Land-relations, caste-system, gender and social justice are topics that don’t come immediately to mind when talking about children’s books. However, these are issues that are inescapable for millions of children across the country. Their everyday lives are stories of struggles, and in some cases, of triumph over these struggles.

These narratives can fill several volumes of books. Despite this, these are not issues that are generally considered apt for children. Therefore, they do not find their way into children’s literature too often. These also do not get discussed enough in spaces of learning.

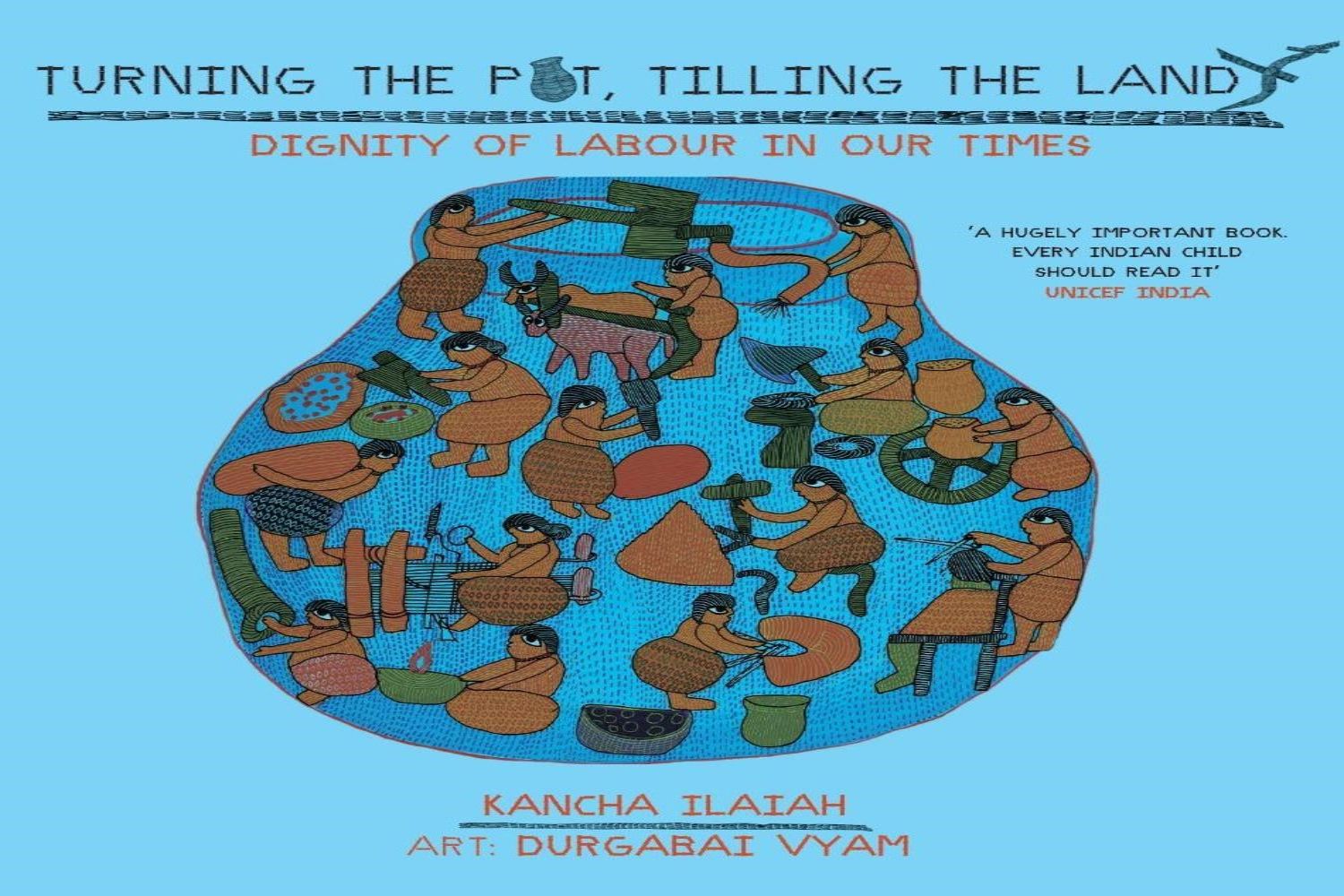

The beautifully illustrated book Turning the Pot, Tilling the Land, focuses on these very fraught topics. It has been written by Kancha Ilaiah, a prominent Indian scholar, writer and anti-caste activist. It has been published by Navayana, and illustrated by Durgabai Vyam, an artist belonging to the Gond tribe.

