Tracing the contours of educational assessment – Lessons from the past and directions for the future

In her context setting piece, Aanchal Chomal traces the contours of educational assessment in terms of its history; she also discusses the policy imperatives related to assessment in independent India and draws out implications for practice in our present context.

One of my earliest projects at Azim Premji Foundation (APF), when I joined in 2006, was to assess students under the organization’s flagship program called the Learning Guarantee Program. Among its many objectives, a key one was to ensure ‘competency-based’ education and learning in schools, and ascsertain the extent to which schools were doing it. I was assigned to a remote block called Gadarpur in the district of Udham Singh Nagar in Uttarakhand. My task was to administer an EVS (Environmental Studies) tool orally with students of classes 3 and 5. The tool was aligned to the state syllabus. It had a marking scheme with suggestive responses to the questions.

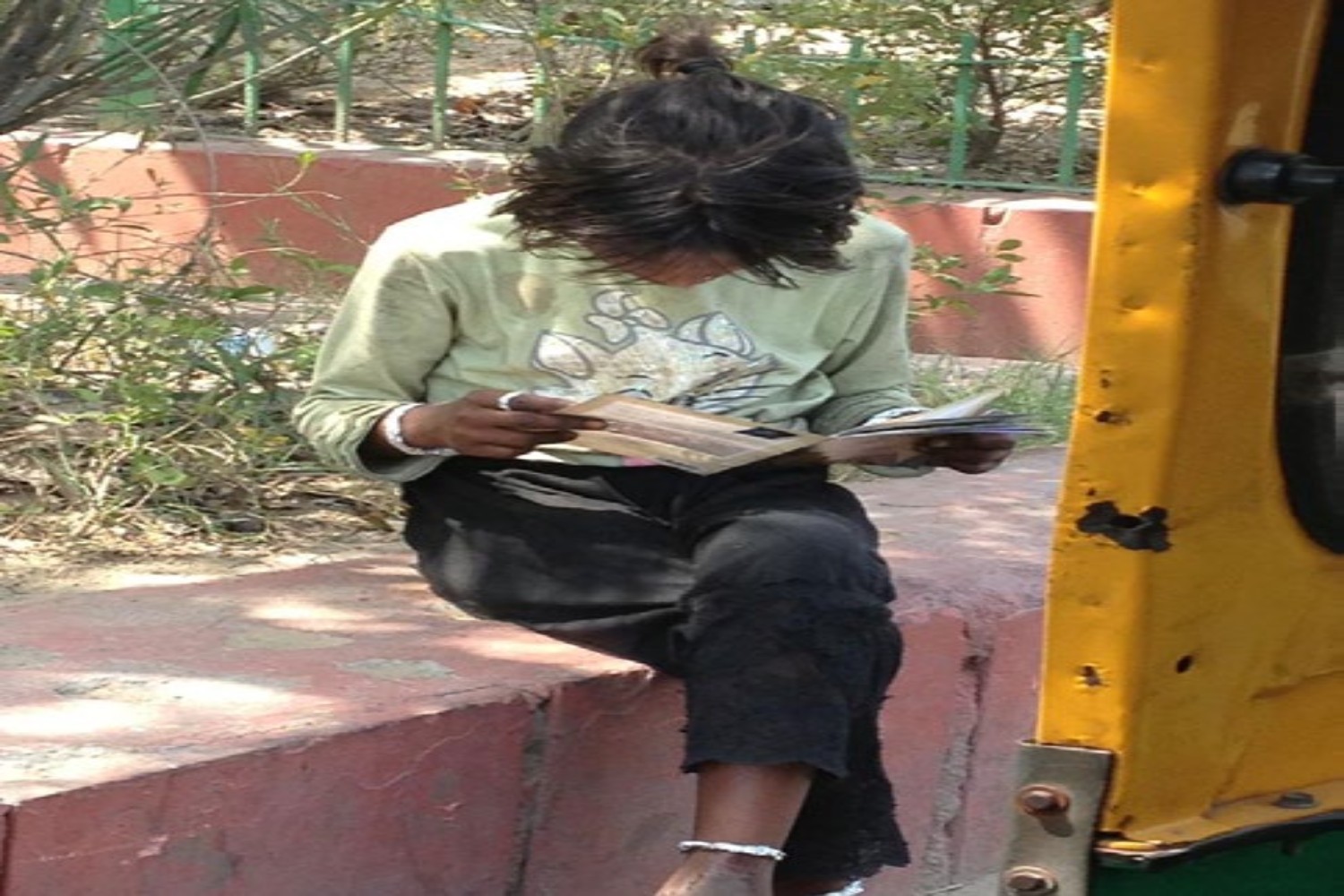

The assessment was administered with one child at a time. So, I sat with this child, a young girl of roughly 6-7 years of age. After a few informal conversations began the administration of the tool. The first question was about the child and her family. The next one was on plants and animals. The third one was on sense organs.

