Writing histories for children: the case of the Partition of India

This article focuses on an illustrated Bangla book on Partition, which the author wrote for middle school children (aged 12+). In the piece she reflects on the rationale of writing the book, a few ethical and methodological concerns, and the book’s reception among a group of underprivileged children. Their engagements with the book provide a cue for pedagogical experiments in teaching history at the school level.

The memories of partition refuse to die down in the Indian Subcontinent. They resurface in various avatars—as bitter-sweet nostalgia for the abandoned land and people, as artefacts and oral histories carefully curated in various museums, and as justifications for majoritarian violence in varied forms. The chapters on partition in most history textbooks are too drab and heavy with information to deal with the range of emotions that the event invokes.

Consequently, it is a potent site for the circulation of misinformation, distorted narratives, linear accounts of the past with clearly defined heroes and villains, and for religious identity formation. Of course, it is also a site that has the potential to challenge statist ways of commemorating partition. This is also a space that can accommodate memories of inter-religious friendships and solidarities, and voices and efforts to resist communalism.

Making sense of partition: the story of ‘Deshbhag’

In this context, I wrote a Bangla book on partition keeping in mind the middle school children (aged 12+). Written and published in 2022, the book titled ‘Itihashe hatekhori: deshbhag’ (‘First history lessons: partition’), was the first one of a nine-book series published over three years (2022-2024). The series is an outcome of a project named ‘Revisiting the craft of history-writing for children,’ funded by the Rosa Luxembourg Stiftung South Asia, and housed at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK). The series was edited by Debarati Bagchi and me. In this short article, I primarily focus on the book ‘Deshbhag’/ ‘Partition.’ However, I situate the book within the institutions, and the entire series is important for any critical reading of it.

When I wrote ‘Deshbhag’ I had four primary objectives. The first one was to highlight that there was no one experience of partition, no single hero or villain, no single perpetrator of violence or one victim. The second was to provide a sense of historiography of partition studies. Another related objective was to indicate the importance of sources in the writing historical narratives. Given the audience, a very central objective was to make the text lucid and fun and the book attractive for the young readers. A brief description of the book and a summary of the content will elaborate the narrative strategies and techniques I adopted to meet these objectives.

Understanding partition: the why, how, and the what

Around 6,000 words long, the book has six chapters. These address three questions. First, why did partition happen? Second, how did partition happen? And third, what were its consequences for the ordinary people of that time? As anyone aware of the partition scholarship will know, these are some of the key questions for the academics as well. Whether partition was the consequence of Congress politics or that of the League’s, or the British had the key role to play—these questions have been fiercely debated by the historians.

Chapter one, without naming the historians, flesh out the main contours of that debate. The next two chapters focus on the implementation of partition on the ground by focusing on the making of the Indo-Pakistan boundary and the division of imperial territories of British India between the two new nation-states. Written in an anecdotal style, the idea was to elaborate how partition shaped the making of India and Pakistan in a very tangible, material way.

The larger ideological point was to convey that nation-states are not given, eternal entities. They are produced ideologically and infrastructurally. They often change their shapes and forms at different historical junctures. This, I hope, will help the young readers to look at ‘secessionist movements’ critically, moving beyond the binary of national-antinational.

The last three chapters focused on the diverse experiences of partition: what did it mean in different parts of the country (Punjab, Bengal, Assam, and the Andamans). How did it affect the women, the Dalits, and the Muslims of India? These chapters focus on narratives of suffering as well as of grit and resilience. The three chapters taken together also highlight how the unfolding of partition was a long-drawn process, affecting various people at various points of time and shaping their lives permanently.

To strongly communicate that history must be based on ‘verifiable sources’, ‘Itihashe hatekhori: Deshbhag’ (and all the other books of the series) has a brief section on sources and a list of further reading. The goal is to indicate the necessary rigor that all historical writing should have. This section also tries to demonstrate that I did not make up the ‘stories’ that are told in the book.

