A children’s home context in education

Akash (name changed for privacy) was placed in a Child Care Institution (CCI) in Kandhamal, Odisha, by the district Child Welfare Committee (CWC) on the request of his maternal aunt. His mother was arrested for physically assaulting her alcoholic husband to protect their son. The seven-year-old was confused, overwhelmed and scared in the unfamiliar environment. […]

Akash (name changed for privacy) was placed in a Child Care Institution (CCI) in Kandhamal, Odisha, by the district Child Welfare Committee (CWC) on the request of his maternal aunt. His mother was arrested for physically assaulting her alcoholic husband to protect their son. The seven-year-old was confused, overwhelmed and scared in the unfamiliar environment. This made the child reticent and uninvolved in the activities that the CCI conducted.

The CCI Superintendent noticed that Akash only spoke Kui. It is a south-central Dravidian language spoken in Odisha by an indigenous Adivasi community. The Superintendent asked Catalysts for Social Action (CSA) to intervene, as one of the tuition teachers, Bijaya, knew Kui.Bijaya assessed that Akash was able to read and write alphabets and numbers in Kui, as he regularly went to an anganwadi back home.

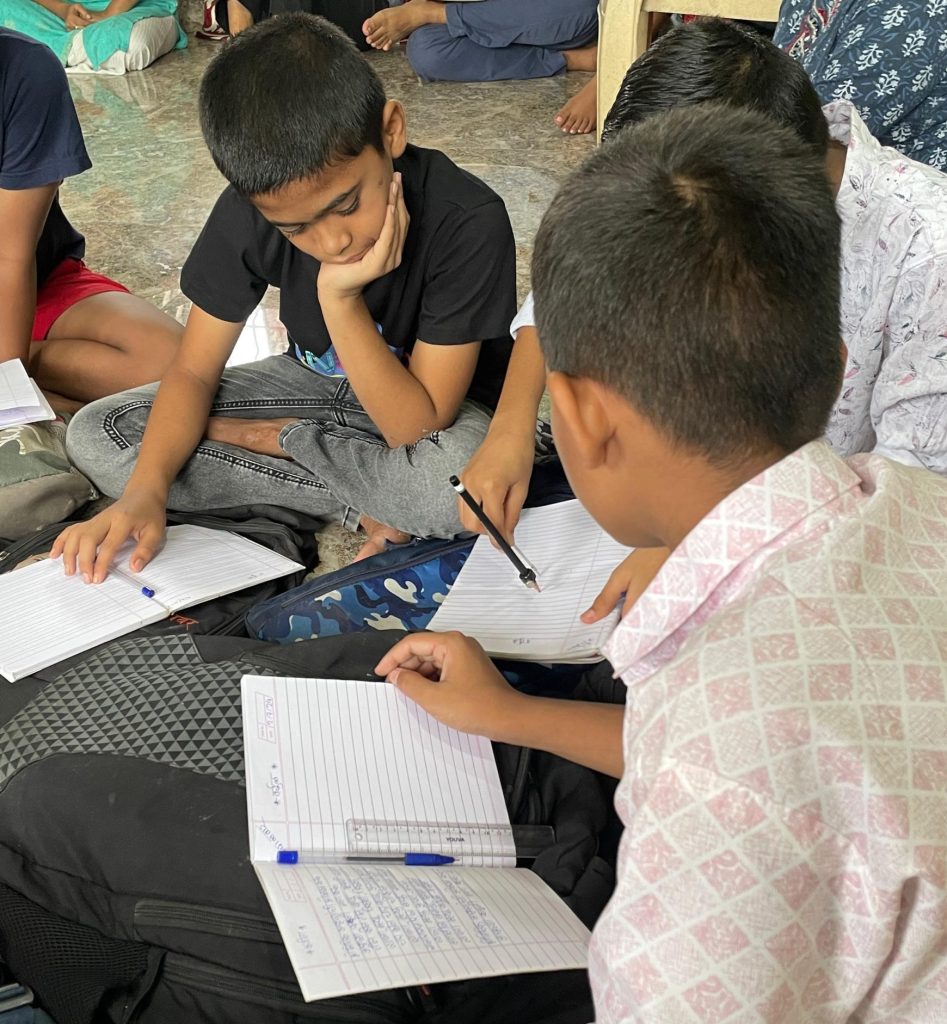

Bijaya explained, “Akash was feeling isolated because of the language barrier. So, I introduced him to eight-year-old Lalita, who also spoke Kui. They started studying together. This is called ‘peer learning’. This strategy is used by many educators in similar situations. Here children learn from each other. They get new perspectives and have increased social interactions. This leads to deeper personal learning for both the children. We have found peer learning to be very effective for children in CCIs.”