I showed the flashcard of various sense organs to the student. My task was to ask the simple question, “What is this used for?” So, I showed the picture of a pair of eyes to the child and asked her – “ye kis kaam aati hai” (“What is this used for?”). The suggestive responses in my marking scheme were – to see; to read; to draw; to write; and so on.

When I asked the child this question, she looked at me for a while and then said, “Didi aankhein rone ke kaam aati hai” (“Eyes are used for crying”). I looked at the child for some time. I was not able to figure out why she had given me such a response. I was, of course, left speechless.

There were several thoughts going on in my mind. What may have been the childhood of this 6-7-year-old child to respond to this question in this way? Did she need help? Why did she not think of the obvious responses? What sort of family did she belong to? Did her teachers give adequate attention to her in the class? The list was endless.

What I do remember is that I could not ask her any further questions from the EVS tool that day. But yes, I did spend the next one hour talking to the child to know her as a person and not just a respondent of my survey tool. That day I came back realizing a fundamental characteristic of assessment – every assessment reveals to you something about the child which you did not already know of. And that helps and directs you as a teacher, as a mentor, and as a guide to the child. The realization that assessment plays one of the most pivotal roles in student learning was as clear as it could be.

However, in our country, the assessments being practiced currently across various stages and diverse kinds of educational institutions are far from this. There is a predominance of tests and exams as a sieve to filter and rank the students. This process is coupled with the fear, anxiety and stress it causes among students, teachers, and even parents. In the past few decades, one has also heard policies and programs such as Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) and other forms of assessment that are informal and less stressful.

One often wonders why is there such a massive dichotomy in the usage and purpose of assessment? On the one hand it is used as a sharp, high-stakes measure of achievement that leads to far-reaching life choices. On the other hand, it is also supposed to play a developmental and constructive role in students’ lives. We often refer to these as the evaluative and formative function of assessment. How do these two seemingly dichotomous conceptualizations of assessment co-exist?

The evolution of educational assessments

There have been several attempts to trace the history of education and in doing so the history of examinations and assessments. It will be important to mention at the outset that this history is rather irregular and unsystematic. One of the oldest traditions of assessment was the oral examinations characteristic of medieval education, that was primarily being imparted in monasteries and convents.

To know something was to know it by heart and recite it as the proof of learning. The medieval monk was expected to learn Latin grammar to learn Latin texts. The study of grammar meant learning by heart famous grammars dating from the Roman Empire, or simpler textbooks aimed at beginners. These grammars were written in the style of questions-and-answers. Reproducing them in their exact form was expected. (Wilbrink, 1997)

Another very popular form of assessment was that of written examinations. Imperial Chinese examinations conducted for selection in civil services are one of the oldest documented written exams conducted periodically in designated centers. In colleges, as an outcome of various reforms, faculties of both Oxford and Cambridge decided to improve their curriculum and introduced frequent examinations in a variety of topics. The first clear indication that written examinations were used for admissions and graduation is found for the year 1702. The exams of this era were almost exclusively essay questions emphasizing factual recall; one extant example shows eight questions each in history and geography, and six in grammar, primarily Latin and Greek (Arthur, 1987).

In the school systems in Europe, as textbooks for the grammar schools became grade specific, exams became more regularized. The Jesuits found this system of examinations quite appropriate to their needs and it rapidly spread across Europe. Examinations were seen as the best way to focus the students’ academic efforts, and to set criteria.

In the United States, somewhere around 1845, following Horace Mann’s recommendations of written examinations, testing was incorporated in primary and secondary schools. The first examination was administered in Boston that year. Within thirty-five years, promotion from grade to grade was judged as success or failure. This was based on scores calculated as a percentage, based on performance on a written exam (Arthur, 1987).

