Centering the people in children’s literature

This article discusses the need to foreground the lives and experiences of children from marginalized communities in children's literature. It argues that discussions surrounding children's literature have to go beyond literacy and engage with foundational questions related to equity, power and agency.

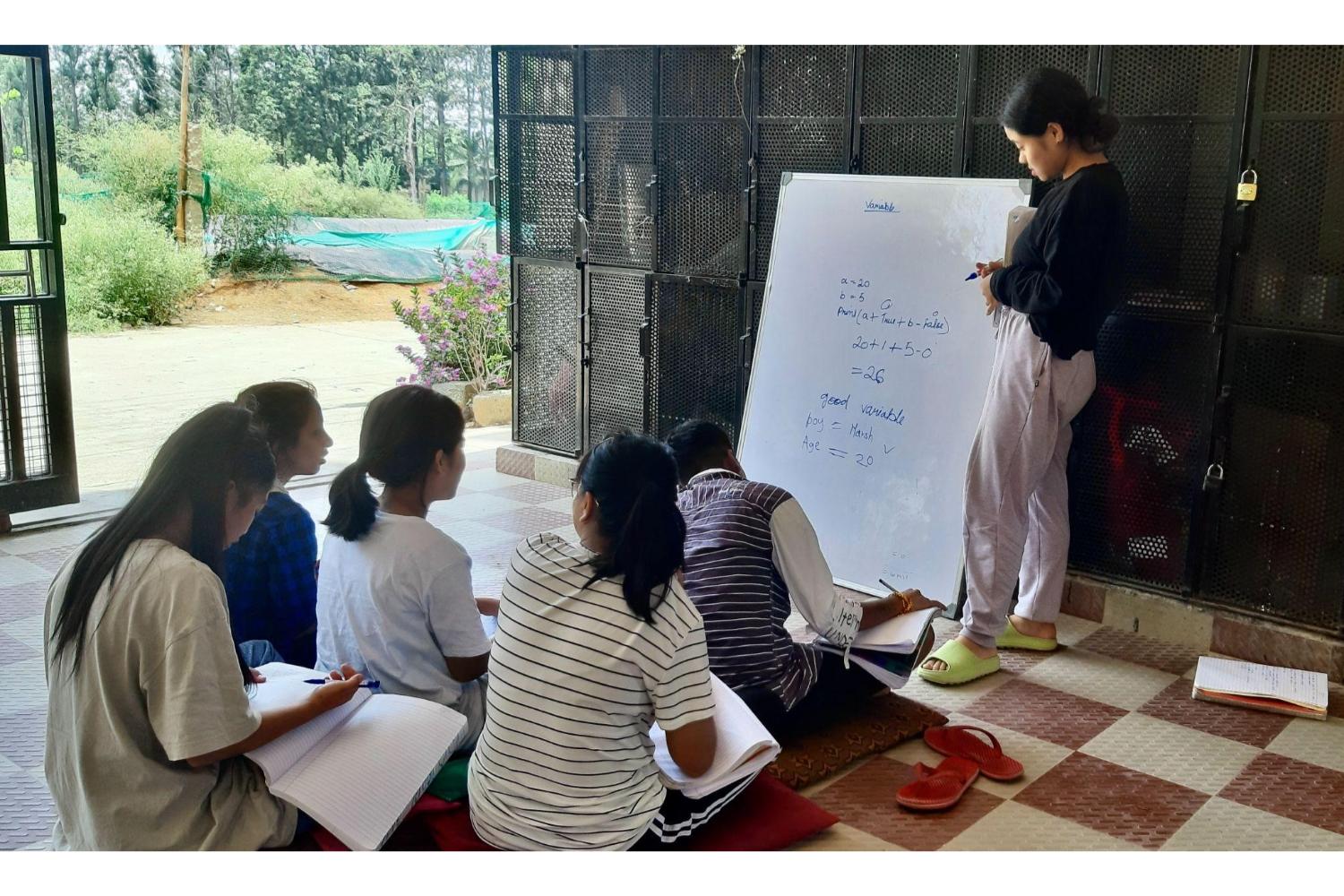

Photo credit: Narendra Pardhi

Works in children literature often marginalize the voices of children from historically marginalized communities. In this context, this article discusses the need of being conscious of our own and our children’s identities in relation to our work in literacy and literature. These aspects have defined our journey so far. It is hoped that such conversations would guide us more as publishers, teachers and librarians. These may also contribute toward enhancing the agency of those who have been deprived of the same.

Many of us are working with children from communities at the bottom of our country’s socio-economic order. They live in urban squatters, villages, tents on the roads and mountains where services do not reach. These Bahujan-Pasmanda-Adivasi-Dalit-Vimukta communities and children comprise 85% of our population groups. They have continuously been denied dignity and equal opportunities in the Brahmanical social order.

