Promoting inclusion in ECCE: challenges, strategies and pathways to develop inclusive classrooms

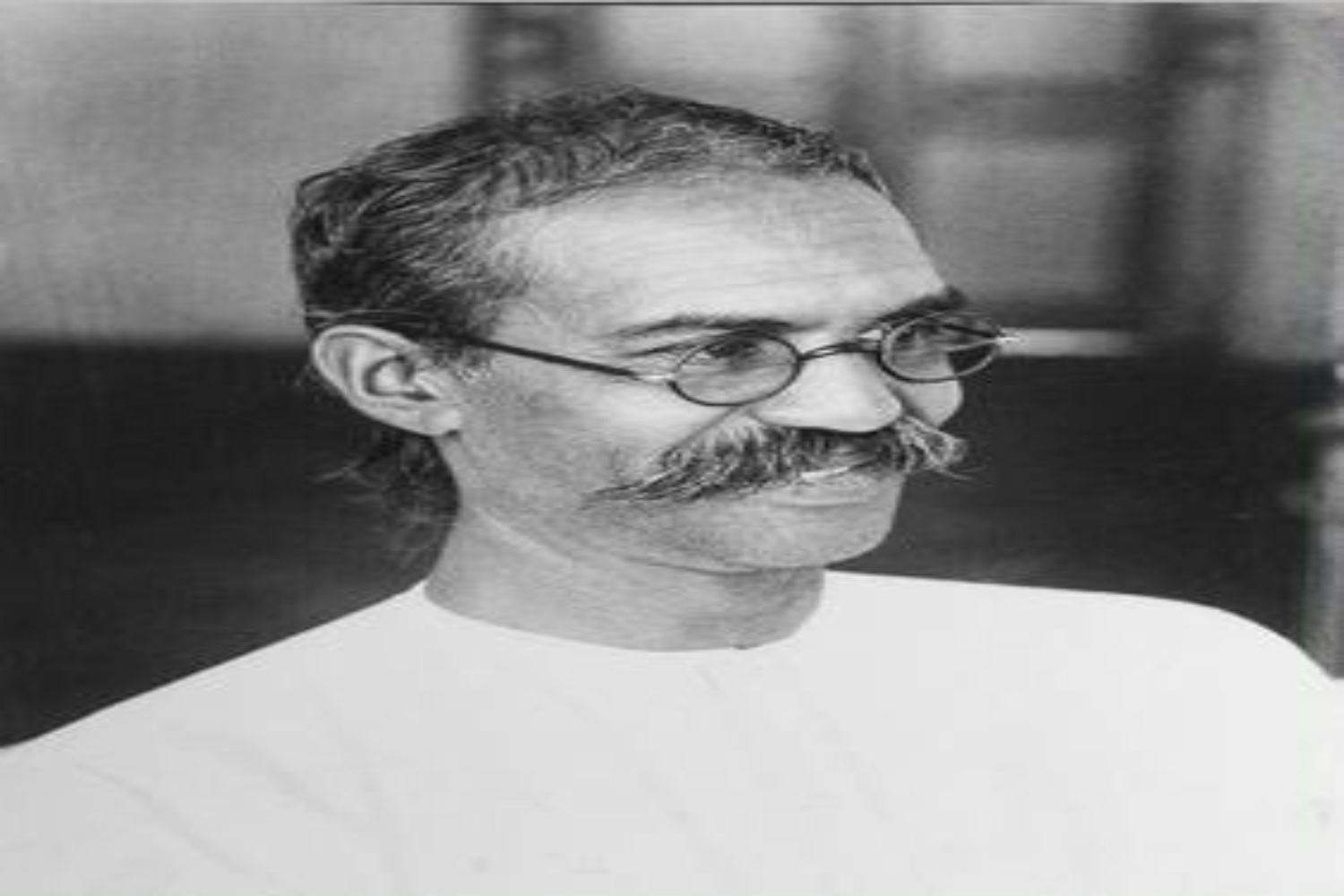

In this interview, Dr. Monimalika Day provides insights and guidance on inclusion in Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE).

Dr Monimalika Day (Ph.D. Special Education, University of Maryland) teaches in the School of Education Studies at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University, Delhi. She specializes in child development, early childhood education and special education. She has worked in NGOs and has taught in universities in India and the USA. She has partnered with UNICEF state offices and the World Bank to develop parenting programs and strengthen preschool education in various states in India. Her empirical research on early stimulation, quality of preschool education, inclusion of children with disabilities, teacher education, and collaboration between schools and families has been published in various journals and books.

