The wisdom of contexts – How social interventions can listen and adapt

Our journey of nine years in Gubbachi feels a bit like Alice’s plunge into the rabbit hole of fantastical creatures – rich, constantly evolving and sometimes unexpected. We set out in 2015 (with staunch backing from WIPRO) with a humble idea of running a Bridge Program in Kodathi GHPS (Government Higher Primary School) along Sarjapur […]

Our journey of nine years in Gubbachi feels a bit like Alice’s plunge into the rabbit hole of fantastical creatures – rich, constantly evolving and sometimes unexpected. We set out in 2015 (with staunch backing from WIPRO) with a humble idea of running a Bridge Program in Kodathi GHPS (Government Higher Primary School) along Sarjapur Road in Bengaluru city. Kodathi then was a fast-growing peri-urban area full of construction sites. Now it is on the throes of being absorbed within the city limits.

The program’s goal was to help integrate children from the neighboring migrant labour settlements, into the local government school. Our community team consisted of one person who worked with families just to ensure attendance.

Children from migrant communities in the city are typically unable to attend school. This is due to barriers related to lack of information, unsafe passage to school, weak prior learning and/or the lack of sibling care in schools. Now in 2024, we hold a diverse mix of education and community interventions. The Bridge Program now has three versions. We are also intervening in Grades 1-2-3 of Nali Kali classrooms in nine schools. Nali Kali is a multi-grade and multi-level (MGML), activity-based teaching-learning program for Grades 1-2-3, which is being implemented in government schools in Karnataka.

We have a community vertical that works across 30 communities. It helps migrants access welfare benefits and documentation. We also operate a health initiative that runs a free Primary Health Centre in Kariyammana Agrahara (KA).

This growth, both in scale and complexity, has not been due to any well laid out plans. This has been a result of our responses to systemic issues and to a rapidly shifting context. At the same time, we have been keeping an eye on our cause and philosophy of creating meaning for the marginalized children and their families.

In the next part of the article, I provide details of two pivotal experiences we have had in the space of education in these years. These have taught us to listen to the wisdom from the ground and challenge our own assumptions without ego. They have guided us to design programs that have worked.

The Kodathi GHPS experience

Bridge to Grades 1-2-3: The first challenge to our model came within six months of starting. When our first batch of 15 children from the bridge program was ready to be mainstreamed into their primary grades, we realized that the school was facing a serious teacher crunch.

It was barely functioning with 140 children and two teachers. Teacher appointments had been stalled. The peri-urban location of the school with no HRA (House Rent Allowance) meant that it wasn’t an attractive posting for teachers.

Our Bridge Program would have been toothless if we didn’t address the issue of dysfunctional classes in Grades 1-2-3, where the children were to be mainstreamed. We had to plan overnight to fully enter the Nali Kali space to make things work. We had to learn its MGML methodology from scratch.

Our team of two teachers and co-founders headed to Yadgir to be trained in the method by the Azim Premji Foundation (APF) team. We also attended a workshop organized by Rishi Valley on global experiences with multi-level classrooms. In hindsight, these decisions were made in quick succession and a continuous process of adapting to a new normal.

Expanding the idea of bridging: The plot started thickening. We had in our Bridge Program adolescents from out of the State (12 years and above), whose context seemed painfully complicated. They were too old to catch up to an academic Kannada syllabus in the school. They and us were staring at a fast-closing window to school completion.

Having older children in the same community, not schooled, would have a negative effect on younger children. On the other hand, older children who complete schooling would be powerful role models. This was an idea we could not ignore.

We spun off a small engagement with one student within our Bridge program. Three more were added subsequently. We tried taking them toward Grade 10 of NIOS (National Institute of Open Schooling), resourced entirely with volunteer teachers.

Open schooling gave us the flexibility to work on FNL (Foundational Numeracy and Literacy) and stagger subjects. It also provided the freedom to move at a pace best suited to this older student who had lost ground. This was an option not available in a regular government school.