Examining ourselves

The mere fact that we are reading this article, in English, and that we have had access to education to be in the roles we are in, denotes a likelihood of our roots being in the Savarna castes within the Hindu varna order. Understanding that this social system is responsible for the deprivation which children live with, we need to be continuously thinking and working on ourselves as we are also products of this system and through our advantageous locations function as the inevitable decision-makers.

(Muskaan Publication, 2023)

Bree Picower1 writes about white people working on racial justice that figuring out (how to relate and function) is part of the work of being a white person involved in racial justice. This can get difficult as it requires us to move against what has become natural to our personalities–why am I saying something, when should I step back, when should I take space and more, going into a stance of doubt and questioning rather than arriving at easy answers with confidence. She reminds us, “this is nothing compared to what it means to navigate racism for black, indigenous and people of colour.” All of us are likely to reproduce this systemic injustice unless we question our own assumptions and ways of work.

Drawing from the contradictory reviews of a book, Mavli (2023), we can see how our own various positions, in this case, the religious identity can sometimes even color the atheists and progressive thinkers amongst us. In this book, Geeta Dhurve, the author brings alive the cultural practices of the tribal Gonds in respecting the fire and the utensils through the eyes of a child challenging her grandmother who believes that their ancestral spirits, in the form of Mavli, resides in them. The child in the story is questioning and exploring the existence of Mavli.

Ruby Hembrom, founder of Adivaani, writes that in the context of a religiously polarized state that, “the urgency of religious literacy arises, and the role of libraries in it is key. Libraries have the opportunity through religious literacy, to not only create the space for people to critically engage with their own and others’ religions, a reconciliation with prejudice and bias, and moments of reckoning, but afford dignity to those who practice it.”2

(Muskaan Publication, 2017)

Savarna Hindu reviewers commented that the book is ‘religious and establishes how faith is co-opting people into the community fold’. On the other hand, a tribal reviewer noted3 that the story “takes us closer to understanding the worldview and the strength hidden in the beliefs of the Adivasis, where the gods and deities don’t need grand monuments and tall structures to be remembered […] can exist in the smallest thing like the chulha or the pot upon it, and that’s why respecting and caring for each and every one is crucial. A child experiences the strength of the fire and thereby the deity.”

As the Gond children in our libraries read Mavli, they are excited and connect with the conversations in the book. It is heartening that while they get subsumed into the loudness of the organized religions around us, their own deities walk with them in parallel and hopefully when the fervor dies down, it is here that they will find their internal strength.

There are many such stories, and many children whose lives have been kept hidden, till now. These stories do not find publishers or the recognition they deserve because they are not in our comfort or sometimes, imagination zones.

As a person earning my livelihood in the education space, working with ‘Other people’s children’ (borrowed from Lisa Delpit), I need to, at the very least, strive that the opportunity of education is truly meaningful. I must also try to ensure that through my (misguided) ways, I do not end up furthering existing inequities. To address this, we must closely see and listen to the people and children we work with, learn from them, and be with them in real, authentic ways. We must also read and/or interact with people who have been able to theorize on these critical aspects of being an ally or a co-conspirator in challenging equations of power. Coming back to the school or a library space, we may be able to extend our boundaries through our direct engagement with books and children.

Photo credit: Muskaan

Literacy is just a point in the journey

In our country, particularly in the context of vulnerable social groups, the conversations are restricted to enrolments and foundational literacy skills. The clamor for literacy is seen in the ASER reports which continuously bring out results to show where children are lagging. The percentage of Std V children able to at least read a Std II text was 59.3% and for Std III children it was 23.4% in 2024. This is primarily about decoding. However, the child–the person– is absent in these numbers.

When we emphasize literacy in the space of education, we forget many things. We also ignore that the problem lies in the way the story of education has been woven. Literacy is not an end. It needs to be the space from where learners chalk their own lives and determine an end that is meaningful to them. It is not even the beginning point. When we begin to turn literacy completely on its head and bring the child into our focus, we are likely to solve the problem of inadequate indicators of literacy also. Drawing from Freire, the learner needs to make meaning of and interpret the world through the word. Sylvia Ashton Warner also spoke of this in her landmark book, ‘Teacher’ (1963).

Reimagining literature for children

As children’s literature grows beyond locally produced Amar Chitra Katha and British authors like Enid Blyton, Charles Dickens and Rudyard Kipling, it becomes more important to examine why these books have come to be read instead of the literature closer to our lives.

Written language emerged from and stayed a privilege of the elite classes. Therefore, the use of language to produce literature was a feature of the dominant communities and it largely presented their worldviews. Subaltern literature is a genre that emerged only in post-colonial years. In India, modern Dalit literature is noted to have evolved significantly post a conference on Dalit Sahitya organized in 1958 by Anna Bhau Sathe.

