An inclusive and effective higher education

In her article titled ‘An Inclusive and Effective Higher Education,’ discusses the learnings from a field intervention that addresses the learning needs of underserved communities through a flexible, self-paced, peer-driven model that also makes the learners job-ready.

A pedagogical approach to simultaneously solving for inclusion and effectiveness

Rani grew up in rural, tribal Maharashtra. Imagine Rani at her place of work. What did you imagine her doing? Could you imagine her working on a laptop, typing away lines of code, creating marketing collaterals, and contributing to the knowledge economy? Is she able to participate in high-aspiration jobs and careers that can help level the social and financial inequities of the world where she was born?

Usually, the answer to these questions is a no, because the pathways to this life are inaccessible to people coming from marginalized communities, especially women. Can we design an inclusive and effective higher education system which changes that?

To answer this, let us first answer what the purpose of higher education is. When can we say that an individual has received an effective higher education?

- Is it when their education enables learners to gain skills that empower them to be gainfully employed/self-employed?

- Or is it an effective education only when it imparts skills and mindsets that enable people to continue to learn on their own, to keep themselves relevant in an ever evolving world of work?

On the one hand, we are talking about education’s shifting goals and mandates. Yet, how we are doing on the existing goals of education is still a question. When can we say that a nation has an effective and inclusive higher education system?

‘Learning to learn’ and the growing challenge of AI

Recently, AI technology has made significant strides, revolutionizing various industries, including programming. Previously, programmers faced the challenge of mastering syntax and understanding coding logic. However, with the rise of the internet, the reliance on resources like ‘Google’ and advanced tools like IDEs have allowed programmers to shift their focus from memorizing syntax to comprehending coding concepts.

Now, with the introduction of AI tools, the landscape has evolved further. The comprehension aspect has become more abstract, requiring coders to communicate the desired outcome effectively rather than executing tasks directly. These advancements in AI are shaping all professions, emphasizing the importance of articulation and problem solving skills in conjunction with technical expertise.

What AI can and cannot (yet) do will fundamentally shift a human’s role and what they will be required to do. Organizations will now look to hire those who can collaborate well with AI and learn new things quickly, as what humans will be needed to do will shift continuously and faster than ever.

While the importance of twenty-first-century skills like communication skills, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity have been discussed since the turn of the century, the advancements of the last few months have put the need to focus on them with an urgency like never before. As AI consumes the more mechanical aspects of work, these humane aspects will remain the domain of humans, and humans will be expected to do more of these.

Even these skills may not be eternally safe from being made obsolete by AI. In this scenario of uncertainty, only an educational response is not sufficient. We will need a political and economic response to the challenges that will come up due to these shifts. However, it is also certain that there is a pressing need for education to adopt ‘learning how to learn’ as a fundamental goal to be effective for the individuals receiving it.

- Is it when a large percentage of its population can access higher education?

- Or Is it when its citizens can also be problem solvers and innovators who can and want to solve the challenges their communities and society face?

On the access front, India has done a lot of work in the last two decades. A higher education system is considered elite when the Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) is below 15. It is regarded as an egalitarian, massified system, when it crosses 50. In the last 15 years alone, India has almost doubled the number of people accessing Higher Education. India’s GER in 2008 was a little less than 15. We increased our GER to close to 28 in 2023. And we are targeting a GER of 50 by 2030. In absolute numbers, at India’s scale, this is a significant achievement in itself.

However, is this rapidly massifying higher education system of India effective? Most of us probably know someone with a college degree or higher, who could not secure a job that can pay them even a starting salary of fifteen to twenty thousand rupees per month, when they finish college. Research has validated this, as multiple reports are talking about the abysmal employability rates of Indian graduates.

While we increase the reach of higher education, is this education preparing people for today’s careers, let alone preparing them to learn independently or be problem solvers? Excluding the top 1 to 10 percent of college graduates, the answer is usually an unfortunate but clear no. The remaining students spend precious time, money, and energy going through the motions of higher education, in the hopes of upward social mobility and financial agency at the end of the exercise. Still, they are often left disappointed at the time of graduation.