Vikramshila: What is inclusion? What kind of challenges do ECCE programs encounter in promoting inclusion? What strategies can be implemented to overcome these challenges and ensure inclusive environments?

Dr Monimalika Day: According to the National Association for Education of Young Children and the Division for Exceptional Children in the US, inclusive education is built on three fundamental pillars: access, participation and systemic support. To achieve inclusive early childhood care and education (ECCE), it is essential that all the three pillars are addressed.

In various sectors, such as private, government, and NGOs, instances have been observed where children from marginalized castes attend ECCE centers, while the teachers themselves belong to dominant castes. I have heard stories where teachers do not allow certain children to touch them, and they are often made to sit at the back of the classroom. This type of social environment conveys a clear message to the children that they are not valued and that the classroom is not their rightful place.

When it comes to access, there are certain areas where we observe limited representation of certain groups in ECCE programs. For instance, during my visits to Anganwadis in West Bengal, I have never come across a child with a disability in the classroom. However, according to the World Health Organization’s report on disability, it is estimated that approximately 15% of the population in any given area has some form of disability. Moreover, in areas where concerns such as malnutrition and inadequate access to healthcare exist, the percentage of individuals with disabilities is likely to be even higher. Unfortunately, many young children with disabilities are unable to access ECCE services altogether.

Another significant aspect to consider is the participation of children within the ECCE programs. In certain cases, children from historically marginalized castes are not allowed to fully participate in various classroom activities, unlike their counterparts from dominant castes.

I witnessed an example during my visit to a village, where both an Anganwadi and a balwadi were present, representing two separate early childhood programs. As I engaged in conversations with the local community, I discovered that the Anganwadi was situated in an area predominantly inhabited by higher caste families. Consequently, the children attending that Anganwadi primarily belonged to those families.

However, an issue arose due to the meal program provided by the Anganwadi. There were concerns about allowing children from different castes to eat together. This situation highlights how existing systemic problems are being perpetuated. Without genuine efforts and specific initiatives to address the issue of inclusion, we risk perpetuating and institutionalizing the very problems we seek to overcome.

In discussing participation, let us consider a scenario where a child with a visual disability is enrolled in a high-end private school. The child is seated at the back of the classroom with a group of other children and lacks the necessary learning resources, such as braille materials. The predominant teaching methods rely heavily on the use of visual materials including smartboard. The child is thus unable to participate in most activities fully. The child’s parents have independently hired a special educator who provides additional tutoring at home. This situation creates a parallel system rather than fostering genuine inclusion.

When we examine participation, it is essential to evaluate whether the child is able to fully engage in all aspects of the educational environment. For example, we need to ensure that the child can participate in playground activities. It is not acceptable for other children to be playing football, while the child with a disability is left on the sidelines in a wheelchair. To address this issue, we must consider creating inclusive games and activities where all children can actively participate. By promoting inclusivity, we send the message that every child is capable and valued and belong to that community. When we exclude the child from the activity, we are limiting the child’s learning opportunities.

The third pillar is systemic support. Often the child or the child’s family is blamed for inclusion not working. It is said that the families are in denial about the child’s disability. However, it is crucial to recognize that families are not in denial about their child’s needs. In fact, they spend a significant amount of time with their child and possess valuable insights that professionals may not have. Their concerns often stem from the fear that once their child is labelled, the child may face discrimination. Therefore, it is essential that the process of diagnosis or labeling is connected to appropriate support services. Each child’s needs and strengths may vary. Therefore, there is a need to develop individualized education plans for every child.

In many instances, schools tend to focus on basic self-help tasks only, such as providing baths and clean clothes, which is very problematic. It is assumed that the child is not capable of engaging in academic activities, and is often prepared only for vocational training. This approach fails to value the diversity among learners and their unique abilities. Inclusion, when addressing disability or any other form of marginalization, is about valuing and respecting the diverse contributions of individuals within society.

Vikramshila: How can early childhood educators be trained to ensure that they are able to create an inclusive learning environment that promotes gender equality and social justice?

Dr Monimalika Day: There is a significant gap in training when it comes to inclusive education. In-service trainings, when they do occur, are often sporadic, and lack clear definitions and mentorship. Furthermore, collaborations between educators and specialists, such as physical or occupational therapists, is limited or non-existent in many settings. There needs to be systemic changes to foster collaboration.