But what children should be reading is something which is still undergoing deliberations. This is largely because of the predominant view (in the Savarna adults’ mindset) that childhood (which is itself an imported concept) is a period of naivety and innocence. Our progressive ideas also keep sanitizing what the child ‘reads’. We prefer to be in the safe zone by being apolitical and by not engaging with the dark and unjust sides of society.

Photo credit: Muskaan

As a publisher, at Muskaan, we guide ourselves by the realities of children’s lives. ‘Barish ka ek din’ (Jackie Jaknore, 2007) and ‘Mitti’ (Madhu Dhurve, 2022) are stories of children living in vulnerable conditions in urban areas. Jackie presents an eventful day when he gets up with water gushing outside his house as the basti gets flooded. Madhu shows how her mother beats the odds to ensure her daughter gets some alone time to play with water at the public handpump. When these stories came to us, we knew they were working as a window for the privileged child to get a glimpse of a child who could be living in their city, while also providing a mirror to the children we all work with.

‘Gaanth’ (2024) takes the conversation to another level where we bring forth stories of three people witnessing the 1992 riots. One reads about the pain, hatred, doubts and violence in parallel to the friendships and family bonds being impacted by the turmoil, through the eyes of children. Trusting that if one child has lived it, another can read about it, we brought out this book.

Who will share these stories?

Every child has a unique story, their families, their communities, different situations and their own responses to the same. There are many commonalities also, which connect us across geographies, but they still remain unique. It is evident for the authenticity of the story that it is best told by the person who has experienced it.

This takes us to the question of feasibility and seriousness in the work of children’s stories written by children and young adults of vulnerable communities. As adults, we must remember that children are not just consumers of knowledge but also creators of knowledge.4 Dyson (2016)5 points out that children are constantly writing and composing in conversations, movements, friendships and relationships. This is extended to texts when literacy is introduced in an authentic manner.

When we recognize that children are composers themselves, we are acknowledging their agency. Mathis (2016)6 writes “Agency is considered here as making one’s identity and perceptions visible and actively acknowledged by others to enhance and empower the personal, cultural, and social aspects of one’s life.” In terms of writing, Janks (2010, p. 156)7 argues that “the ability to produce texts is a form of agency that enables us to choose what meanings to make,” which she sees as akin to Freire’s (1972) understanding of ‘naming the world’.

Encouraging our children and young readers to write offers insights into children’s personal experiences, identities, and imagination. When children write, they are not asking for pity rather they ask to be seen. This is, in itself, an act of exerting one’s agency, refusing erasure. It takes a lot of power simply to persist, for lives lived at the edges.

M. Pandey, aged 11 years, in the book ‘Rakhi ke laddu’ (2022), writes “I was hungry but there was nothing at home and my mother had gone to cook in other people’s houses. I took out the two laddus from the box we had kept hidden from ourselves so that we could have had these for Rakhi. But I would not call this stealing.”

Photo credit: Muskaan

This book, co-published by Muskaan and Eklavya, came out of a writing exercise by children. In the quote shared above, it is evident that the author is feeling safe to share her vulnerability, of hunger, of having a working-class mother, of poverty and moreover of doing something an elder had told her not to do.

In Muskaan, we have published many stories written by children and young adults who are writing from their own lives. But at times, we were weaving our observations in and converting them into story books and/or editing some stories written by the children. It took us time to be aware of what we were doing and recognize the need to step back and/or play the role of an editor and a facilitator rather than the main actor.

Cazden (2001)8 points out that the individual scaffolding strategy involves dyadic interactions in which an adult and a child engage in power sharing. This event is usually marked by adults’ attempts to extend children’s zone of competence, which Vygotsky (1978) deems the ‘zone of proximal development’. In an effort to strengthen the stories, as an adult, we now introduce new resources, challenges and information which extend the thinking of the author to produce beautiful results. This could be done on a one-to-one basis or as a collective group exercise where peers can also give feedback and collaborate.

‘Going to school alone’ (Simran Uikey, 2019) was a self-written experience of an Adivasi child who was fearful of going to school without her familiar circle of friends. To enhance the political sharpness of the story, elements of subject-content were introduced in relation to the author’s own world of experiences. ‘Ek shahar, ek pahad, ek mohalla’ (Eklavya, 2023) is an exceptional testimonial piece of writing by adolescents living near a landfill site exploring their space.

Space for changing the balance in classrooms

While not enough in numbers, these are storybooks that offer opportunities to discuss inequalities and injustices. Many experiments have shown that children can bring in nuanced interpretations of various situations. They are also able to present their arguments and thoughts, when in a space they are heard and feel heard.