While formal systems of examinations were mushrooming, the system of examinations was also being criticized. It is documented that students at Yale rebelled against exams as early as 1762, as it perpetuated ‘cramming’ and came at the cost of scholarship. Faculty at universities struggled to develop tests that balanced content, memory and skills. In 1881, the superintendent of schools in Chicago expressed strong objections against testing for grade-level advancements and suggested that teachers and principals were better suited for doing this. By the end of the nineteenth century, in some parts of the world, testing had gained a bad name. Where testing was still used, teachers were ‘teaching to the test,’ with a lot of drills and practice.

Besides systems of assessments being adopted in schools and universities, one of the major developments around assessments came with advancements in the theory of measurement and testing with the introduction of intelligence tests. The science of educational testing and measurement was getting more and more sophisticated, with rigorous statistical methods and tools. Advancements in psychometrics added more rigorous methodological procedures in standardized test designing and its analysis.

Classical test theory, and in more recent times Item Response Theory (IRT), came to be the accepted gold standards of standardization and test quality. It was recognized that in high-stakes tests, where data generated is used for far reaching policy changes, rigorous standards of quality in test design must be followed. Mathematical models and theories such as IRT and several more began to be used to generate information that provides better understanding of the test instruments and student achievements.

Particularly in the context of schools and how one sees the process of education, assessment inside the classrooms underwent changes with paradigm shifts in learning theories. From the behavioristic paradigm of teaching being viewed as transmission of knowledge to the constructivist paradigms of children constructing their knowledge using their experiences in real life contexts, there were several pedagogical transformations that were being suggested to make classrooms meaningful spaces to learn.

It comes to us as no surprise that assessment and evaluation processes that teachers used in classrooms were also being analyzed for their efficacy in the teaching learning process. In the seminal work ‘Inside the Black Box,’ for the very first time, there was compelling evidence to indicate that classrooms where teachers were integrating assessments in the day-to-day teaching learning process, using a host of formal and informal methods, were showing better student learning (Black and Wiliam, 1998).

We, thus, entered the era of ‘formative assessments’ being thrust upon as a policy reform across several countries of the world including India. Approaches of assessment ‘for learning’ and ‘as learning’ began to take shape. A wide range of ‘authentic assessments’ such as projects, role plays, demonstrations, experiments, portfolios, etc., came into the picture.

The preceding discussion clearly suggests that there is a field of educational assessment, which is fundamentally multidisciplinary and the contours of which are still evolving. The field is being enriched by advancements in education, psychology, statistics and psychometrics.

It is also very clear that the clout of examinations weighs heavily upon this field. Therefore, disproportionate weightage is often given to various stages of test paper designing and methods to make the test instruments valid and reliable.

It is also evident that the evaluative function of assessment (assessment being used for ranking, promotions, measuring achievement, and so on) and the formative function (assessments being used for understanding student learning, identifying their misconceptions, and modifying the teachers’ strategies) of assessment are both equally prevalent. Very often, the former is prioritized over the latter.

Scoping the field of educational assessments for practitioners

It is very important to scope the field of educational assessment for practitioners, primarily the teachers. One of the interpretations of the word assessment, which resonates with its formative purpose, is its association with the Latin word ‘assidere’ which means to sit beside. For all practical purposes, the practice of assessment is to sit beside the learners to help them learn.

‘Educational assessment’ can be said to broadly include the collection and interpretation of data or evidence which provides understanding about learner needs and effectiveness of teaching process and classroom practices. Eliciting evidence of student learning, analyzing and interpreting this evidence, and acting upon it, are fundamental processes in assessment. Teachers and students are both key actors in these processes.

The definition provided above makes assessment essentially a cyclical and iterative process, which is quite organic in nature. What are some of the pre-requisites to enable this process in a classroom?

Deep understanding of learning standards: This includes a comprehensive picture of the curricular goals, competencies, and learning outcomes across the stages of schooling.

Understanding the learners and how children learn: Fundamental to this process is the familiarity and appreciation of the learner’s context, their academic and nonacademic needs, and pedagogical knowledge. Understanding the ways in which diverse learners engage with a concept in a subject is also important. For instance, how do children learn to count, or learn to read? Which pedagogical strategies work? Which don’t?

Capacitating teachers to design and use quality assessments: One of the essential pre-requisites for good quality assessments is to capacitate teachers to design and use their own assessments. To enable this, teachers can be provided with professional development opportunities or meaningful integration of assessment practices in teacher preparation programs.

