Embracing multilingualism – A journey of love, language and learning

For over 16 years, Amma Social Welfare Association (ASWA) has been working with underprivileged children and communities. We have been intervening in education, well-being programs, and social empowerment initiatives. As a co-founder of ASWA and project leader of the School Education Wing, I have worked closely with children from diverse linguistic, social and cultural backgrounds. […]

For over 16 years, Amma Social Welfare Association (ASWA) has been working with underprivileged children and communities. We have been intervening in education, well-being programs, and social empowerment initiatives.

As a co-founder of ASWA and project leader of the School Education Wing, I have worked closely with children from diverse linguistic, social and cultural backgrounds. Through these we have tried to create spaces where they feel seen, heard and supported.

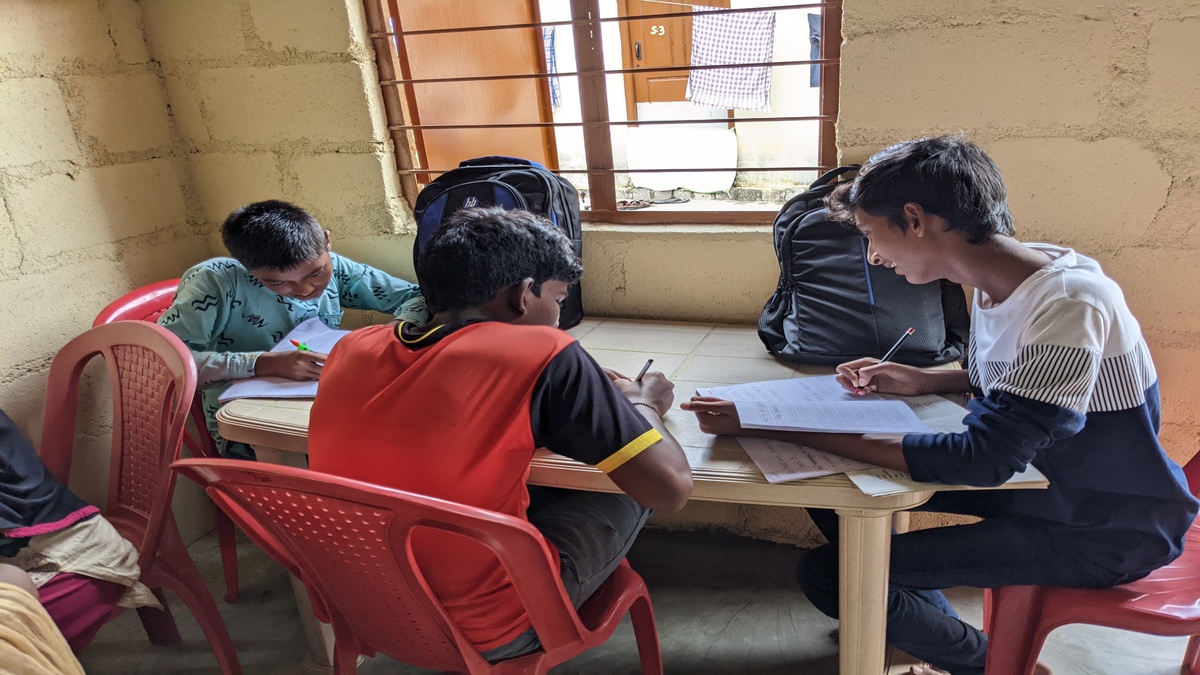

ASWA’s full-time Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) and library interventions operate in Shadnagar and Ameerpet in Telangana. We support four government primary schools and run two Children’s Learning Centers as a part of this process.

Our mission is simple. It is to nurture children’s FLN and language competencies and emotional growth. We do this by fostering an inclusive learning environment. We honor the children’s unique backgrounds. These children study in under-resourced governmental primary schools. Often they belong to underprivileged communities.

A significant part of this journey involves navigating the complexities of multilingualism. This is especially so, since 80% of our students come from non-Telugu-speaking families.

