Going beyond the narrative: a hands-on approach to introducing the historical method to middle graders

While narrative is a key component of history pedagogy at the school level, the capacity to make the connection between the narrative and historical thinking skills is equally important. Without this, the subject will be devoid of the rigour of the discipline that it seeks to teach.

Photo credit: commons.wikimedia.org/Saiphani02

Ever since the inception of history as a subject in the school curriculum, narrative history has been central to its classroom teaching. This seems logical. Storytelling as a device to make sense of human existence is an ancient practice.

In its modern avatar, history in school textbooks strives to create a sense of engagement of young people with their past, connecting them to their heritage and traditions. The subject generally appears as a sequence of events, highlighting important figures and dates, emphasizing a shared past and a common understanding of the student’s group identity in the world. This received narrative is most often told in an omniscient voice, seeking to present a broad, unitary story.

It is a linear presentation, that, at its simplest, asks nothing more of the student than an ability to regurgitate events, dates and figures for an examination. Hence, the oft repeated complaint of history as ‘boring’ or even ‘irrelevant.’

Undoubtedly, the narrative is a great tool for instruction in history education. Learning cause and effect, chronology and a global perspective of events are important competencies for middle grade and high school history students.

However, narrative building is only one aspect of the discipline of history. The all-knowing voice of the school textbook that seeks to present itself as the historical truth, is, in fact, only one interpretation of what happened in the past, shaped by the selection of historians with their own values and ideologies.

E H Carr, in his seminal work, ‘What is History?’ describes the creation of history as a reciprocity between past and present, in which the idea of an objective historical fact independent of the historian’s interpretation is a “preposterous fallacy.” “History is interpretation,” he famously stated.

In other words, while narrative is a key component of the pedagogy, understanding how and by whom narratives are made is equally crucial. Otherwise, the subject will be devoid of the rigor of the discipline that it seeks to teach.

The purely narrative approach ignores the historical method. The historian’s craft is a complex interplay of reading and interpreting sources such as material remains, texts, inscriptions, archival records and oral sources. These are subjected to critical evaluation and processing, comparisons and connection making. The process is subject to periodic reviews, the questions asked of sources often changing with new evidence and links to contemporary issues.

The risks of not understanding the historical method are manifold. A narrative can be biased, shaped by power, ideology or lack of cultural context. The student who reads uncritically is vulnerable to being manipulated or controlled by simplified or distorted views of the past, mythologizing, or propaganda. Accepting a dominant monolithic story usually means reading a history devoid of nuance or the diversity of the human experience, often ignoring the voices of the marginalized.

Today, it is hard to imagine Indian history without the stories of peasants, tribal communities, and the working class. Most of these were restored with the ‘history from below’ approach of the Subaltern Studies Group in the 1980s that changed the elite-focused narratives. Or the Dalit writing that challenged caste hierarchies in the wake of B R Ambedkar’s writings. Or those of women who combined the fight for freedom from colonial rule with calls for social reform in the gender space. These voices emerged from questioning the prevailing historical narrative.

In this regard, The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) history textbook series, Themes in World History and Themes in Indian History, do present the importance of historiography to Grade XI and XII students respectively. These textbooks highlight the craft of the historian and examine it through theme-based studies.

However, given that History is an elective subject in Grades XI and XII in most Indian examination systems, it is important that the capacity to make the connections between the narrative and historical thinking skills be introduced much earlier.

For history teachers, already racing through the term to cover a vast curriculum, the idea of introducing the historical method into the mix might seem a daunting task. One way to overcome this is to introduce a few simple classroom activities to increase a sense of engagement with the subject. For example, evaluating everyday modern objects like clothing, tools or sports equipment and what they reveal about our times from the perspective of people in the future.

Other techniques could include analyzing how a current event will be remembered by history through textual records or discussing how perspectives on certain well-known events of the past have changed with the introduction of newer voices. Interviewing someone who may have been through a significant event in history can spark discussions on lived history.

There are currently plenty of online resources with digitized primary documents like photographs and artefacts which can be accessed to examine the differences between primary and secondary sources. Visits to monuments can bring important perspective when students are required to critically analyze the source through discussions on the original purpose of the building, the intended audience and its changing meaning over time. If curricular reading material falls short in addressing the historical method, supplementary works could fill the gap.