Landscape of assessment in India

If we look at the current landscape of assessment in India, there are at least four distinct purposes for which assessments are being used. These are assessments for certification purposes like the Board exams. There are assessments that are being used for selection, such as IIT-JEE, CLAT, CAT, CUET and NEET. Then there are the assessments for measuring systemic health, such as NAS, ASER, large-scale state level assessments like Gunotsav (Gujarat), Pratibha Parva (Madhya Pradesh), C-SAS (Census State Achievement Survey-Karnataka), and so on. Finally, there are the assessments that support student learning in the classroom, e.g., processes like CCE and other formative assessments.

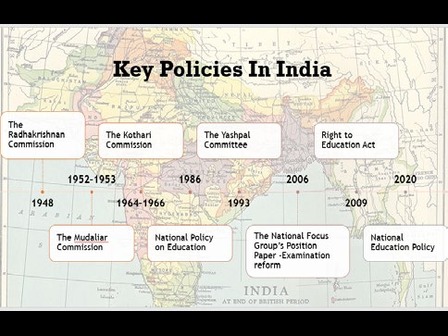

If we look at the history of assessment reforms in India, it is worthwhile to revisit some important policies and programs in the post-independence period, which discussed the matter of education and specifically examination reforms in India. This will help us understand the current priorities in assessments and their historical antecedents.

Radhakrishnan Commission Report: This is also popularly called as the Report of the University Education Commission. This Commission was set up in postindependence India (1948-49). It made various recommendations for examinations that are relevant even today. The report stressed the need for making examinations better aligned to educational aims (the matter of validity), and introducing scientific processes to increase the validity and reliability of exams.

Recognizing the evils that surrounded examination systems, the report states, “In our visits to universities we heard, from teachers and students alike, the endless tale of how examinations have become the aim and end of education, how all instruction is subordinated to them, how they kill all initiative in the teacher and the students, how capricious, invalid, unreliable and inadequate they are, and how they tend to corrupt the moral standards of university life.”

In defining the quality of a good examination, the report suggested five essential conditions: Validity – it should measure what it intends to measure; Reliable – it should efficiently measure what it does measure; Adequate – represent the content sufficiently so that the scores indicate performance in the areas measured; Objective – minimize opinions, bias, and other subjectivities; Easy to administer, mark and interpret.

Among the above five conditions, the commission’s report elaborated on the importance of objective testing and the need for eliminating bias and subjectivity, improving time and efficiency in the testing process. Yet another interesting suggestion of this commission was to give adequate credit to performance in classwork. It recommended allotting nearly 1/3rd of the marks of each subject to work done during the academic year. This aimed to reduce the stress of too much dependency on a one-time summative exam. Though the report did not discourage essay type of question, the reasons for sustaining it was more operational – easy to design and administer, rather than its value to assess certain disciplinary areas that may not be comprehensively assessed using objective tests.

Mudaliar Commission Report: This is also known as the Report of Secondary Education Commission (1952-53). It stressed on the holistic development of students and the need to look at social, emotional, intellectual and physical development of children, along with the academic abilities. It recommended the need for examinations in all these areas and reduce dependency on single exams. The idea of multiple assessments that are ongoing and comprehensive came into the discourse.

Maintaining records of students’ work, giving adequate importance to internal examinations, and making it a part of the public exams were some of the key ideas proposed in this policy. It stated that such records would provide inputs for “growth of his interests, aptitudes, and personality traits, his social adjustments, the practical and social activities in which he takes part. In other words, it will give a complete career.” The nature of such a record was quite like what we currently call a ‘portfolio.’

The policy also criticized the system of marking using percentiles or scores out of 100. It raised very pertinent questions on any exact measurement among a student who scores a 45 vis-à-vis someone who scores a 47! The policy recommended replacing such marks with a 5-point grade scale with A being excellent, B for good, C for fair or average, D for poor and E for very poor. In specific cases, where a distinction had to be made for the purpose of scholarships or prizes, the scale could be sharpened further.

On the matter of public examinations, the report was way ahead of its time. It recommended that students should take only one public examination. Even the final public examination need not be compulsory for all students. It could be replaced by a school certificate that comprehensively provides the students’ cumulative progress. Yet another striking feature of this commission was the trust it placed in teachers and their ability to judge the student.