In this scenario, is it prudent to keep increasing the reach when the scale leads to further loss of quality? The logical answer would be no. However, can we as a society afford to not increase the reach of higher education to those communities who might need it even more now, given their current line of work might be the most vulnerable to being made obsolete due to advancements in AI?

This dichotomy arises when we see inclusion only as a function of access rather than design. In such a scenario, the two objectives – effectiveness and inclusion – always have to compete for resources. It might be time to reinvent higher education processes that are effective and inclusive by design and hence lend themselves to scaling well. It might be higher education’s moment to do the equivalent of “inventing the car as opposed to keeping trying to make the horses go faster.”

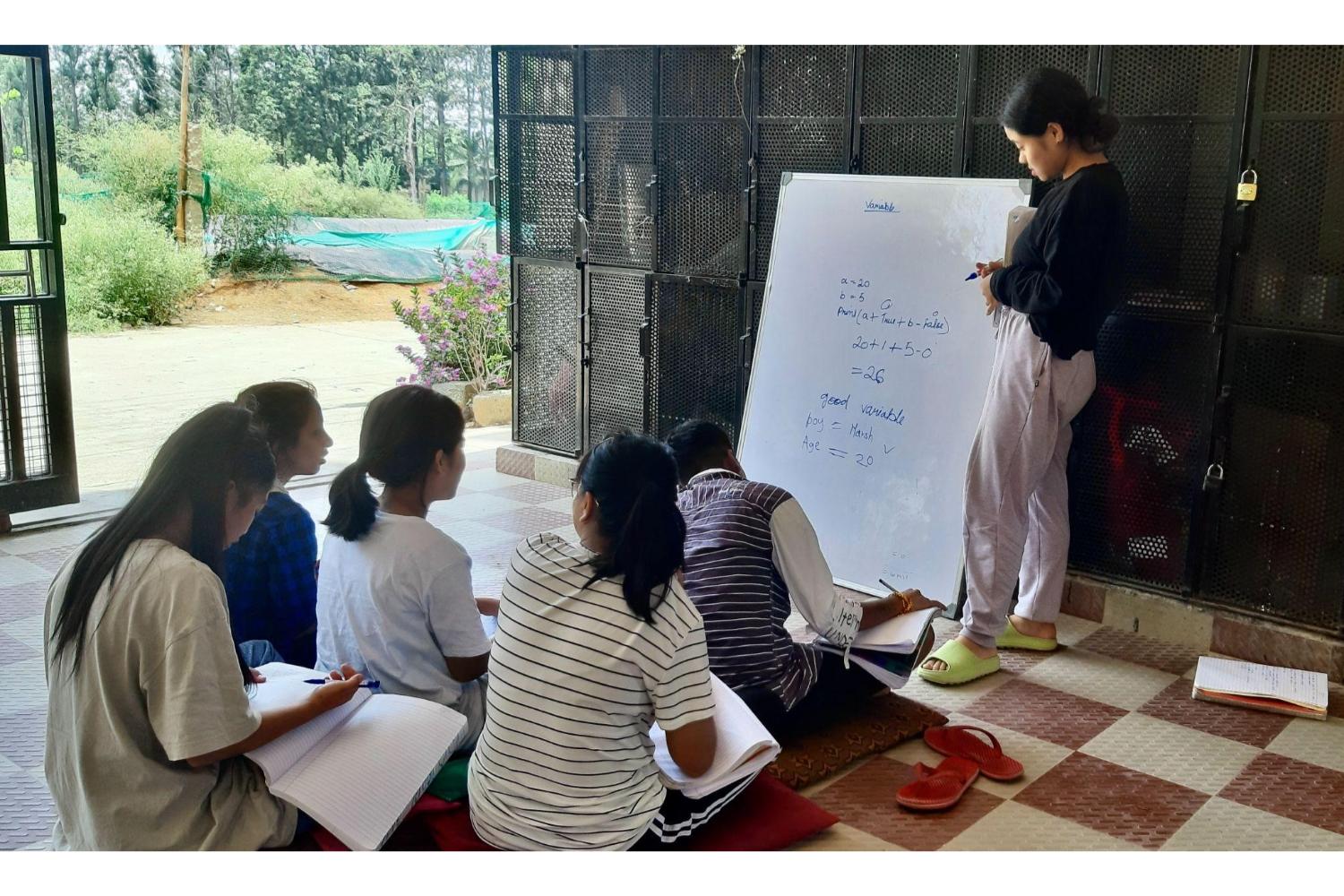

At NavGurukul, we have reimagined a learning model designed to be inclusive and effective. Through this model, we have trained girls from marginalized communities who have just finished 10th grade to learn to code and get a guaranteed job in tech through just a 12-15 month-long intervention with them. A key ingredient to making this happen has been to switch from a classroom-based model (usually followed in education) to a self-paced, peer-led learning environment.

