Learnings from the library: children’s affective responses to literature

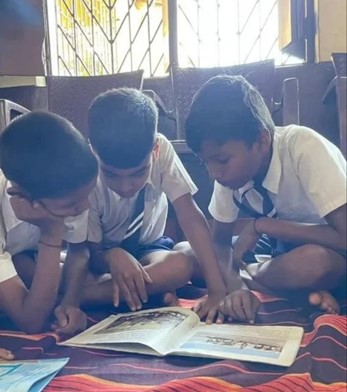

Library experiences with children have repeatedly demonstrated that children are capable of high emotional literacy when presented with texts that trust the mind of the child as well as honor the complexity of lived realities. These emotional competencies are strengthened through sustained engagement with stories in a shared space. This article explores children’s affective responses to literature in the context of library work.

“Don’t be childish.”

”अजूनही मन लहानच आहे तुझं” ।

“Bachpana mat karo.”

“Pillerkali!”

These are not uncommon phrases for adults across languages and communities, demonstrating that we have long known that emotional and cognitive competencies are developmental. However, in more modern times, we have begun to label these competencies, more clearly, as emotional literacy (Steiner, Claude. 1979) and/or Social Emotional Learning (SEL). We know from research that children’s emotional literacy predicts academic, mental health and positive social outcomes (Burchinal et al., 2020).

Human beings, ever since the fire pit, have understood that these competencies awaken, strengthen and are negotiated through stories and in shared spaces, even if they did not articulate it as such. The continuation of cultural transmission through stories in resilient communities is evidence enough. With modernity, there has been a seismic shift into a multi-modal world consisting of images, signs, symbols, sounds, etc.

The library as a space for understanding more about children’s emotional responses through literature is a logical outcome. The power of literature to enable us to evoke our emotional selves may explain why practitioners both within the library as well as in the areas of mental health are increasingly using books, particularly picture books, to strengthen emotional resilience. We see this reflected in the children’s publishing industry as well, and it brings hope.

Reader Response Theory (Rosenblatt, 1995) in action is one of the thumping veins of Bookworm’s pedagogical practice. Listening to children in praxis is what we are continuously aspiring toward. This is because childhood, and our understanding of its complexity, diversity and varieties, are still seriously under-researched areas in India. In the library, we learn as we listen, we learn as we read, and we trust that the children are doing so as well. For this article, we focus on two aspects of ‘affective’ responses to literature, which we argue have developmental implications and relevance for social, cultural, linguistic and cognitive learning as well.

Our framing of the responses is presently from close observations and recording of children’s oral responses in our various library sites. In the library, we recognize emotional vocabulary to be a powerful entry point into emotional literacy. We know from language development that naming enables the human mind to identify, think about, categorize, express and comprehend. In this case, an emotional vocabulary elicited through a story experience proves to be powerful for many children.

We recall the word ‘lost’ in the title of ‘Payal is lost’ (Muskaan, 2019) as one that elicits from various children, emotionally traumatic and heroic stories of being lost in ‘zatras’/fairs, or of being found, of finding and deduction. In the mere recounting of memory connections with a word like ‘lost’, children are enabled to think of themselves as now competent, resilient beings. This also enables them to think back, reflect, and articulate emotionally charged experiences for themselves and others.

These seemingly everyday acts of language are ways in which the narrator shapes their own story of self. As library educators, we are constantly provided with these opportunities to give “full credence to the seriousness of the child’s predicaments, while simultaneously promoting confidence” (Bettelheim, 1976). This is because we know that in making meaning of situations like these, children are growing in self-confidence. Emotional connections of this kind abound in library practices that include daily read alouds across more than 20 sites.

In almost every group, an emotionally charged event elicits a connection that allows the child to answer the fundamental questions that literature seeks to answer, “What is the world really like? How am I to live in it? How can I truly be myself?” (Bettelheim, 1976). ‘Mother is mother’ (CBT, 1968), ‘Angry Akku’ (Pratham Books, 2017), ‘Boo, when my sister died’ (Pickle yolk, 2017), ‘Breaking moulds’ (Art1st, 2023), and ‘Tsunami’ (Tara Books, 2009), are a few of the many books that we have recorded as ‘emotionally charged’ texts. These books compel evocations amongst a variety of children readers.

Emotionally charged plots enable children to activate their prior knowledge schema to connect and draw connections with the story emotionally from direct or lived experience. In this way, they amplify their meaning-making about themselves as well as that of the text. We note that children (often based on age) demonstrate two types of emotion vocabulary. One is a vocabulary that is emotion-specific like happy, angry, sad or lonely, which almost immediately allows them to understand the character and themselves better. As they grow older and are exposed to more complex life experiences and literature, they are able to enter into conversations around other emotional states like fear, wonder, jealousy, prejudice, justice, affection, attraction, love and injustice, etc.