The report acknowledged that, “The only way to make a teacher’s judgement reliable is to rely on them! In the beginning there may be stray cases of wrong judgements but in the long run they will become more reliable and trustworthy”. The report also cautioned against the trend of evaluating a teacher’s success based on their students’ performances. Calling this as ‘unfortunate,’ the report quite sharply observed that the practice of headmasters presenting their school’s results of examinations was quite like ‘profit and loss account being presented to shareholders of an industrial concern!’ Extending this criticism to the work of the teacher, the report observes that, ‘to judge the work of a teacher by the percentage of passes of his pupils in the examination is to keep alive the old and exploded system of payment by results.’

Kothari Commission and NPE 1968: The year 1968 saw the first National Policy of Education (NPE), based on the recommendations of the Kothari Commission (1964-66). NPE 1968 was one of the first and most comprehensive policies discussing education across all stages from primary to secondary. Echoing the ideas of the two earlier commission reports, and particularly the Mudaliar Commission Report, the policy stressed that evaluation is a continuous process and should involve more than just certifying students.

The report reiterated the conditions of good assessment, as stated in the Mudaliar commission report, adding ‘practicability’ as an additional one. Critiquing the overdependence on ‘written exams,’ it suggested improving their quality to make them more valid and reliable. It also emphasized the need to improve the technical competence of paper setters. This was envisaged to help question papers test for certain important learnings apart from knowledge acquisition. These include the capacity to apply knowledge and problem-solving abilities. The report observed that there are several aspects of students’ growth that cannot be measured by written exams, and that other methods such as observation, oral tests and practical, were useful and essential. The need for improvement and better reliability in these methods was also emphasized.

On the matter of external examinations, the report suggested attaching internal assessment results of students along with their external exam results. Students were to be given the choice of either attending an external examination for certification or take the school level certification. It recommended the first external examination to be held at the end of the 10th standard and the second to be held at the end of the 12th standard.

NEP 1986 and POA (Programme of Action) 1992: Within less than two decades, there was yet another National Policy in 1986. Based on the review of NEP 1986 by the Ramamurthi Commission, the 1992 POA was suggested. One of the interesting observations made by the committee was that the idea of detention versus nodetention suggested in the NEP 1986 has led to a negative framework.

To avoid that, it recommended a positive concept of continuous, disaggregated and comprehensive evaluation. The report also suggested the need for engaging with teachers on the ways of doing such a continuous evaluation for quality improvement. Such a continuous and comprehensive evaluation was suggested for both scholastic and non-scholastic aspects. This policy also emphasized the need for grades instead of marks.

On the matter of public examinations, the policy laid out that Boards should suggest expected levels of attainment at classes V, VIII, X & XII, and prescribe learning objectives corresponding to them. It suggested detailing out design parameters such as content area, weightage, question types and objectives of teaching-learning, prior to setting question papers. A modular pattern of offering courses with the provision for clearing board exams in parts, in conformity with the modular pattern of courses, was recommended.

At the systemic level, the idea of establishing a National Testing Agency for organizing and quality control in nation-wide tests was made. Soon after the POA, the Yashpal Committee Report, 1993, popularly known as ‘Learning Without Burden,’ also raised concerns about the prevailing examination system. It recommended modifications in the types of questions in the 10th and 12th Board examinations, to relieve students of unnecessary stress and anxiety.

National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005, and the Position Paper on Exam Reforms: NCF 2005 brought about several long-term principles that were much needed in visualizing assessments differently. Stating the purpose of assessment, the document rightly stated that, “Education is concerned with preparing citizens for a meaningful and productive life, and evaluation should be a way of providing credible feedback on the extent to which we have been successful in imparting such an education.”

To do this, it suggested the need to orient teachers on a host of areas, including parameters for assessing and techniques to assess. The idea of using assessment during the teaching, such as learning activities that aid in ongoing observational and qualitative assessments of children, was suggested. In areas such as sports, arts, yoga, etc., which cannot be assessed using marks, the NCF suggested markers such as participation, interest, and level of involvement, and the extent to which abilities and skills have been honed. These were expected to help teachers gauge the benefits of what children learn and gain through such activities. Asking children to self-report on their learning was also suggested.

NCF 2005 also made specific suggestions on the types of questions that are set for assessment. Open-ended and challenging questions that go beyond the textbook were suggested. It also stated that adequate attention should be paid to teachers’ capacity building in this area.