Akash and Lalita became friends. She played number games with him and shared stories that were introduced by Bijaya. It has been six-months since Akash entered the CCI. He has been going to a local government school with other children. Bijaya reflects on peer learning to be an effective decision that brought about a change in the child’s personality.

CCI: a home away from family

CCIs are residences where children like Akash are placed for their care, protection and rehabilitation, when their parents are unable to take care of them. So, the children here may be orphaned, abandoned or surrendered by their parent(s). Or, they may have been rescued from a situation of abuse and neglect. They may also have been placed in an CCI because their parents are unable to care for them. Some of these children are those who are alleged or found to be in conflict with the law.

Their period of stay in the CCI could range from a few days to years. This depends on their own needs and family situation. The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, which governs the functioning of CCIs, requires them to provide developmental and rehabilitative services to children, including education and health.

CSA works in partnership with government and NGO-run CCIs. Most of these CCIs are in rural and semi-urban locations across Odisha, Madhya Pradesh (MP), Maharashtra and Goa.

A child has to first feel safe

When a child enters a CCI, it is often with trauma, experiences of abandonment or neglect. These children have often lacked a consistent adult caregiver in their lives and have undergone disrupted schooling.

In such cases, learning can’t be restricted to academics alone. It is imperative to first identify children’s emotional and psychological needs. These may be different from that of children who live with parents. A child cannot learn unless they feel safe.

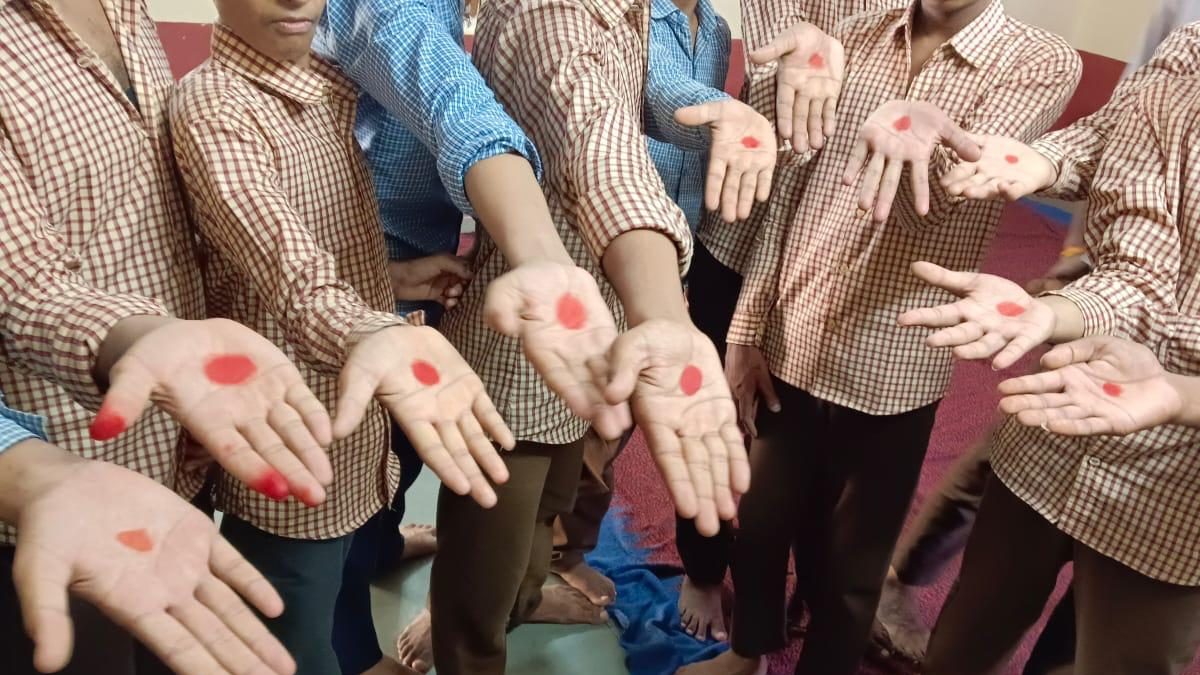

So as part of holistic development, children participate in a variety of activities. Their goal is to make them feel safe and foster a sense of belonging. Most mornings are about yoga. Enough time is allocated to sports and physical fitness in the evenings. Children engage in art, craftwork, listen to stories, and experience circle time. Wherever possible, they even grow their own fruits and vegetables in kitchen gardens.

