A new future for the knowledge generation– citizen science

This article discusses what is at stake in doing citizen science.

While walking with Joel Mathew, a fourth-year undergraduate student at the National Institute of Science Education and Research (NISER) campus in Odisha, one is likely to see the iNaturalist app open on his smartphone. “I love using iNaturalist to identify flora and fauna around me,” he says. When asked about why he uses iNaturalist, he shares, “I love that I can create projects on this app and quickly share rare observations with others. The option to comment under each observation helps me communicate with the entire citizen science community in one go!”

iNaturalist is a biodiversity citizen science project. It is one of many in the world. It primarily documents biodiversity through images.

Scientific research conducted by nonprofessionals or amateurs is known as ‘citizen science’ (cit sci). This often involves the collection and curation of information about the natural world.

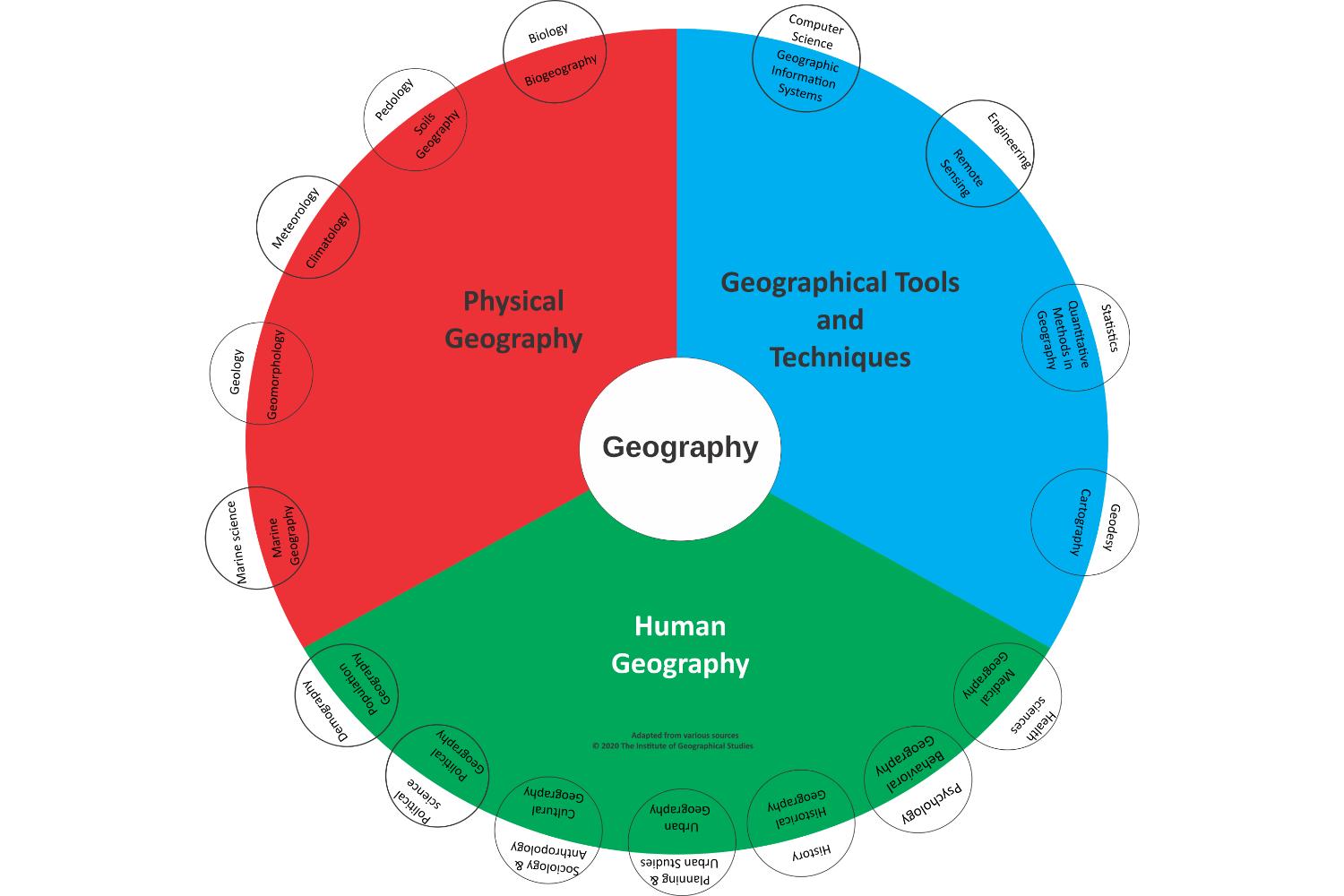

Citizen science empowers people to cocreate scientific knowledge for the benefit of the larger society. It takes science from the jargon-filled pages of journals to the fingertips of practitioners and users of this information. Today, citizen science encompasses a wide range of disciplines. These span from monitoring climate change and tracking disease outbreaks to crowdsourcing astronomical discoveries. It plays a vital role in increasing public engagement with science, enhancing research capabilities, and democratizing knowledge creation across the globe.

Non-professionals have long collected data about the natural world. This is in no way a recent practice. Humans are curious and exploratory by nature – as we should be – since this is vital for survival in the natural world. Curiosity, documentation and experimentation is how humans knew so much about growing food, tracking weather, geography and astronomy, even before these became branches of intense scientific enquiry.

Take the case of the iconic Japanese Sakura tree, for instance. In current times, it has become the poster child of changed tree seasonality because of climate change. It is a culturally important tree, which has been observed and recorded in informal ways since 800 AD!