The consequent ‘Position Paper on Examination Reforms’ lamented the issues of present-day examinations. It foregrounded the need to make specific changes in the quality of question papers. It suggested defining competencies, setting difficulty levels, using good quality MCQs, and detailed marking schemes, etc.

The paper also echoed the recommendations of earlier committees and suggested the use of multiple modes of assessment. Making board exams optional was yet another important recommendation along with greater choice of subjects and a 3-year window to pass the exam. CCE was defined as a school-based system of evaluation, which is continual or periodic (before and during instructions) and comprehensive (including scholastics and co-scholastics areas), using multiple modes of assessment.

RTE, CCE and No-Detention Policy: After the recommendations of NCF 2005, yet another landmark was the passing of the RTE Act in 2009. CCE became a reality as a policy reform, along with its twin policy of NoDetention. Across the various states that APF has worked in, there was an echoing sentiment that CCE was ‘old wine in new bottle,’ and that we have been doing CCE forever. Yet another common reaction was the load of documentation and filling up of formats, which was quite overwhelming for the teachers.

One of the most significant lacunae in CCE was that it was seen as an ‘implementable program’ or ‘scheme’ of the government that is associated with a series of routinized processes. There was inadequate conceptualization of the kind of reforms in pedagogy and assessment that it demanded. In most cases, it were the class 10 CCE guidelines issued by CBSE, which were used to frame models for CCE, and for state-level guidelines for the elementary classes.

‘Continuous’ was often misconstrued as periodic tests. It was operationalized as a series of shorter tests, adding stress and burden to the learners. One of the biggest confusions that CCE implementation created was the misunderstanding that formative and summative assessments can be segregated based on the type of tool being used by the teacher. In making a distinction between formative and summative assessments, it was the mode of assessment rather than the objective that was the basis of the division.

Consequently ‘activity-based’ assessments such as projects, role plays, and portfolios became tools of formative assessment. The bulk of summative assessments continued to be paper-pencil test, with very little change in the nature and type of questions asked. The term ‘comprehensive’ was also subject to multiple interpretations – co-curricular, co-scholastics, personal and social qualities, with inadequate preparation on how to assess these. Therefore, what we have seen over the last two decades are various models of formative assessments that are nothing short of summative. The ideas of FA 1-FA 4 and SA 1 and 2 came into vogue. Even students were found saying that they had their ‘FA- 2 exam!’

While school systems, teachers, parents and students were grappling with all this, there was also an ongoing debate whether the No-detention policy (NDP) was doing more harm than good to the students. There were sentiments on the ground that no exam meant no learning, and that both students and teachers were becoming nonserious about learning. There was a recurring debate on whether fear and punishment are necessary for learning. It comes to us as no surprise that in 2017, after recommendations from a CABE committee set up to measure the implementation of CCE and other consultations, the NDP provision of the CCE was rolled back. States were allowed to detain students at the elementary level, after a couple of re-attempts.

NEP 2020: It is in this backdrop that the most recent education policy has come into existence. At the outset, the policy acknowledges the issues with present day assessment practices. The policy highlights the roadmap for transforming the culture of assessment towards learning and development. The overarching focus is be on regular, formative, and competency-based assessment, testing higher-order skills, such as “analysis, critical thinking and conceptual clarity,” and their application in real-life situations. By focusing on competency development instead of content memorization, it promotes testing core competencies and foundational skills to lighten academic pressure, making assessment stress-free and non-threatening, and curtailing the mushrooming of coaching classes. The policy also suggests a 360-degree holistic progress card, in line with the comprehensive development suggested by earlier policies.

NEP 2020 also suggests introducing standardized/large-scale assessments in the critical stages of transition, i.e., grades 3, 5 and 8 to avert the pressure from board examinations and track progress at various levels of the school. It encourages the results of these large-scale assessments to be used only for developmental purposes and for continuous monitoring and improvement of the schooling system.

At the institutional level, the policy suggests setting up a National Assessment Centre as a standard-setting body under the Ministry of Education (MoE). It has been named as PARAKH – Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development. It is supposed to encourage and help all the school Boards in India to shift their assessment patterns to meet the skill requirements of the 21st century.

On the matter of certification exams, the policy suggests continuing with Grade 10 and 12 Board examinations. It recommends redesigning the Board exams to eliminate the ‘high stakes’ element and distribute the burden. The objective is to make them less stressful and distribute their currently high stakes across the secondary stage. It recommends giving students greater flexibility and choice to choose many of the subjects in which they can take the Board exams. It proposes to make the Board exams meaningful in the sense that they will primarily test the core capacities and competencies instead of rote learning.