We are often humbled by the responses children articulate in stories that lend themselves to more complex dilemmas of human emotion and cognition. We recognize that responses to literature that are emotionally charged also allow children to think and imagine counterworlds (Zipes, 2012). The distance between the story’s events, their own lives, their understanding and the space of the library interaction, allows children (and adults) to step back, consider the dubious morality of life, and think about steps to reform it and us.

In ‘Jamlo walks’ (Penguin, 2021), some readers have rejected the ambiguous ending. They have consistently declared that Jamlo does reach home and is reunited with her parents. There is a denial of the inevitable and an agency to correct this wrong in their articulation that is always heightened by emotions and is coherent. In ‘The story of a panther’ (Orient Longman, 1998), killing the panther evokes huge moral outrage despite locating the text in time and place. The readers speak on behalf of animals, demonstrating that they can take positions outside of themselves to serve justice and talk about how power can corrupt us as human beings.

This has been echoed in reading ‘Uncle Nehru, please send an elephant!’ (Tulika, 2021), when a reader quietly asked, if anyone had considered thinking about the elephants and what they would like, when shipping them to distant countries. In ‘Pongal’ (Muskaan, 2021), children raised on a diet of merit and hard work are unable to grapple with the unfairness Madasami and family undergo in giving their best produce to the landowner. Over various retellings in library sites, they repeatedly agree with Esakkimuthu’s claim, “If we are paying him a visit during Pongal, isn’t it right that he should also pay us a visit with his family during Deepavali or New Year? Does he ever do that?”

In ‘I will save my land’ (Tulika, 2017), having the grandmother reprimand Mati’s father for his gendered views on land ownership has evoked glee and a strong sense of ‘righteousness’ that even young male listeners agree with in principle. In ‘Guthli has wings’ (Tulika, 2019), children are often confident that the parent who will give in, who will get Guthli’s desire to wear a dress, is the mother. They are not always confident of the community. However, they have deep faith in the stewardship of the mother. Children immediately know that the mother will understand and that she will enable Guthli’s choices demonstrating mature emotional and social intuition.

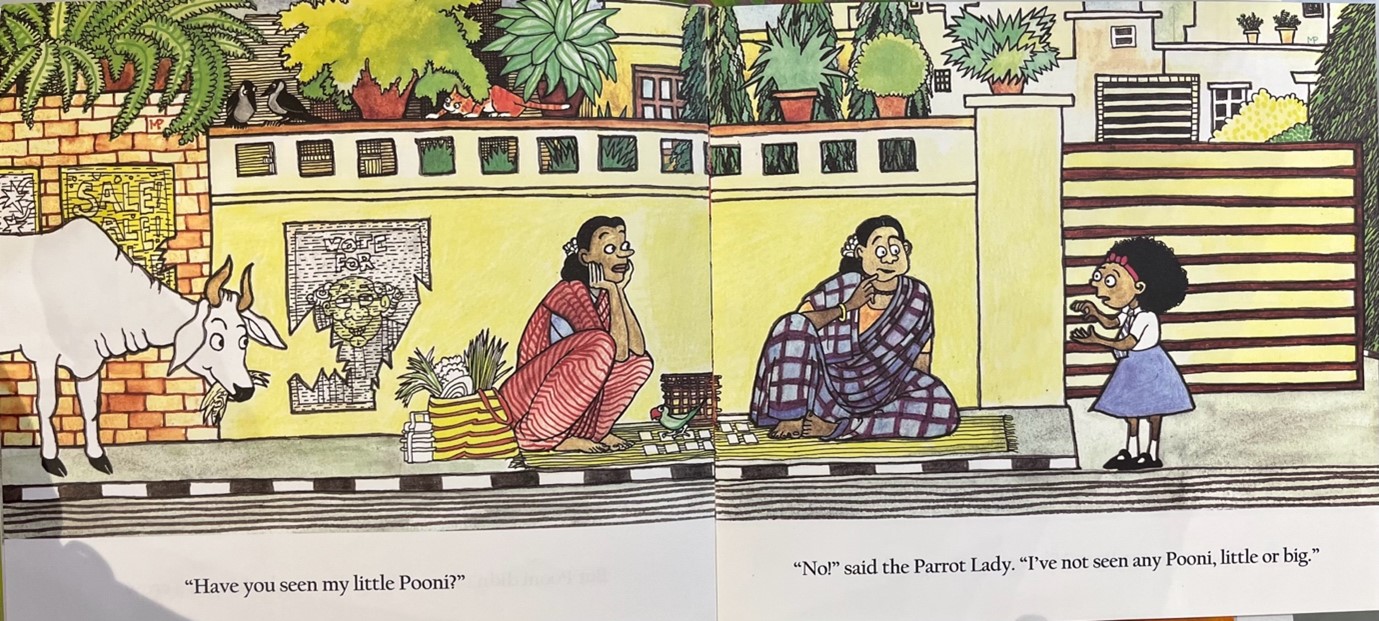

In responding to the book ‘Beauty is missing’ (Pratham Books, 2022), children in one community were quite sure that if they needed help with finding someone or some animal who is missing, they wouldn’t approach the police first. They would rather seek help from neighbors and friends. The police for many children are a ‘feared’ entity. They bring that reflection into their affective responses and begin to engage with realities of power and negotiation.