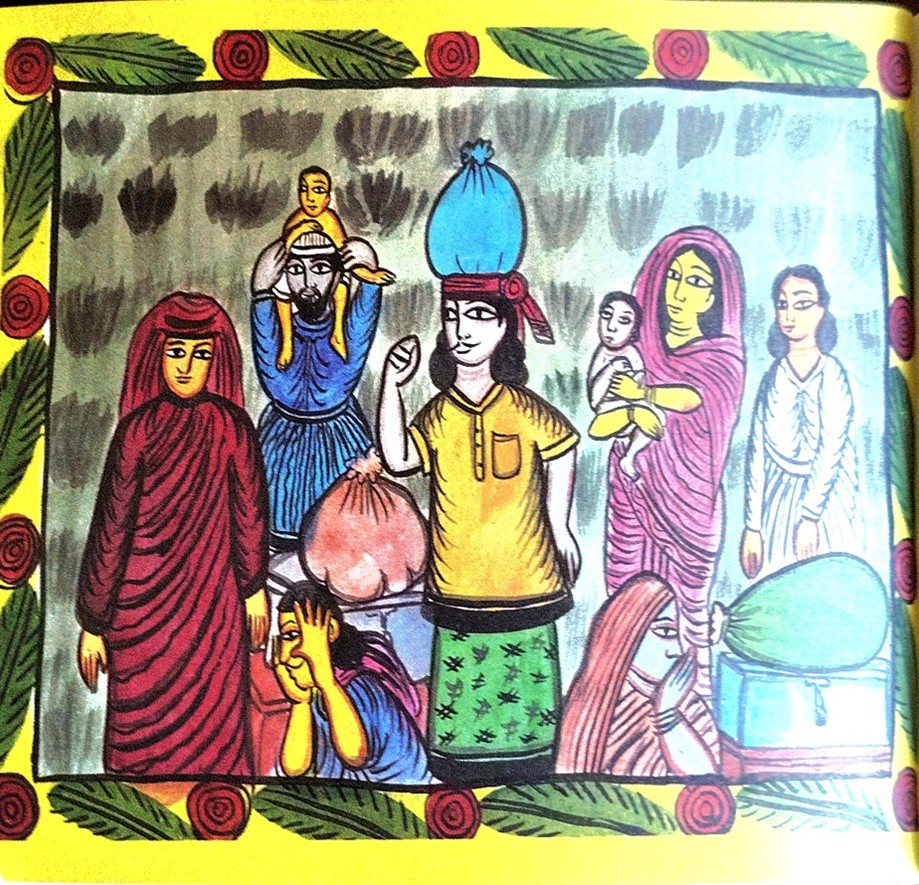

The first edition of the book also had sixteen coloured illustrations done by two scroll painters from rural Bengal (patachitra artists/Patuas), Ranjit Chitrakar and his son, Siraj Chitrakar. The dimension of the book, the illustrations, its focus on a single issue (i.e., partition), the section on sources, use of anecdotes to convey the larger points, the language itself—set it apart from the textbooks.

The book at work: engaging with narratives of migration to understand partition

We did multiple interactive sessions around the book with middle school children. The children we worked with (for this book) mostly belong to families of migrant workers. They go to regular government schools. They also receive free educational assistance from different community schools of the city. We approached them through these community schools.

After each reading session, the children were asked to draw or write about themes that they found interesting and could relate to. We noticed that a recurrent theme in many illustrations was rural-urban and urban-rural migration. Many of these students who attended the workshops and lived in urban slums have personal experiences of migration. Their families had migrated to Kolkata from rural West Bengal in search of work. Some of them have extended families and friends in their ancestral villages who they occasionally visit.

Therefore, leaving one place and settling down elsewhere—be it because of partition or due to poverty—is something these children were familiar with. Drawing migration was an obvious choice for many of them. The pictures of migration that they drew were often very detailed. They drew themselves and their family members, the transport they took to or from Kolkata. They sometimes included the names of their villages as well. Shared below is an example of such a drawing.

The illustration shared above shows a train, a railway station named Joynagar and two people with luggage. Joynagar, a small town in the district of South 24 Parganas in the state of West Bengal, is the nearest railway station to Mohon’s (name changed) village. Several daily trains connect Joynagar to Kolkata. By drawing the specific station and the train, he has documented his journey, his family’s journey and many journeys like theirs.

I did not necessarily anticipate that the children would draw their own journeys from their villages to Kolkata, or the other way around. However, once they did so, the connections with the ‘Deshbhag’ book were quite apparent. Similar pictures were drawn by Asmara (name changed) of Class VI, whose parents have come to Kolkata from Malda for work. The same was the case with Sonali (name changed) who, along with her mother, visits her grandparents back in her ancestral village in South 24 Parganas.

Should we make sense of the past through the present?

Such illustrations and conversations with the children taught us something important. Children often make sense of the past through their lived experience. Partition, the making of India and Pakistan and consequent refugee migration were new information to most of them. But those who had remembered their own migration from village to city made sense of the books through their own experiences.

As someone trained in history, I am not sure what I feel about this tendency. My discomfort comes from the fact that making sense of the past through present may give the impression of linearity between the past and the present. This may read anachronistic at times.

In conclusion

The contemporary and the past are connected in non-linear ways. Connections are constructed by various stakeholders in different ways. Looking for linear connections may make us look at the past through the binary lens of similarity and dissimilarity. However, this approach perhaps contends a pedagogic possibility as this may make the students curious about the past. The past becomes relatable to them.

Often, I am told students find history irrelevant and boring. Making the discipline exciting is the necessary first step toward developing historical consciousness among the young minds. If that is true, is a slight compromise with the grammar of the discipline the way forward? I keep this question open for us and for teachers, parents, education activists, and other stakeholders.

Endnotes

- This article, however, is written in my individual capacity and does not necessarily convey the opinion of my co-editor or other writers of the series.

- These are not regular schools affiliated to any government board. The children who attend these schools are also enrolled in local government schools. However, unlike conventional private tutorial system, students do not generally pay to attend these schools. Thus, they cater to children who cannot afford private tuition in a country where “private tuition at the primary stage has become as necessary a chapter as going to school.” (Manabi Majumdar, ‘The shadow school system and new class divisions in India’ (TRG Poverty and Education Working Paper 2 – London: German Historical Institute London, 2014) The other difference between a conventional tuition and a community school is that the latter is usually an ideologically driven initiative.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!