CSA’s program officers conduct life skills, adolescent health and child safety sessions. These aim to add to the children’s socioemotional well-being. These sessions encompass physical activity, personal hygiene and self-care, healthy relationships and communication, societal gender view, and sexual and reproductive health.

Some of these sessions have been game changers for children. Sameera (name changed for privacy) faced repeated sexual abuse by her stepfather every time her mother went out to work as a house help. After seven months of the ordeal, the child broke down and confided in her mother. The man was reported to the police. However, he was soon let out on bail. The mother then admitted the 12-year-old to a CCI in Maharashtra to protect her.

Sameera was deeply sad to be away from her mother. She would blame herself for the trauma she experienced. She felt very anxious and intimidated. She used to go to school before entering the institution. However, after entering the CCI, she completely withdrew from studies and used to remain aloof.

CSA’s tuition teacher Kamini, who would visit the CCI every day, observed this. She tried to include her in all the activities and games they played to learn math and language. After attending sessions on adolescent health and safety, Sameera learnt about her body. She began to understand the abuse she went through. She also started opening up and expressing herself.

It may take a lifetime to overcome such trauma. However, the attempt is to make children speak up and absolve themselves of the shame, guilt and blame that is typical of such situations. Once the children are engaging with others and start participating in activities, the learning process can continue.

Holistic and integrated learning

A lot of hard work goes into making children experience as empowered a childhood as possible. So, children are taken for outings – to zoos, museums, heritage sites, parks and even cinema halls. This helps to ensure that they are growing up just like the other children they meet in school.

Every CCI has a Children’s Committee. It is an elected representative body advocating for children’s rights within the CCI. The committee meets regularly to discuss and take decisions on the problems the children may be encountering. It also tries to identify productive ways for the CCI to function.

These meetings are minuted and become the bedrock on which democratic values are built in children. Such committees are mandated by Rule 40 of the JJ Rules, 2016, as amended in 2022. The objective is to gather insights into the CCI’s daily activities and foster a sense of responsibility, nurture leadership qualities, and bolster self-confidence to express opinions.

Weaving in different skills into one integrated whole is a skill CCIs are slowly developing. For instance, computer labs are set up in some CCIs where children are allowed to play around with the computers. They are taught by appointed computer teachers as well.

Children receive certificates for basic, advanced and other specialized courses. Once they get familiar with the workings of the computer, they start maintaining the minutes of Children’s Committee meetings on the system itself. They also start teaching the younger children how to operate computers.

The challenges

Institutional care is meant to be a measure of last resort. Every child, by right, deserves a loving and nurturing family environment. So, children in CCIs may either be restored to their biological family or placed with adoptive/foster families by the CWC, as soon as possible. This depends on their needs and situations. From a teacher’s perspective this poses a challenge, as the children are a floating population.

Abinash Jena, Location Head – Odisha says, “Due to changes in the children’s numbers, it becomes difficult for teachers to follow a schedule with them. A child may enter the institution with considerable learning gaps. The other children their age may be at a different level. The teacher puts in a lot of efforts bringing the child up to speed. But they often find that the child gets deinstitutionalized soon.”

Grouping a floating population of children is often an onerous task. Sometimes children go back home during vacations or for short durations. They then come back with ‘vacation-loss’ and/or separation anxiety. Specific life skills sessions try to ensure that the child is re-oriented, feels safe, and then learning is re-bridged.

Listing out another challenge, Lucy Mathews, Head of CCI Operations, talks about multigrade, multi-level teaching. “A CCI has children studying in different grades, sometimes going to different schools, are on different stages of the curriculum at school, and are of different learning levels as well. A tuition teacher has to deal with this complexity. Typically, tuition teachers spend two-hours every day with the children. Dividing their time, so that each child gets some individual attention, is a big challenge.”

Here, what helps is when we group children in a way that they can teach and learn from each other. Sometimes, older children are made to teach the younger ones. This helps make concepts sharper for the older children.

Children like Akash and Sameera growing up without their families can gain a lot with the village coming together to raise them. Likeminded CSOs like Khelghar, Eklavya, Patang, Peepul, Bookworm, and Dream a Dream, are all helping create this village, so that every child learns. And even though Akash and Sameera can’t be with their families, they receive family-like nurturing care.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!