Careful with writing History and wise with teaching it in schools

The past is another place and recounting it shall always involve some choice or bias. But no History can be written without proper chronology and credible evidence. School textbooks on History need to pay attention to all this.

History is the narration of human endeavors in the past. This narration is consciously based on intelligible written evidence and/or it may be derived from artifacts found at archaeological sites. Slowly, personal choice from available evidence to build a narrative is being accepted by scholars. But professional historians would still define their narrative to be real, truthful, and objective.

A schoolteacher could turn around and ask, “So what? School students live in the present. They are being prepared for becoming good citizens tomorrow. Why burden the school goers with narratives of the past, especially when historians quarrel among themselves over stories?”

The past and present of teaching History

In his book, ‘The school and society’ (1915), John Dewey (1859-1952) wrote an article titled ‘The aim of history in elementary education.’ History is indirect Sociology, said Dewey. The present is very complex for children, and they are too close to it to make sense of institutions and processes. By speaking about the changes and continuities of social institutions, History simplifies the understanding of the present for learners. From hunting gathering to settled agriculture and from industry to the ‘office-centric’ present in cities, History helps school goers understand chronology and progress.

Mass education began in the late 18th century and History began to be taught in schools thereafter. The organization of mass education systems is around two centuries old. Globally, at the time when unwieldy empires gave way to modern nation states in the 19th century, the process for mass education was accelerated by urbanization and industrialization.

The purpose of this mass education is ‘human flourishing’ and citizenship formation. The goal of ‘human flourishing’ broadly means that education attempts to prepare learners for a full life. It goes beyond making them skilled workers or curriculum crammers. To ensure the well-being of a learner, education has to be holistic and wholesome. It must also impart values and help build character.

After the start of mass education, the stages of school education were defined as Primary, Middle, and Secondary. As a subject, History got a prominent place in the syllabus of the Middle school and the higher grades. Our focus here is why, when and how History has been taught in schools.

From political to social history

Earlier, all History textbooks were like a catalog of sovereigns, their empires and their wars and occasional acts for the benefit of their subjects. One dynasty followed another, the religion of the ruler defined a period, and the piety of the ruler was pitted against her/his intolerance.

Much ink was spilt over such narratives when scholars asked, “What lesson do we hope to teach students by recalling the bigotry of rulers? Why did we expect the 13th century Turks to be secular when the concept is new and still evolving?” Searching for anachronisms is not good history and why recount tyrannies of the past, which inspires no one, these scholars argue.

History can be of many kinds. Scholars had moved away from the political history of rulers in the last century. They were writing about society and economy in the past ages. Feudalism and capitalism, urbanization and industrialization were discussed. Colonies were conquered by the new industrial nations of the West. What the rising West did to the languishing rest also became a matter of interest.

From scholarly books, the making of feudalism and capitalism as also colonialism were picked up for the curriculum of schools. Interesting chapters in history textbooks recalled the life of hunters and gatherers, the paternalistic act of Ashoka of prescribing socio-moral duty to his subjects by rock edicts, the making of roads, inns and ponds by beneficent rulers, the clothes different classes of men and women wore, the pauperization of the colonies at the time of the enrichment of the West, the game of cricket and the role of caste in it, etc. Practically, no subject was taboo. School textbooks of History discussed the everyday life of ordinary people in novel ways.

In our country, often attempts are made to yoke History textbooks in government-controlled Boards to the prevailing political winds. Eulogizing the past can bring some misplaced catharsis. However, it does not enhance our understanding of History. Chest-thumping about being ‘the first and the best’ is good theatre. But nurturing chauvinism cannot be the goal of good education in any society.

Make a choice, wisely

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter,” proclaimed Chinua Achebe. This rhetorical statement is one-sided but popular among all, except professional historians.

A realization has dawned on historians that scientific objective History without a bias may be impossible. Hence, we rather prefer the idea of Benedetto Croce (1866-1952), viz., “All history in contemporary History.” By this Croce means that the present-day concerns and perspectives of historians cast a shadow on their work.

But a history book must be the opposite of feature films, and the author should underline this fact by making such a statement. Films declare that “any resemblance with reality is coincidental.” In reverse, History books should declare that any resemblance with fiction is coincidental because the author wanted to stick to facts, evidence and truth, etc.

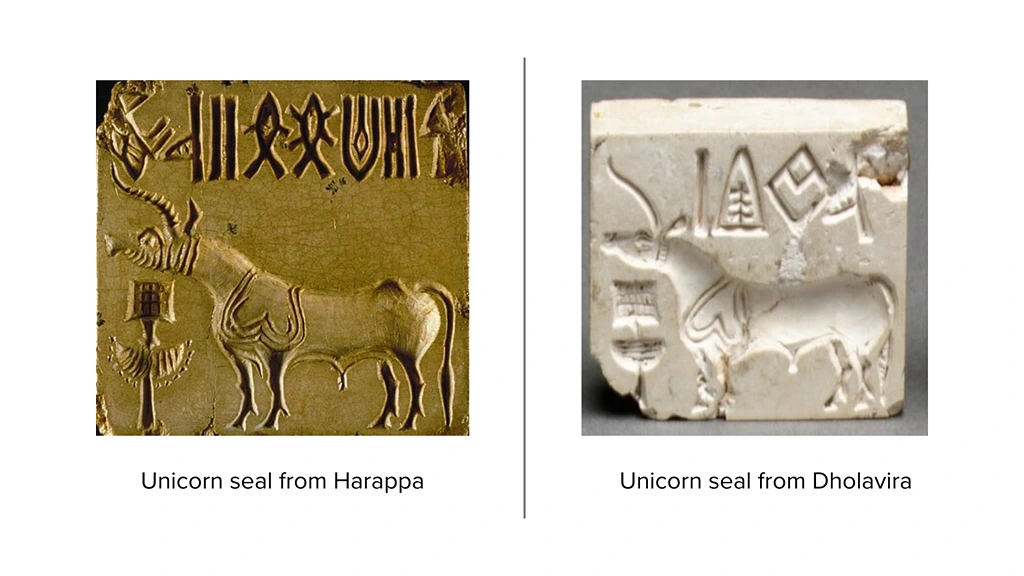

So, history can’t be based on the undeciphered script of Indus Valley civilization. And not all stones strewn across the site of a civilization can be historical. Instead, a rock inscription in an intelligible script and a tool made out of stone can be called a source of history. Evidence matters in both scholarly books of History and school textbooks.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!