Thanks to 1,200 years of records of its flowering chronology, we now know that the climate has most certainly changed after the industrial revolution. This reflects in the tree flowering much earlier in the past 200 years than in the millennium before that. Among the different ways of observing the natural world, documenting biodiversity lends itself particularly well to citizen science. Some of the earliest documented citizen science projects – such as the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, which began in 1900, documented bird densities.

Non-professionals have for long assisted professional scientists, especially with the exploration of the natural world. In the 18th and the 19th centuries, naturalists and astronomers utilized the skills of local guides and amateurs to identify and collect species for description, and map stars, respectively.

The term ‘citizen science’ came into being only in the later decades of the 20th century. With increasing access to the internet and simple observation protocols, citizen science has truly taken off in the past four decades across the globe.

Changes in the way people live and interact with their environment have additionally created a ‘nature deficit’, where there is little to no opportunity to engage with living beings other than humans. Unbeknownst to us, this deficit has gradually created a vacuum in our well-being. Biodiversity citizen science is an opportunity to spend time outdoors and observe living beings, and marvel at the beauty of the interconnectedness of life.

Handheld technology, widespread training, support and troubleshooting, and access to the skills of experts have all made citizen science a powerful tool in gathering scientific data at scales that were earlier unimaginable. Take the example of iNaturalist yet again – think of a species, any species, and type in the name as a search keyword on the platform. What one gets is a world-wide map of that species, contributed by thousands of people from across the world, verified and validated by experts. A handful of scientists working in their specialist silos would take decades, if not more time, to match the scale and robustness of this data!

Most people find plants terrifying in their indistinguishable greenness, even though they are present everywhere, and everyone is taught from a very young age that we owe our existence to these magnificent beings. But millions of images of thousands of plant species contributed by enthusiasts everywhere have made robust learners out of the AIs of projects like Pl@ntNet, and made plant identification anywhere a breeze. Gone are the days of trawling through regional floras that were exclusive and unavailable for the masses, and aren’t we all glad about that!

Citizen science in India is newer still. Biodiversity citizen science projects are fairly easy to join and contribute to. India’s diverse ecoregions, habitats, flora and fauna make it a delight to document the natural world right from our backyards, especially birds.

There is a literal Great Backyard Bird Count that bird enthusiasts can participate in and that contributes to the global understanding of bird populations. The Asian Waterbird Census is touted as the very first citizen science project of India, conducted across wetlands with the aim of raising awareness on water birds. Both these are international events facilitated entirely, or in part, by the citizen science platform eBird and its India counterpart Bird Count India.

India Biodiversity Portal (IBP) and SeasonWatch are two completely homegrown citizen science projects. Their aim is to document biodiversity and changes in plant seasonal behaviour respectively.

IBP, much like iNaturalist, is a veritable compendium of biodiversity images. Some of its resources – like the plant species information pages – often act as accessible stand-ins for local floras with plant names, descriptions, distribution, and seasonality information all available in the same URL!

SeasonWatch tracks seasonal changes in trees across India, with the aim of understanding climate change. This is based on the assumption that as the temperature and rainfall patterns of the world change, so do the timing of leaf-out, flowering and fruiting of trees.

The data from this project are available as interactive elements on the project website. Here, contributors, or anyone with curiosity, can explore the effects of the environment on the seasonal behaviour of select trees. This type of information has the potential to act as early-warning for people whose livelihoods may be dependent on the seasonal production of flowers and fruits.

Citizen science data when curated, processed, analyzed and disseminated in the proper way, can find practical applications even for people who do not contribute information! One of the most effective uses of citizen science biodiversity data has been in the form of reports such as the State of India’s Birds (SoIB), which has immense application in species conservation, habitat protection, and policy development.

The SoIB is a neat, interactive compendium on the ranges and population dynamics of birds from across India over 20 or more years. These trends can help us identify birds that are most vulnerable to human-made changes.

MYNA (Mapping Your Neighbourhood Avifauna), based on eBird data, is another such interactive tool. It can help the beginner birder or the curious data explorer find out what birds they are likely to find in their locality. I personally love demonstrating this tool to undergraduate students, and enjoy seeing their faces light up with cheer when they see their neighbourhood birds!

These resources are available online and free of cost. They also have supporting documentation for use. All of this make these data ‘products’ invaluable education tools.

In 2020, the role of citizen science in building public knowledge was acknowledged by Government of India. Under the aegis of the Biodiversity Collaborative (a network of institutions and individuals committed to making biodiversity data accessible for application in conservation, sustainable development, and human well-being), the Cit Sci India Conference came into being.

This entirely online conference has been one of the most accessible platforms for citizen science practitioners to share and learn from peers not just during the conference, but beyond that through a Discord community. Hundreds of participants, from ages 10 to 70 years, have met annually for the past five years to exchange stories, learnings and data, while debating and discussing emerging concerns.

For instance, technology is evolving at a rapid rate, and contributing to citizen science may threaten contributor privacy. What steps can cit sci projects take to ensure contributor privacy is upheld? What are the best practices to verify, store and share cit sci data? How can practitioners ensure that data contributors get fair attribution for their efforts, and that data are used in only those ways that are beneficial to biodiversity and society? Who gets access to voluntarily collected data? Is it OK to make paywalled products based on these data?

These, and many other, concerns have formed the bases of lively discussions and creative solutions during the Cit Sci India conferences. If the enthusiastic banter on the community group is anything to go by, one can safely assume that citizen science as a concept is here to stay.

In conclusion, I would like to invite all the readers of this article to join a citizen science project and become part of a knowledge creation movement that is uniting humanity like no other! Like Joel, you could start small, with a biodiversity documentation app on your smartphone – and really see that ant or sparrow or peepal tree outside your window!

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!