In search of historical time

This article discusses the concept of historical time and shows why grappling with it is important for pedagogic processes related to the teaching and learning of History in school classrooms.

History is often understood today as the study of past human activities and their consequences on humanity and the world. Historical time, by this understanding, is constrained from the time of the origins of the human species till yesterday, and the evidence of the impact their activities have left on the planet. For example, the age of Ashoka, as we studied in school history, is defined by the fragments of evidence left from his time—coins, inscriptions, pillars and ruins from within a particular geographical boundary that ranged from many parts of northern and eastern India, extending far south into the peninsula.

The dates and events in the textbooks are often much dreaded or groaned at by students. One possible reason is that we do not attempt to present an experience of the past. Mostly we share information and dates, which are otherwise intangible and often consist of only numbers.

A pattern on a piece of cloth emerges from embroidering threads of different colors, which all come together to form the design. Similarly, when the past’s tangible remnants are used to weave a narrative, the evidence must link up, like the stitches on textile, otherwise narrative patterns will not emerge. This narrative is then located in time by our understanding of historical time. And when the narrative and time come together, you have a good story to tell and there is likely to be fewer groans in the history class.

The boundaries of historical time

The boundaries of historical time are open to question. For instance, does the stone age come in historical time? In the stone age, the remains of the past are often single pieces of flint, rarely extending to something sizeable as clusters of dolmens in different parts of the world. So, we are left with glimpses of narratives from many places, which we then weave together as a global phenomenon. Is the stone age in Raichur in South India the same as stone age in Europe or Africa?

This is where definitions and a framework to understand time are useful. The stone age is typically classified as ‘pre-historic,’ indicating a time before the evolution of writing systems. A writing system is a collection of symbols that are used in combinations to form meaningful symbolic groups (such as words) used with predictable rules (grammar) to describe the surroundings or capture action. What is the significance of writing systems in this context?

Writing is a direct record of the thoughts that were in the minds of the people who put down those scribbles or notes on stone inscriptions, clay tablets, metal coins or vessels or paper scrolls. Writing allows documentation of events and communicates intentions. It also records declarations of boundaries, prayers of hope and treaties of peace. Writing gives glimpses into the lives of people as they wished them to be recorded at the time as well. Considering this approach typically restricts historical time, as including events after the appearance of written records, roughly 5,000 years before the present.

Even then, the question of measuring historical time is neither simple nor straightforward. There is no physical clock today that can be turned back to take us back in time. You need to know a sure way of saying that objects or monuments that are being used to define the past are from that time in the past. You also need to find a way to say objects or events from different places may date from a similar timeframe.

How do we know that something is old?

There are ways in which we can say an event happened in the past.

You need to define a useful measure of time—seconds, minutes, hours, years and other similar units in different cultures. A measure of time that is based on the time taken to walk between two points is not useful in this context. These units need to be defined separately and uniquely.

You can measure a definite unit of time—if you find a piece of charred wood in a cave, you can measure the time when the wood was first formed as part of a tree. You can do this using the radioactivity in carbon atoms in the wood, and this gives you a reasonably precise date going back ‘x’ number of years from the present. You can do the same with paper, maps—any material that contains carbon. Similar methods can be used for radioactivity in oxygen atoms found in calcium carbonate found in shells and fish bones.

There are also milestones that are useful. We can use an acknowledged event in the past as a marker or milestone and measure everything that happened as before or after that event. The concept of B.C. and A.D. is rooted in this type of idea, as before or after the year of the birth of Christ. There exist several timelines in different parts of the world that were developed using other milestones.

Records of events or people exist—in cases where events or people are recorded in coins, stone or metal inscriptions, and manuscripts, the details in these records allow for comparison across different sources, where available. These also allow for an opportunity to weigh them as evidence of historical events or people or pronouncements.

In addition to these measurement units, evidence from archaeological sites is often useful in measuring historical time. In such circumstances, we can think of the following additional points.

Evidence from archaeological sites

Historical objects can look old. A metal coin from a much older era found in an archaeological site looks different from the ones in use today. It often looks rubbed, dented and sometimes broken. We often assume these marks to have been because of time and events. Similarly, a broken wall that has a tree growing out of it can be assumed to be older than a freshy painted wall, unless the latter has been renovated and upgraded!

Older layers are below younger ones. In any archeological dig site (ruins, old structures), unless there is a good reason to find signs or reasons for disturbance, layers closer to the surface are younger than layers further below. Objects found in lower layers are likely to be older than objects in upper layers unless they were buried deep. The coin mentioned in a previous point was found buried in a field. The coin was found alongside other coins, broken pottery, and other artefacts. There were other shards of pottery found further below. These were found in a separate layer, which are likely to be older than the coin.