Through my works of narrative non-fiction for young readers, I have attempted to highlight a range of primary sources that have built narratives of Indian history. ‘India through archaeology: excavating history’ uses a visually appealing approach that might pique the interest of middle graders. The book shows the interconnectedness of ideas, events and influences in Indian history though the discovery and analysis of material remains such as megaliths, coins, pillar and rock edicts, copper plate inscriptions, hero stones and cave paintings.

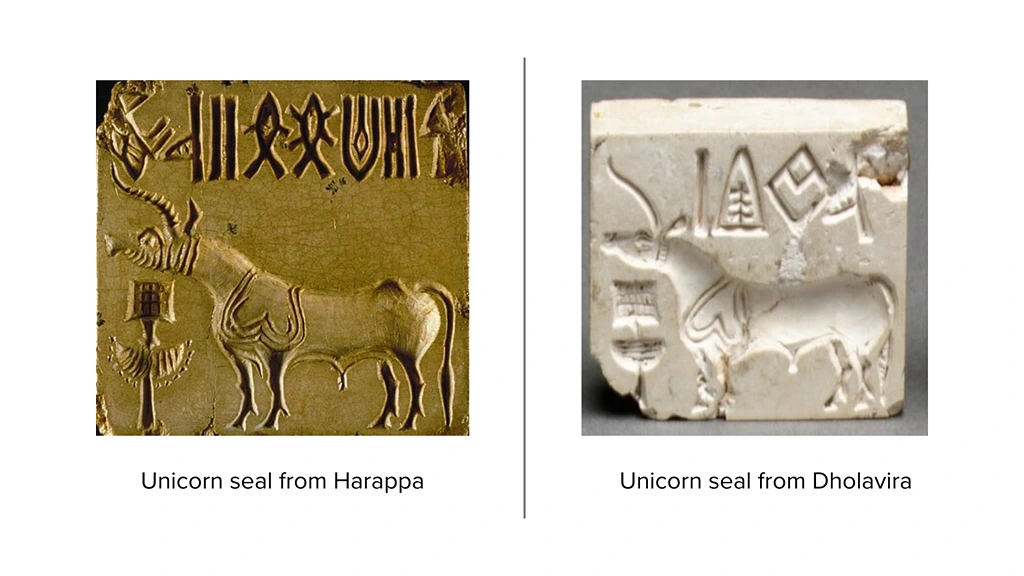

Presenting the book to middle grade school students, I often work in ‘reverse.’ We enquire about the stories in their textbooks and then examine how those stories were constructed. Choosing a relatively well-known period where students are familiar with the narrative such as the Harappan civilization, I would then discuss, using prompts from the book, the excavations, artefacts and other material sources that built that story.

Similarly, in ‘A children’s history of India in 100 objects,’ objects covering a range from prehistory to contemporary times are individually analyzed. These are examined for the information they provide to the historian and how that contributes to stories of identity building. Prehistoric stone tools, weaponry, decorative art, religious icons and a host of other material sources have been chosen to reflect, as far as possible, the diverse cultures of the subcontinent. School discussions on the book often focus on the varied voices that speak from primary sources and their influence on history writing. Examples of these include hero stones of the early medieval period, which reflect the lives of ordinary people who may not otherwise be mentioned in historical records.

Understanding how historical narratives are written enables young people to do history rather than just learn history. In addition to enhancing critical thinking skills, it makes them more discerning of historical claims. They begin to read history with a questioning of the information presented to them, an awareness of varied perspectives of the same event, of missing voices in the narrative or of the impact of these events on their own lives. These are insights that persuade them of the relevance of history and how it shapes the present. This approach eventually makes engaged and empathetic citizens, able to take more informed decisions for the future.

References

Carr, E. H. What Is History? London: Penguin Modern Classics, 2018.

Cariapa, Devika. India through archaeology: excavating history. Chennai: Tulika Publishers, 2017.

Cariapa, Devika. A children’s history of India in 100 objects. Gurugram: Penguin Random House India, 2023.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!