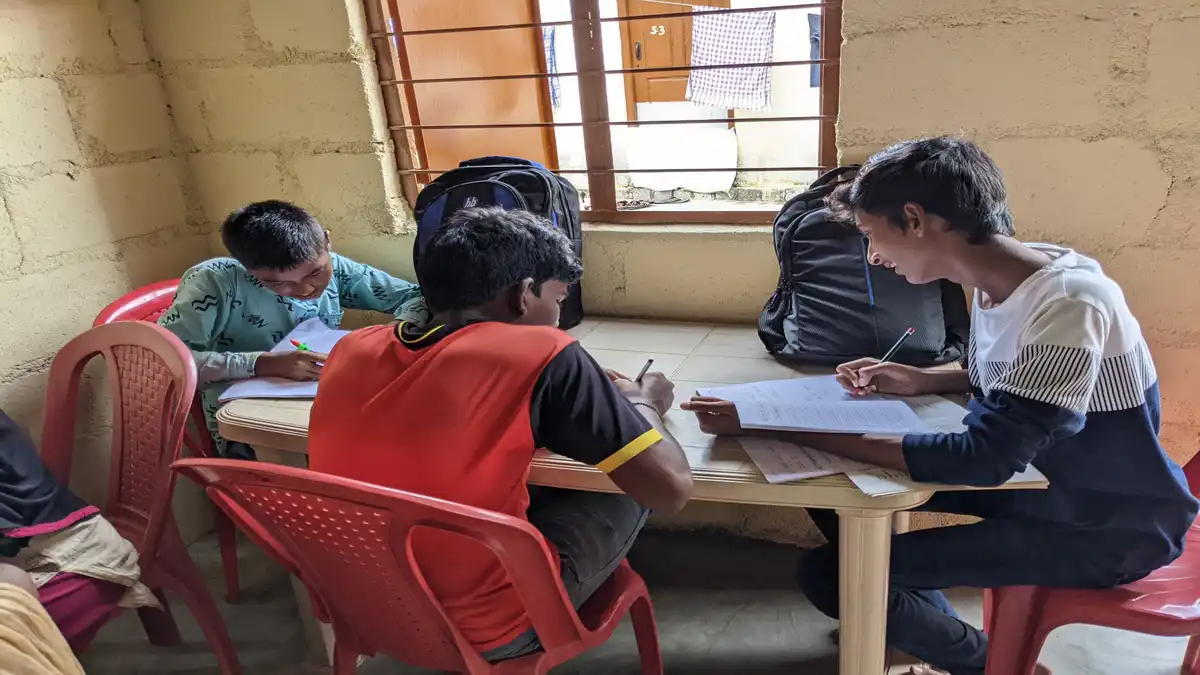

Today, we have a well-defined program for Grade 10 NIOS. We have around 30 students in various stages of Grade 10 completion. This program is operational across two locations. There is an option with Kannada as the medium of instruction as well. The children in the program are supported by five teachers. Our first batch of three students are undergraduates in Azim Premji University. That’s life turning a full circle for us!

After the COVID-19 pandemic, we added another element to the Kodathi Bridge program. This tried to integrate older, in-state migrant students (aged 9-13 years) into their grades after a year of fast tracking.

From a monolithic idea of a bridge program, we branched into alternate forms of bridging. There is an NIOS option for the older students. We are also intervening in the Nali Kalli program in Grades 1-2-3. We have had to evolve to suit the context of our students.

Now onto the second key experience. “But that’s the trouble with me. I give myself very good advice, but very seldom follow it.” – Alice in Wonderland

Our experience of the community learning centre in Kariyammana Agrahara

We had to challenge our original assumption of working inside a government school again in 2022 as the aftereffects of the COVID-19 pandemic started hitting us on the ground. In-migration into the city, particularly from Assam and West Bengal, had exploded. There were many more children who were out of school than we had imagined.

In response, we started a full-fledged Community Learning Centre (CLC) (located close to the settlement) in Kariyammana Agrahara (KA) in April 2022. The Bridge Program is now in its third year of operation with 170 children (3-18 years). How did our context lead us there?