To better understand what we mean by this, let’s look at the journey of Rafat (name changed to allow anonymity), an alumnus of NavGurukul.

Review of an alternative, simultaneously inclusive and effective, approach to learning

Rafat grew up in rural Odisha and attended a government school in her village.

Soon after she finished 10th grade, her family started considering her getting ready for the tailoring trade (what her mother knew and did). Once set up as a tailor, her family planned to get her married soon after, as they genuinely saw that as the best possible outcome for her.

Studying further required money that they did not have, and time that she could better use to learn to tailor and start working as a tailor, and get married. There was no clear pathway to a better financial or social outcome through education that they could see. Hence, they saw little to no point in continuing her formal education.

Rafat was associated with a not-for-profit through her school. She found out about NavGurukul through them. She learned that NavGurukul offered a 12-15 months-long residential program that she could attend for free, learn to program there, and get a guaranteed job in tech with a minimum starting salary of INR 20,000 at the end of the program. The program was accepting girls who had finished just 10th standard and didn’t require any further formal education. Rafat decided to apply for the program.

The first step was to take an online test that she could easily take whenever she wanted. This allowed her to start immediately, instead of waiting for next year. If she had to wait till next year, she might not have been able to apply. By then, it would have been too late for her, as she may have already become dependent on her tailoring income or be already married and may even be expecting a child. The fact that the program was free, accepted students with just a 10th standard certificate, and allowed them to start on a rolling basis, were all needed for her to be able to participate.

Rafat cleared the cut-off for the online test, which tested her on only 6th-grade English and 8th-grade Algebra. She then had two more interviews on a video call with the NavGurukul team and students, which she could take from her phone as well, without needing any permission or extra support from her family. The test allowed her to retake it (still free!) in case she failed the first time. This also encouraged her to try without it being high stakes and without fear or repercussions of failure.

When she got selected, Rafat could decide to go to NavGurukul’s campus in Pune, even without full support from her family, as she didn’t need them to pay any fees for her. She believed that if she succeeded, her family would come around. However, right now, she needed to be able to bet on herself.

Once on the NavGurukul campus, she learned that the students lived like a community, and self-governed all aspects of campus life. There were elected councils to care for different parts of campus life, such as kitchen management, facilities, discipline, etc. Participating in community meetings and working with peers forced her to learn to speak, speak up, negotiate and create friendships (and alliances!). She gained empathy, learned to understand and appreciate varying perspectives, and to live and collaborate with people from across the country.

We found that this community living provides the learners with ample opportunities to learn and practice twenty-first-century skills in a practical hands-on manner, that no other classroom experience could replace. Even after many years of graduation, our students feel and express gratitude for what they learned through this experience and how it has helped them tremendously in their careers.

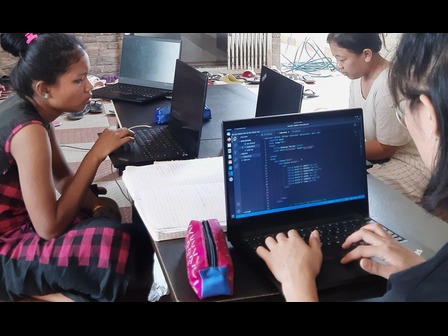

Rafat also learned that the learning style on campus differs significantly from what she has experienced in school. There are no regular ‘classes’ at NavGurukul. Instead, she received a laptop and some basic instructions on how to get started learning on her own. The curriculum started from the basics, and allowed her to move through it at her own pace.