As they read ‘Pongal’ (2020) and ‘Mirchi ka chura’ (2021), the young readers at Muskaan relish Bama’s protagonists challenging the caste order. There are times when, as a teacher from a privileged background, some of us are uncomfortable when we discuss social stratification. “How come they have such big houses. Where did they get them from?” “Didi, the colony guards don’t open the gates for us to reach your house.” We talk about children earning their money to buy warm clothes in ‘The new sweater’ (2015) and I am conscious of having several sweaters in my cupboard. But as written earlier, we have to ‘figure out’ our discomforts but the conversations need to continue. Using stories like ‘School mein seekha aur sikhaya’ (2022) can be discomforting for teachers as students would share what they find problematic in schools, as was observed in Jyoti’s class.9

Artwork: Karen Haydock

Using a set of texts with elements of conventional notions of theft and law and order, Ragini and Shashi also share rich classroom discussions10 that point to the nuances that young readers’ understandings of criminality, justice and power hold. Instead of simplistic definitions of right and wrong, good and evil, or certain ‘correct’ interpretations of what is ideal behavior, these readers view the actions of protagonists—and in turn their own—as informed by the structures acting upon them and how they choose to push and pull as agents within those structures.

These are all rich discussions that touch the core of education—of critical literacy. The theoretical grounding of such work is being borrowed from Freirean11 ideas of “reflection and action upon the world, in order to change it.”

Conclusion

Children are not born with the compartments of religion, gender, caste or class that we adults are more fixed in. By promoting children’s agency to build on what they know and to take control while making sense of new symbolic tools (of literacy) for participating in the world, they have the potential to transform their worlds and their very selves.

In this journey of transformation, the adults need to be able to free themselves from ego and the burden of being right. Stretching our boundaries, faltering yet bringing our attention to lives that are increasingly silenced—through conversations, reading, writing and publishing—into the centre of our work is the way forward.

References

Bama. Mirchi ka chura. Illustrated by Karen Haydock. Bhopal: Eklavya. 2021.

Bama. Pongal. Translated by Amita Shirin. Illustrated by Karen Haydock. Bhopal: Muskaan, 2020.

Dhurve, Geeta. Mavli. Illustrated by Heera Dhuvre. Bhopal: Muskaan, 2023.

Dhurvey, Madhu. Mitti. Illustrated by Ubitha Leela Unni. Bhopal: Muskaan. 2022.

Dhurve, Nikita. School mein seekha aur sikhaya. Illustrated by Shefalee Jain. Bhopal: Muskaan. 2020.

Dhurve, Paptu. Naya sweater – the new sweater. Illustrated by Soumya Menon. Bhopal: Eklavya, 2015.

Jaknore, Jackie. Barish ka ek din. Illustrated by Kanak Shashi. Bhopal: Muskaan. 2007.

Mourya, Maya, Rubina Khan, Lata Sangade, et al. Gaanth. Illustrated by Shayoni Das. Bhopal: Muskaan. 2024.

Pandey, Muskan. Rakhi ke laddu – laddu for Rakhi. Illustrated by Sagar Kolwankar. Bhopal: Eklavya. 2020.

Samuh, Ankur Lekhak. Ek sahar, ek pahad, ek mohalla. Illustrated by Allen Shaw. Bhopal: Eklavya. 2023.

Uikey, Simran. Going to school alone. Illustrated by Kruttika Susarla. Bhopal: Muskaan. 2019.

Endnotes

- Picower, Rice. Reading, writing, and racism: disrupting whiteness in teacher education and in a classroom. Boston: Beacon Press, 2021.

- Hembrom, Ruby. Religious identities in the library. Bookworm beyond borders, no. 9 (2023).

- Kerketta, Jacinta. Mavli. The Book Review 48, no. 11 (November 2024).

- Lisanza, Esther Mukewa. Rafiki: a teacher-pupil. In Child cultures, schooling and literacy, edited by Anne Haas Dyson, 201–215. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Dyson, Anne Haas. Child cultures, schooling and literacy. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Mathis, Janelle B. Literature and the young child: engagement, enactment, and agency from a sociocultural perspective. Journal of research in childhood education 30, no. 4 (2016): 511–527.

- Janks, Hilary. Literacy and power. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Cazden, Courtney B. Classroom discourse: the language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2001.

- Taneja, S., and Jyoti Deshmukh. Children’s voices in school stories. Learning curve 15 (2022): 23–26. ISSN 2582-1644.

- Lalit, Ragini, and Shashikala Narnaware. Experiences of classroom talk around criminalization, individual agency and morality with young readers from marginalized communities. Paper presented at the Children and YA literature conference, Jadavpur University, August 2022.

- Freire, Paolo. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Translated by M. Bergman Ramos. New York: Continuum, 1970. Reprinted in Penguin Classics, 2017.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!