Force majeure and the best laid plans: Before the pandemic, we used to bus 25 children belonging to North Karnataka and bordering Andhra, to our second Bridge location in Sulikunte Dinne (6 kms) from Kariyammana Agrahara (KA). KA is a dense migrant settlement of around 3,500 households. They are packed in a radius of two kilometers off the Outer Ring Road, Bengaluru’s IT hub.

These families supply the support staff to the tech industry. Their members work as housekeeping staff in tech parks. They also work as security guards and helpers in upscale apartment blocks in the neighborhood. In a sharp contrast with the spaces they work in, they live in abject conditions.

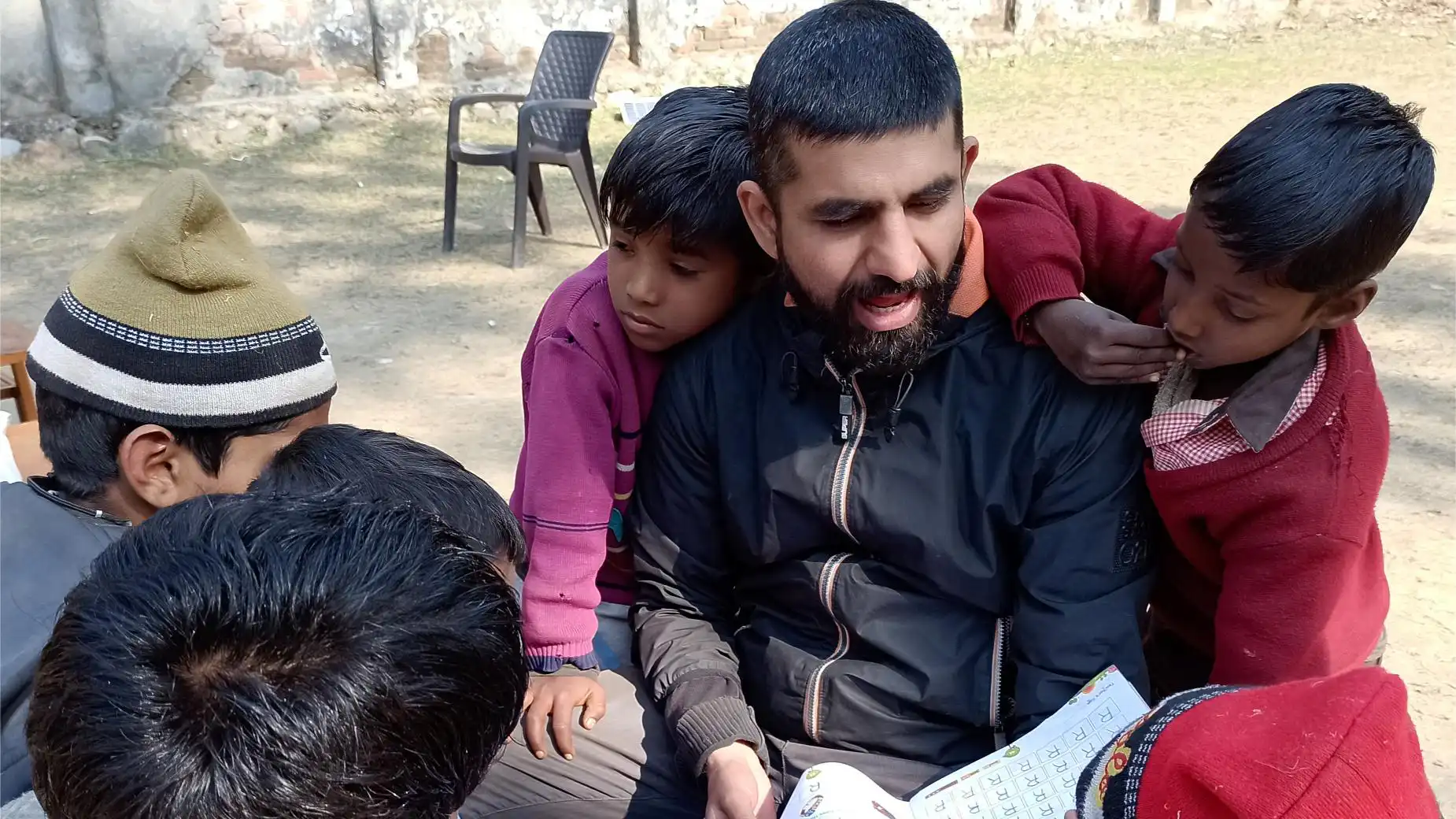

As schools had closed, our Sulikunte Bridge team of teachers (like teachers in all other programs) taught students near their settlements (in this case in a temple yard). As we became more visible to the communities, our enrolments shot up from 25 to 75 and then to 100+ in under a year.