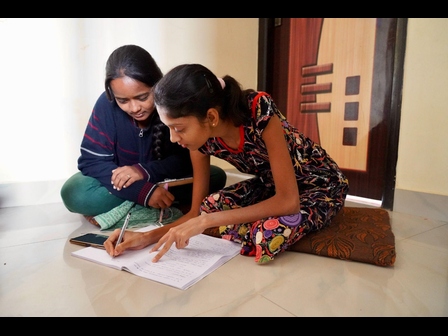

She was assigned a peer mentor who would spend some time with her every day to ensure she had not gotten stuck anywhere and used her time well daily to move forward in her learning journey. She found out that the peer mentor was a student just like her, who started her learning journey just a few months before her.

Since her mentor seemed to have been able to learn through this system, and came from a similar background as herself, it allowed her to trust the process and go with it, even though she was skeptical about how she could learn without classes and without someone teaching her everything.

She also saw that there were team facilitators who solved doubts, as needed, in a personalized manner, for each learner on campus. They also ensured that each learner was moving forward in the curriculum week by week. The technical curriculum enabled her to learn programming, starting from the basics of math, logic, fundamentals of programming, and Javascript.

In parallel, the life skills curriculum enabled her to improve and practice her English, communication, collaboration, and critical thinking skills. There were sessions that were designed to get students to gain confidence and understand gender, environment, financial planning, and other crucial life skills. She also got exposure to a world of inner work practices that helped her peers, and herself, manage stress, emotions, trauma, and other limiting belief systems and behaviors they may carry with them. Through it all, she forged friendships, which have become her support system and network for personal and professional things.

Since she was not learning through a classroom, but through a self-paced learning model instead, she could take time to look up words in English that she did not understand. Hence, English did not become a blocker for her to be able to learn to program, while still enabling her to improve her English in parallel.

Seven months into her time at NavGurukul, Rafat got ill and had to go home for bed rest after a surgery she had to undergo. When she had fully recovered after three months, she could come back to NavGurukul’s campus and get started from where she had left. While she had initially struggled with self-paced, peer-led learning, she was now grateful for it, as it was because of self-paced education she could continue her course, instead of having to drop out or come back next year and start again.

Once back, she finished her learning journey, traveled a little to other NGOs in Udaipur as a part of an exposure trip, and received an internship offer from an IT MNC, which paid her a stipend of INR 22,000 for the internship and a salary of INR 30,000 per month post the completion of the training.

She has been working with that MNC for four years, earning a salary of INR 11 Lakh per Annum. She has learned many things while on the job, and continues to upskill herself to stay relevant. She has successfully pulled her family out of the financial crisis they were stuck in, when she first joined NavGurukul. She is not married yet, and she and her family are in no hurry to change that. She is just 22 years old, after all.

In more ways than one, the flexible, self paced learning environment enabled policies that could cater to Rafat’s needs ensuring that she could sustain and finish her learning journey, while ensuring that what she learned was meaningful, relevant in the industry, and learned with understanding.

Challenges in doing free, self-paced learning

The mentor-mentee system works best only when the pair is emotionally aligned and is deeply committed to each other’s success. There are challenges in pairing and keeping these relationships solid and ensuring that the learning momentum doesn’t get hurt when there is a rupture in some of these relationships because of practical reasons like, say, the mentor had to go home or got placed and left campus or when there is a misunderstanding of sorts between the pair.

We have found that the answer lies in keeping everyone rooted in a community of support systems rather than working just in pairs. Even the periodic changes in the primary pairings and learning to adapt to that change is a necessary learning experience when preparing for the real world, where situations like this arise in abundance.

However, managing this is indeed critical and not trivial. Still, we have found that these are worthy challenges to pick up, when solving for designing a system that is both inclusive and effective. The domains of behavior science and pedagogy have great recommendations to make that can help tackle this, if one commits to the process.

Another question we get asked often is whether students value this when it is free. Even we as a team, when sometimes unable to get some students to take ownership of their learning, have ourselves wondered if charging for this will make them more serious about their education.

However, we have collectively arrived at the answer that there are ways in which we can design policies and culture on campus that encourage sincerity and dedication, irrespective of whether they have paid for the program or not.

Charging money, while it looks like an easy answer sometimes, is not always the best answer. Motivating someone to do something, not just because they have paid for it, tends to be real, intrinsic motivation.