In the book’s introduction, Ilaiah alludes to the 2006 protests by medical students against caste-based reservation for seats in central educational institutes. Some forms of these protests (that struck the author) included students taking to the streets and sweeping roads, polishing shoes, etc. They did this as a mark of the ‘lowly’ nature of these jobs and what the students would have to turn to if denied seats.

Ilaiah calls out how deeply embedded the notions of caste, and the lack of dignity of labor associated with the so-called lower castes, are within our society. Turning the Pot, Tilling the Land tries to introduce frameworks that enable children to appreciate the dignity of labor, the embodied knowledge that one acquires while performing productive labour, and its development through history. The book also illustrates how these processes intersect with social structures of gender and caste in India.

Each of the book’s chapters deals with different communities and occupations. Throughout its eleven chapters, Ilaiah highlights how the caste system in India has relegated communities engaged in life sustaining tasks such as the tilling of land, leatherworks, pottery, farming, etc., as ‘lower’ castes. In contrast, those born into the so called ‘upper castes,’ and revered, are often those engaged in non-productive occupations.

For example, chapter 7 of the book focuses on the irony of the caste group of the dhobis (cloth washing community). These communities, who discovered soap, cleaned clothes, and helped maintain hygiene, have been branded as an ‘unclean’ caste under the backward/other backward caste groups across different states in the country.

This thought-provoking book provides a critical analysis of the social, political and economic conditions of different ‘labor caste groups’ and the ‘non-productive’ upper-caste groups, as Ilaiah refers to them. He argues that currently Indian society is structured in such a way that the caste system is deeply embedded in every aspect of life. It structures everything from education to economics, politics to religion.

Ilaiah discusses how the denial of education to the laboring castes, has limited scientific advances in this country. He also emphasizes the importance of challenging the caste system and promoting a more equitable food and labor system that values the contributions of all individuals regardless of their caste or social identity.

For children who remain unexposed to these issues, this book provides ample opportunities to delve into these ideas. It can also help them understand linkages between the ideas across different chapters. It is simply written. Different sections within chapters carry small nuggets of facts and questions, which can be explored further.

However, the ideas being dealt with are not simple or straightforward. These would need appropriate guidance and support from educators, parents and facilitators. This would help younger children navigate and critically engage with the book’s ideas.

For example, the chapter on farmers includes two sections that can be explored further by children. One of these revolves around understanding seasonality and cultivation. It has multiple questions that can enable the facilitator to introduce different concepts. These include seasonality and climate change, political economy of farming covering either one or multiple themes, such as caste and land ownership, focus on cash crops, need for multi-cropping etc.

However, the facilitator would need to set enough context before delving into critical discussions. They will also need to provide access to other resources, such as, additional books, videos, articles and experiential processes, for children to meaningfully engage in these discussions.

Another way to explore the intersectionality of caste, labor, gender, etc. is through the beautiful illustrations that accompany each chapter. For example, in the chapter on potters, some of the illustrations showcase men and women engaged in different activities in the process of making pottery. The facilitator can perhaps decide to focus on the concept of gender roles for further study through this chapter.

Another possibility for further exploration for students could be the artform itself. One could understand more about the Gond tribes, their spread across the country, the development and evolution of the Gondi artform, the focus on nature in most paintings/illustrations, the uniqueness of the use of dashes and dots in the illustrations, etc.

Introducing these ideas to children with appropriate guidance and sensitivity, providing spaces for experiencing and engaging in relevant work, whether it be cleaning, gardening, working with clay, etc., and critically discussing and questioning the connections between food, labor, caste and gender, would perhaps provide a better understanding of how systems of oppression pervade all aspects of life in the country. It can also help our children develop an understanding about how promoting social justice requires a comprehensive approach that addresses these interwoven systems of inequality.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!