The watershed moment came in October 2021, when our community vertical started a Primary Health Clinic (in partnership with the Foundation) in the area. This opened the floodgates for communities that we had hitherto not reached – displaced families from Assam and West Bengal. They had no viable schooling options. Local government schools (which in any case were closed) had cultural and linguistic barriers. Low fee paying (LFP) schools were unaffordable.

Dizzying pivots: We had nothing in our tool kit to solve for this deluge. Our curriculum was Kannada-focused. Our teachers were Kannada competent. Maybe they had a smattering of Hindi skills. We had no prior experience working with these communities. We had to understand their socio-cultural contexts first.

These families saw meaning in English as a language of schooling. They saw it as a more portable language that would stay relevant wherever they went, whereas knowing only Kannada would restrict their choices.

From October 2021 to April 2022 – within a short span of one and half years – we had the current KA Community Learning Centre up and running. Again WIPRO backed us to take the risks. This center became operational in ten rental rooms. It was in close proximity to the settlement.

Enrollments since then have never dipped below 130 in the Bridge Program, and 40 in the Early Childhood Program. We see the latter as a necessary adjunct to our Bridge Program. Our waiting lists are always brimming. We painfully turn back fresh enquiries for admissions as we have capacity constraints.

Our curriculum in this program has pivoted completely to an English medium, open schooling structure. We work on open schooling of Grade 10 here. We also work on Grades 3, 5 and 8 (called the Open Basic Education – OBE) with younger children. Thirty children successfully got their NIOS exam certification earlier this year. Many others will do so next year. The program does not seek to be informal. It gives the legitimacy of exam certification. Our teacher profile now is of primarily English competent graduates or postgraduates from Azim Premji University and other institutions.

In conclusion

All our work in education still has one single aim of including marginalized children into mainstream education. However, versions of the Bridge Program different from our original conception were born squarely out of an unfulfilled need on the ground. Our interventions in the Nali Kali Program came out of a systemic context of teacher shortage.

Our KA Community Learning Centre experience has made us understood something crucial. To fix our locus inside the physical space of a government school alone would mean that we would ignore the larger problem of the ‘out of school’ child. This issue exists outside of school spaces – in the settlements themselves.

No matter how many bridge programs we open inside a school – there will always be children who will hesitate to enter such formal spaces. These children may be adolescents, unschooled children, and children still too steeped in the rural context, and so on.

Community centers are powerful ways to reach the last child. The effectiveness of this approach has been demonstrated through the pioneering work of other experienced organizations like Muskan in Bhopal and Sakthi Vidiyal (after school programs) in Madurai.

What we have learnt from these two experiences is this – learn and adapt. Shape shift, if you have to. Always respond to the context.

Where next?

Our Nali Kali program will continue to strengthen FLN from inside the system, for as long as the system needs us. We know that the system, the Education Department, policy makers (all the top-down actors) are not fully ready to accommodate the idea of a bridge space outside the physical and legal construct of a school, or for that matter a Bridge Program existing in tandem, inside the school. But it still does not take away from the need for it and its power to shift the ground for countless forgotten children.

As we speak, we are in consultation with the Education Department to give space – physical and ideological – to children who are unable to enter and thrive in a conventional classroom. We are advocating for Bridge Programs – with OBE, NIOS certification options – to be part of public schools. The coming months will be crucial in setting the direction for this process.

Making an intervention relevant to a community could mean razing all pre-held notions to the ground. This would entail simply aligning to the context. It may be emotionally painful. However, our experiences have taught us that such pain is always worth it.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!