Over the last 75 years, there have been much needed policy reforms in the conceptualization and direction of assessment. However, the implementation of many of these recommendations on the ground has been uneven and very often with inadequate preparation and groundwork. CCE was clearly one of them. Also, in the absence of a broader conceptual framework of the different assessments being carried in our country, practitioners often struggle to understand the kind of inferences that can be drawn from each of these assessments.

A classic example of this involves the results of National Achievement Survey (NAS). A policy maker may use the NAS results to understand the broad trends of learning in their districts, allocate funds or initiate specific programs in particular districts. However, a District Education Officer (DEO) is not expected to target schools and penalize teachers in his district for falling short in the NAS survey. Since results of NAS are reported at the state and district levels, there is no disaggregation of the data at the levels of blocks, clusters and schools.

Therefore, the survey will not give any school- specific and student-specific information that a teacher can use to take decisions for her class and her students. Even for the schools that are part of NAS, there will be no school-specific data available. Such clarity is much needed on the ground to remove the unnecessary stress caused when these surveys occur and after the results are declared.

Assessments: directions for the future

Based on the history of assessment in general, and its evolution in India in particular, there are few key lessons to keep in mind. These will be useful in efforts to transform assessment practices on the ground.

There needs to be an understanding among practitioners about the various purposes of assessment. Clarity is required on what an assessment can and cannot do, the kinds of insights it can generate, and the ways in which we can use the insights to improve practice.

Equally important is to situate assessments in the context of learning. While there may be assessment practices that we have borrowed from the past, it is extremely critical to evaluate their efficacy considering how we would like education to be for the future. Assessment must become a part of the teacher’s pedagogy. It must not function as a mechanism to assign grades, marks or ranks only.

We also need to strengthen teacher-led, classroom-based assessments. Assessments in our classrooms should become more purposive in nature. There may be the need for regular and periodic assessments, as per the school schedule and board requirements. However, it is important to ask the question whether the assessment is focusing on key competencies and outcomes or involves just memorizing inert facts? We must try and make the assessments helpful for the teachers to understand children better and self-evaluate teaching practices. Assessments’ focus must remain on the learner and not only on the product of learning.

Assessments must also become developmental and constructive. This is easier said than done, given the long history of examinations, and the kind of purpose it has served over the centuries. However, for all practical purposes, assessments should assist in student learning, not just implicitly but also explicitly. For e.g., as a teacher, one must be able to design assessments that are differentiated and target diverse learners and learning trajectories of students in their class. It should be centered around development of core competencies and dispositions that are vital outcomes of education.

Assessments can also be used to provide feedback to students. This process can help them identify their strengths and the areas that need improvement.

Classroom-based assessments should not ape large-scale assessments in design and purpose. Written exams are the order of the day. Multiple-choice questions have become popular in various competitive exams. However, it is important to realize that in a classroom, a teacher need not be restricted to only these choices. One would want students to use their own language in explaining a concept, a procedure, or any experience for that matter.

Similarly, all assessments need not be only written in their form. In the last few decades, we have learnt about various methods of assessments that are beyond the traditional paper and pencil tests. Such diverse assessments help teachers to assess a wide range of competencies and dispositions. These are otherwise impossible to assess in a written paper, or for that matter in an MCQ- based written paper.

Adequate time should be given to implement the reforms and use the emergent insights. The pressure of assigning marks or grades to every assessment task should be questioned. The focus should be on gaining reliable evidence of student learning, rather than just the progress against set criteria.

In conclusion, any system of assessment that is counter-productive to learning must be re-examined and in the long run weeded out. Educational assessment is an evolving field of study. It will continue to get more sophisticated in the years to come. Advancements in measurement techniques will progress to build frontiers of knowledge and testing procedures. However, the ‘what’ of knowledge/learning will continue to remain relevant.

These new advances that are useful for the teacher to help students learn better must be carefully curated. The teachers’ role and the assessments that they carry out in the classrooms cannot be underestimated. One of the most effective and sustainable forms of assessments will continue to be teacher-led formative assessments of their students’ learning. As practitioners working in education, it is our collective responsibility to support teachers and other practitioners in this journey.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!