integrating the cultural stories this landscape was brimming with. Once the visitors would read these stories, I thought they would feel more connected to the landscape, rather than being bombarded with just botanical names. The idea was also to instil a ‘sense of pride’ towards this UNESCO natural heritage site in both the local communities and in the visitors.

Finally, all the information collected during 2012-2014 was compiled in a pictorial booklet as a tool to be used by the guides while conducting tours in the area. The guides suggested that we keep the paper size large so that they can show the flower images (which are otherwise quite miniscule) to large groups. The paper size thus chosen was A4 and every page was laminated to make it waterproof. Additionally, the botanical names were written in Devanagiri script to enable the guides to use these technical terms.

“The booklet is very useful for me. In addition to showing enlarged images to the group, I use it as a revision tool at the end of the tour. I flip through the pages with my group to revise all the plants they see. Also, the booklet acts as a truth proofing with the tourists. When they see that I am saying the same names as mentioned in the booklet, they become more confident about the information I am providing them.” said Ashok Kurale (a local 35 years old guide and a JFMC member). Another senior guide Dhondiba Aatale, who is 75 years old, mentioned, “I cannot read. So the booklet that was given to us was extremely helpful as it was pictorial.” The guides found this booklet extremely useful, and requested to include photographs of butterflies and birds included in it too. We brought out a revised version with these additions.

Nature guide training

In addition to the booklet, a two months long guide training program was conducted which included soft skills training too. To objectively assess the success of the program, a pre and post test was conducted. Most guides scored higher in the post test, and gave positive feedback for the training program. The guides said that the mock tours helped them gain much needed confidence.

“I start my tour with an introduction. Then, I ask the visitors from where they have come. I check with them their interests. I first see what their interest is. Accordingly, I conduct the tour. I do not mention the ‘Dos and Donts’ in the beginning. Instead, whenever I see someone go off the path, I ask them to stick to the path and inform them that if the flowers are trampled, they will not grow back,” says Sopaan Bhosale, a 40 years old guide who conducted 10 trips in 2014.

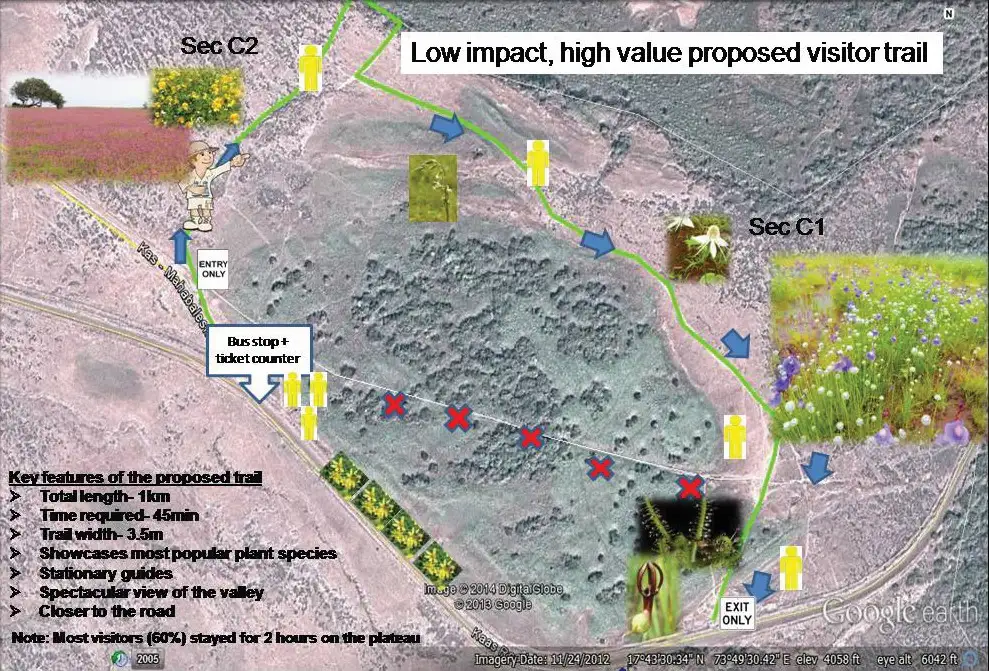

The high value low impact trail

In an attempt to regulate tourist movement in the main tourism zone, it was proposed to demarcate an informal (~5 feet wide) trail on an existing path. Visitors were encouraged to use this path by strategically placing signboards and having stationary guides who acted as guides as well as guards. Most plant species preferred by tourists could easily be seen along this trail. Hence, it was proposed as a ‘high value low impact trail’.

Open interpretation center

An open interpretation center was developed on an experimental basis by installing 24 boards, out of which six boards provided awareness messages using local deities, e.g., take the blessings of Kasai Devi by walking only on the path. Fourteen boards were information boards of different plant species, and four boards were of maps of the plateau showing different trails open to the visitors. All boards were in English as well as in Marathi. The earlier boards were either only in Marathi or entirely in English, thus limiting their audience. The 24 boards were put up at strategic locations on the plateau.

After seven years, today, the management of Kas plateau has improved significantly, thanks to the sincere efforts taken by the Satara Forest Department and the JFMC members. However, newer challenges of visitor management continue to crop up.

In my experience from Kas plateau, I feel a diverse set of nature education tools have to be used rather than focusing on only one kind to connect with a range of stakeholders. Nature tourism is a double edged sword. Only by evolving with the changing times and through innovative, locally-relevant ideas can nature education serve as a powerful tool for nature conservation.

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to thank the Maharashtra Forest Department for the necessary permits, the Kas JFMC for help in carrying out this work, and the Inlaks Ravi Sankaran fellowship for funding support.