What children repeatedly demonstrate is that they are capable of high emotional literacy when presented with texts that trust the mind of the child and honor the complexity of lived realities. In conversations that explode with ‘emotionally charged’ texts, children are navigating psychosocial realities, testing their own abilities to articulate points of view and clarifying, for themselves, good reposes for a better world.

We are confident that children who are raised on a diet of ‘sanitized’ texts, linear plots with safe endings and narratives that continue to reproduce the status quo in a stratified society are unable to be empowered in quite the same way. Often flat, safe stories that are imagined by well-meaning adults to be good for children disempower and do not allow the child the opportunity to think about, connect and find resonance with lived reality.

We have long held that children deserve more complex stories. Good writers show us how they present these with lightness and with humor, surprise and joy. ‘Putul and the dolphins’ (Tulika, 2006), ‘I am a cat’ (Eklavya, 2010), ‘Snip’ (Pratham Books, 2017), and ‘My chappals’ (Muskaan, 2019) are some of the seemingly simple stories that ignite and delight with emotional responses.

Readers, as young as seven or eight years old, listen to the unfolding drama and humor of infatuation in ‘Watermelon route’ (Jyotsna Prakashan, 2008), while older readers quickly connect with classroom crushes. The more aware teens have shared how complications may arise if the boy actually pursues the girl without family support. All ages enjoy the story but bring varied affective responses to the text. Children are capable of much more than we often imagine. The space of the story through literature are powerful underground passages toward resilience and empowerment. The library enables this passage.

References

Bettelheim, Bruno. The uses of enchantment: the meaning and importance of fairy tales. New York: Random House, 1976.

Burchinal, Margaret, Timothy J. Foster, Kristen G. Bezdek, Megan Bratsch-Hines, Clancy Blair, Lynne Vernon-Feagans, and Family Life Project Investigators. “School-entry skills predicting school-age academic and social-emotional trajectories.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 51 (2020): 67–80. Rosenblatt, Louise M. Literature as Exploration. New York: MLA, 1995.

Steiner, Claude. Emotional literacy: intelligence with a heart. Bloomsbury, 1979.

Zipes, Jack. The irresistible fairy tale: the cultural and social history of a genre. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Children’s literature

Cariapa, Devika. Uncle Nehru, please send an elephant! Illustrated by Satwik Gade. Chennai: Tulika, 2021.

Dhurve, Janna. My chappals. Illustrated by Tasneem Amiruddin. Bhopal: Muskaan, 2019.

Greban, Quentin. Watermelon route. Jyotsana Publication, 2008.

Jha, Richa. Boo, when my sister died. Illustrated by Gautam Benegal. Noida: Pickle Yolk Books, 2017.

Jimo, Canato. Snip. Pratham Books, 2017.

Joydeb, and Moyna Chitrakar. Tsunami. Tara Books, 2009.

Karim-Ahlawat, Mariam. Putul and the Dolphins. Illustrated by Proiti Roy. Chennai: Tulika, 2006.

Kuriyan, Priya. Beauty is missing. Tara Books, 2022.

Mirza, Maheen, and Shivani Taneja. Payal is lost. Illustrated by Kanak Shashi. Bhopal: Muskaan, 2019.

Mishra, Samina. Jamlo walks. Illustrated by Tarique Aziz. Gurugram: Penguin, 2021.

Rinchin. I will save my land. Illustrated by Sagar Kolwankar. Chennai: Tulika, 2017.

Rinchin. I am a cat. Illustrated by Jitendra Thakur. Bhopal: Eklavya, 2010.

Shashi, Kanak. Guthli has wings. Chennai: Tulika, 2019.

Shankar, and Pulak Biswas. Mother is mother. Delhi: CBT, 1968.

Bama. Pongal. Translated by Amita Shireen. Illustrated by Karen Haydock. Bhopal: Muskaan, 2021.

Shroff, Vaishali. Breaking moulds. Illustrated by Shivam Choudhary. Delhi: Art1st, 2023.

Varma, Vinayak. Angry akku. Pratham Books, 2017.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!