But the heart of our work lies in the stories of the children themselves. This involves seeing their resilience, curiosity, and capacity to learn in the face of language barriers as resources. In this article, I share some stories highlighting how embracing a child’s native language can unlock their potential and create a love for learning.

The challenge of multilingualism: a path to connection

Before I became a full-time teacher in 2018, I had volunteered with ASWA for over a decade. I was then conducting weekly sessions at Government Primary School, Bulkumpet, Hyderabad. My work relied on love and play to engage children. However, my full-time experience opened my eyes to the deeper complexities of children’s learning, particularly those realted to multilingualism.

In the government primary schools we work with, children come from diverse backgrounds. Often, they come from states such as Bihar, Assam, Odisha and Karnataka. Sometimes they also come from marginal communities such as the Lambadis.

These children were often discouraged from using their native languages in class. This was leading to a sense of disconnection and disengagement from learning. Many students struggled to grasp Telugu, the medium of instruction.

However, when we incorporated their native dialects into the classroom, the results were immediate. The children felt seen and heard, and their learning improved.

I started encouraging children to use their home language freely in class. At first, I didn’t know any language other than Telugu. I was unsure since I didn’t understand their home languages. However, with the children’s help, we created an environment where everyone felt safe to speak.

The change was immediately noticeable. The children’s confidence grew. They became eager to learn. This lesson wasn’t limited to other language-speaking children. Even among Telugu-speaking students, dialect differences created obstacles. The key was embracing each child’s unique linguistic background as a strength rather than as a barrier.

Success stories: Bujjamma and Narasimha

Two children, Bujjamma and her brother Narasimha, had long been labelled by the teachers as ‘unfit for learning’. This was simply because they struggled to grasp concepts in a language they didn’t fully understand.

We started working with them in a way that valued their native tongue and personal experiences. Then they began to thrive. Earlier Narasimha was shy and withdrawn. When we started addressing his context, he excitedly began learning his name and numbers. Bujjamma, too, came out of her shell. She started sharing stories. She also began participating in class activities.

These children weren’t unfit to learn. They needed an environment honouring their identities.

Understanding context: a key to unlocking potential

In every classroom, I heard stories that ranged from happy to sad. I remember Swathi, a young girl, telling me about her family’s trip to the Medaram Jatara for selling rings. She shared, “Teacher, we had nowhere to sleep. And my mother rested by the chicken market, where it smelled terrible. We didn’t have anything to eat.” Another child, Arathi, said, “I didn’t eat today because I couldn’t go begging.”

These are not just stories. These show the children’s daily struggles. By understanding their lives, we can teach in a way that educates and supports them emotionally.

Over time, I realized that to teach a child truly, we must first understand their lives. What do they experience every day? Who do they turn to for help? By stepping into their world without judging them, we can help them reach their full potential.

We began to understand that we needed to follow certain methods to connect their context to learning. During this time, we came to know about Maxine Berntsen’s balanced approach. This method is beneficial for connecting children’s day-to-day experiences to their learning.

Beyond words: understanding emotional contexts

Teaching language isn’t just about vocabulary. It’s about understanding the emotional context behind the words. For many children, words like ‘amma’ (mother) or ‘nanna’ (father) carry emotional weight due to family circumstances.

Two students, Hari and Siva, don’t have their fathers living with them. These men have left their mothers. Because of this, they don’t like learning their father’s name. Instead of ‘nanna,’ they prefer to learn words like ‘mama’ (uncle) or ‘tata’ (grandfather).

Teachers can only recognize this when they understand the children’s backgrounds. So, we move on and teach them the words they feel comfortable with.

Rohit and Mohit, two brothers from Bihar, also left a lasting impression. After their biological mother passed away, they lived with their stepmother.

She treated Mohit poorly. She beat him and didn’t feed him well. However, she maintained a good relationship with Rohit. Mohit always wants to learn his biological mother’s name. Whereas Rohit learns his stepmother’s name.