Continuity across physical space is also an important point to keep in mind. Layers of one archeological site can be compared to layers in another if the layers have a similar composition of objects or artefacts.

The age of Dholavira: an example

Using a combination of the ideas shared in the two preceding sections, you can say, for instance, that the city of Dholavira in today’s Gujarat existed between 2650 BC and 1450 BC. How do we know these dates?

We have found pottery and artefacts which are like the ones found in other locations such as Harappa, linking Dholavira with other cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Radiocarbon dating of seashells found in Dholavira helped us date these to be in the range of 2600 BC to 1400 BC.

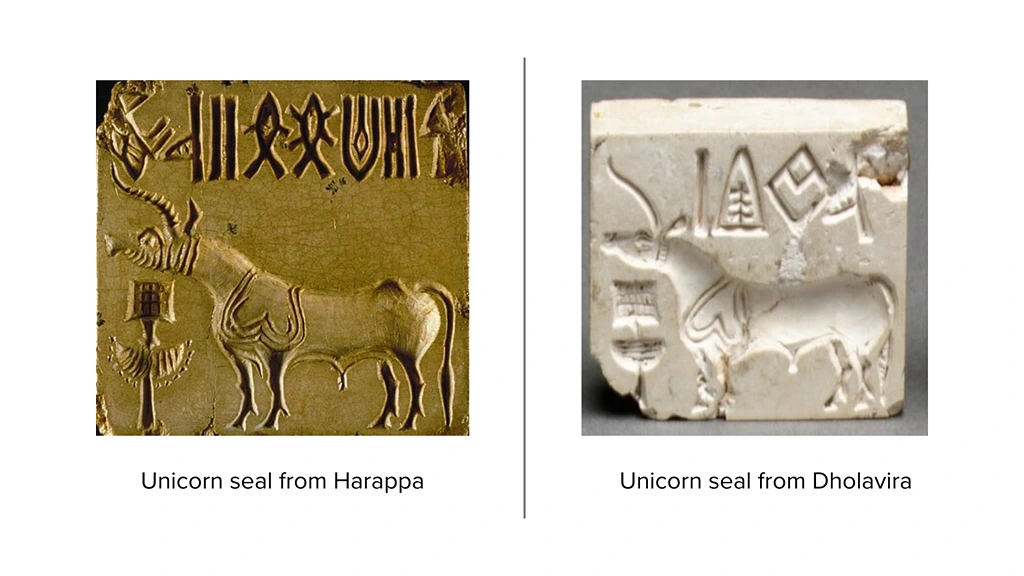

We have discovered objects in different layers in Dholavira that correspond to similar objects found in similar layers in Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa and other Indus Valley sites. An example of a unicorn seal from Harappa in Pakistan, which is 1,400 kilometers away from Dholavira in Gujarat, where a similar unicorn seal was found is shown here. The written symbols on the seals are yet to be undeciphered. However, the resemblance of the two figures is striking. This links a source with shared cultural and seal-making roots across a wide geography at that time.

In other cases of river civilizations contemporaneous to the Indus Valley, as in Egypt and Iraq, the writing systems have been deciphered giving us a significant insight into the social and cultural lives of the people living in those regions at the time. The structural ruins of the Indus Valley civilizations do tell a story of a complex civilization in historical time. But our lack of ability to decipher the script sometimes restricts our attempts to interpret the structures and symbolic features.

Time in oral history

Oral History poses an interesting challenge for historical time since it is based on the living memory of people who had experienced an event in the past. The difficulty here is to accurately describe the details of an event, the people and actions involved for instance, based on eyewitness accounts alone. Memories are fallible and individual interpretations of an eyewitness can be subjective.

The approach in such cases is to use contemporary accounts or objects that may have survived the time and attempt to link them with eyewitness statements which may be recorded later in time. The accounts of people who had previously lived under different repressive governments across the world or the memories of past tsunamis in the oral traditions of coastal tribal communities in the Nicobar Islands and elsewhere are among the range of examples that can be explored to understand the experience of historical time in witnesses of events.

In conclusion

Historical time, thus, is an important concept to understand how the methodology of history works. It is central to how narratives in historical texts are constructed and understood. It is also a critical part of how evidence is gathered and used to construct arguments in the subject of History.

Having insights into historical time can help all of us—educators, students, and those who work with teachers—better grapple with questions related to the geographical spread of socio-political and cultural phenomenon in specific period of time. Therefore, having a basic idea about this concept can help learners engage with the subject of History in classrooms in a meaningful fashion.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!