Even if it is true in a small percentage of cases, where fees could have encouraged more sincerity faster, we currently choose to keep it free because a residential structure does allow us to work on other ways of maintaining sincerity, while enabling us to serve those who genuinely can’t pay.

Instead of charging upfront, if we encourage a culture of pay forward, it has several benefits. It makes our students and, by extension, our society, more giving-focused. More importantly, in this model, educators and institutions must focus on delivering quality learning outcomes.

Using this pedagogy and model, NavGurukul has placed more than 600 students, such as Rafat, in high aspiration tech careers. We have already scaled up to 7 centers across the country, 4 of which are in partnership with state governments. We are in the process of opening more centers.

In addition to programming, we have also started piloting management, design, and education courses. We have found that this pedagogy can be applied not just in learning programming, but across many, if not all, domains in higher education.

Can we scale this model of learning?

The question is not whether NavGurukul or even these residential centers as an idea can scale or not. Should we and can we scale the pedagogy of self-paced, peersupported learning to more higher education spaces across states, domains and levels of educational institutes – at ITIs and in IITs? Will it help improve the effectiveness and inclusiveness of our higher education? What will it take? What costs shall need to be paid?

First and foremost, we will need to have a paradigm shift in what we see as the role of the teacher. Right now, a teacher is supposed to be a subject matter expert, a pedagogical expert, a social-emotional support system for the learner, and an assessment expert. In many cases, she is sometimes an administrator as well, who has to shoulder responsibilities in infrastructure, HR, Finance, parents management, etc., as and when needed. Not a teacher; we expect them to be magicians.

The pedagogy of self-paced learning allows us to unbundle all of the above responsibilities and distribute them amongst peers, mentors, and external/ volunteer subject matter experts, to reduce the burden on the teacher, who can now be thought of as a facilitator instead. Their role then can be reenvisioned as ensuring that all of this comes together for the learner, to be able to have a conducive learning environment.

This is not a trivial shift for India’s scale. However, it might be a welcome one. The lack of well-trained teachers who can be SMEs and good educators simultaneously is one of the top challenges in increasing the reach and quality of the existing higher education system. Similarly, we must shift how we conduct assessments and what counts as outcomes.

What about the cost? Is this model expensive? Can it scale at a country level?

Given that it is self-paced, and has peer support, the model allows much more frugality than the existing learning models. It also allows engaging the industry in a volunteering/ paid engagement model in a structured way, as they can come in for the subject matter expertise, enabling learning to be practical and relevant, while still keeping the costs frugal. Once they get into jobs, the amount the learners pay in taxes alone can be a massive bonus for the economy. Hence, there is an incentive to invest in this.

Additionally, we can bake in pay forward as a part of the culture, where each student supports someone else’s education, once they have achieved some financial security. Instead of upfront and exorbitant fee structures, these models can make institutions accountable for learning. They can make education accessible to India’s most vulnerable communities. They can enable India to unlock its tremendous potential to be the global talent capital.

Going down this path will require much more thought and rigorous research. Still, we submit that this learning approach be considered to free up access to quality learning from the constraints of location, economic and pedagogical barriers it is currently caged in.

Imagine a world where any person, coming from any caste, class, age, or region of the country, has access to clear pathways to high-aspiration careers and skills, which allows them to start from where they are and are designed keeping their constraints in mind, and will enable them to learn and succeed, at their own pace.

An Invitation

If you have any comments on the article or would like to partner with NavGurkul in any way, you may reach out to Nidhi at her email id given at the end of this piece. NavGurukul works with girls from marginalized communities to get them to learn digital economy skills such as programming, design, etc., and place them in guaranteed jobs in tech at the end of the intervention.

The NavGurukul team would love to hear from you, if you can help them reach out to girls from marginalized communities, who would like to take advantage of their free residential program, or if you want to join NavGurukul (people are everything!), or if you or someone you know would like to hire NavGurukul’s students or alums.

🔏 You have 1 message # 497. Read > https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=60a56c6cfe384951551a309bfd314a61& 🔏

January 12, 2025kvmgxf

📝 Ticket: Transfer №DA11. NEXT =>> https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=60a56c6cfe384951551a309bfd314a61& 📝

December 31, 2024f00ts0