We acknowledged their emotional struggles. We also gave them the space to express themselves. By doing so, we helped them to learn based on their interests and connections. Empathy and patience are crucial to helping them engage with learning meaningfully.

In our classrooms, we emphasize the importance of empathy and inclusion. One day, a child named Akhil shared that he had eaten cat curry for breakfast. When the other children laughed, I turned the moment into a lesson on respecting cultural differences. These real-life experiences allow us to teach literacy and values like empathy and respect.

Critical thinking and addressing societal norms

At our Children’s Learning Centres (CLCs), we often encounter questions from the children like, “Why don’t girls continue their studies?” or “Why do parents enrol boys in private schools but see girls as burdens?”

These difficult and emotional questions come from their lived experiences. Our role as educators is to give them the space to ask, reflect and learn.

Multilingual classrooms also allow children from different cultures to ask questions and challenge societal norms. A young Muslim girl once asked, “Teacher, why do we pray to God if humans create everything? Why are you putting bindi, and why are we not putting anything on our faces? What would happen if we didn’t follow the rules created by elders?” These are not just questions. They reflect deep-rooted societal challenges children face daily. When she asked these kinds of questions, I was shocked. I too started asking myself questions. “Why am I following these things?”

Acknowledging their questions and emotions, we help them grow academically, emotionally and socially. These moments are opportunities to foster critical thinking. These can be used to encourage children to explore the world around them with curiosity and courage.

Our library sessions also play a crucial role in this process. These help children to know and understand different contexts and cultures etc. We connect with the children’s realities through stories and help them navigate their feelings.

One day, while reading aloud the book Jamlo Walks, children reflected on their own COVID-19 experiences. They shared how they went to different homes for food and were often ignored.

Parents’ role

Parental involvement is another critical factor. This is particularly so in multilingual settings at CLC. Sandeep, a third grader whose mother spoke Marathi and father spoke another language, struggled with Telugu. Sandeep has made remarkable progress in the language by working closely with his family. He encourages them to speak Telugu at home. He also asks them to put on Telugu channels while he watches TV.

We also organize parents’ meetings and sessions on parenting and educating girls. In one case, a 15-year-old girl Nandini’s marriage was fixed when she was only three years old. However, her parents are in a dilemma to continue her education or to go in for marriage.

Influenced by our sessions, the community has been taking the responsibility for stopping child marriages, even being willing to inform the police. Our consistent efforts have brought about a clear shift in parents’ mindsets. One community leader, Dasarad, praised our work, stating, “If such organizations existed in our time, we wouldn’t have stopped our children’s education.”

We also observe that many boys’ behaviour is influenced by their fathers. These men often drink and use abusive language. They also engage in domestic violence. To address this, we have held meetings with the fathers. In these we share the real-life situations their children face.

We emphasize that children observe and imitate their parents’ behaviour. We gently encourage the fathers to be more mindful of their actions. The response has been positive. Many fathers have begun adopting healthier communication and behaviour patterns at home.

Challenges

As a teacher, I have faced challenges like language barriers when working with multilingual children. Understanding their multicultural backgrounds and managing diverse learning needs has taken time and effort.

Around 10% of the children in our classrooms are still hesitant to open up. Many of them often migrate or take long leaves for family reasons.

Unfortunately, many schools also don’t prioritize getting to know the children on a deeper level. This has also been a challenge.

Moving forward

These challenges have become learning opportunities for me. My success in sparking eagerness to learn comes from providing safe spaces where children can freely express themselves and connect lessons to their daily lives. I focus on understanding their emotional states and addressing the root causes of uncertain behaviours.

I enjoy interacting with children from different backgrounds. I feel deeply satisfied with every improvement I see in them.

The changes may seem small. However, they are influential in helping children connect to learning. Ultimately this has the potential to help them grow into kind and thoughtful individuals.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!