Often, there is a separate resource room where children may receive additional assistance. However, even that support may be inconsistent. Most schools lack Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). They fail to provide individualized services based on proper assessment in a timely manner. This approach reflects a charity approach, rather than a comprehensive and systemic support.

However, having worked in the US, I have witnessed educators and special educators collaboratively plan and teach entire classes or specific components together. For instance, occupational therapists with expertise in fine motor skills can contribute to improving the writing abilities of kindergarten children. Through programs like ‘Mat Man,’ children engage with basic shapes of English alphabets, learning through play and creating different letters.

This approach benefits children diagnosed with disabilities. It also helps those who struggle with reading and writing difficulties. When professionals from various disciplines collaborate with the teachers, positive outcomes can be achieved. The Rehabilitation Council of India (RCI) and the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) need to work together to identify the criteria for preparing teachers to create inclusive classrooms.

Unfortunately, the current lack of synergy between requirements of the two agencies exemplifies the systemic support issues that need to be addressed. Even if a teacher is committed to creating an inclusive environment in their classroom, they often have to go above and beyond their duty. The time required for collaboration between the special educator and the regular teacher, for example, is rarely allocated. This leaves little time for lesson planning. These challenges underscore the systemic problems that hinder the effective implementation of inclusive education.

Vikramshila: How do you know that inclusion is being implemented? How can the community and parents be included in this discourse?

Dr Monimalika Day: When inclusion is happening, there is a sense of belongingness for the children and families. They feel “I’m respected. I’m appreciated for whoever I am.” To bring about meaningful change, it is essential to engage with local communities and understand their perspectives and challenges. External interventions that are short-lived and not sustained will not lead to significant transformation.

Instead, we need to identify the issues that local people perceive as problems and work collaboratively to address them. For instance, some balwadi programs have specifically introduced a snack time in their routine to address issues of caste discrimination from a young age. This simple initiative can be a ‘low hanging fruit’ that brings about meaningful change.

It is important to acknowledge that while there may be major issues that cannot be ignored, we must also start somewhere. Otherwise, we inadvertently contribute to the perpetuation of oppression. For instance, when discussing parenting aspirations, it is crucial to engage in conversations with parents and challenge gender stereotypes. By asking open-ended questions about their aspirations for their children, we can encourage them to think beyond traditional gender roles. Additionally, inviting professionals from diverse fields, such as lady police officers, nurses, and doctors, to speak with parents and children about their careers and experiences can broaden their horizons and challenge societal norms.

From an ecological perspective, it is evident that change cannot be confined to the classroom alone. We must strive to transform the entire context surrounding ECCE programs. By engaging in these small but meaningful discussions and initiatives, we can begin to reshape the attitudes, beliefs and aspirations of families and communities.

Vikramshila: Should gender and social inclusion be a separate component or cross-cutting theme in the ECCE curriculum? Additionally, what strategies and recommendations can you provide for designing a curriculum that addresses the specific needs of marginalized groups?

Dr Monimalika Day: Both gender and social inclusion should be incorporated into the ECCE curriculum. However, it is important to have focused activities as well. The overall curriculum must address the broader framework of inclusion and discussions around marginalization. The specific emphasis, however, may vary depending on the context. For example, in certain communities, gender may not be a significant issue, but socioeconomic class might be. Therefore, the curriculum should be adaptable to the needs of the community and the learners.

It is crucial to recognize that teachers themselves may have experienced various forms of oppression related to caste, class or gender. Considering this, it becomes essential to provide training and ongoing support that addresses these issues. For instance, some organizations like incorporated genderfocused training alongside curriculum development. This helps create a safe and inclusive learning environment for all women, including those who may have disabilities. Empowering teachers is an important step towards achieving effective gender and social inclusion in ECCE.

Unfortunately, the reality is that Anganwadi workers often face systemic challenges and are burdened with excessive work expectations without adequate compensation. This limits their ability to fully engage in implementing inclusive practices. Addressing these systemic issues requires a broader societal commitment to valuing and supporting the crucial work of Anganwadi workers.

In terms of strategies and activities, it is beneficial to align the curriculum with specific learning goals for children with disabilities. This can be achieved by identifying the competencies associated with each activity and determining how a child with a disability can benefit from it. By integrating special education and general curriculum, the activity remains inclusive while focusing on the individual learning needs of the child. Existing frameworks can provide guidance in this regard.

I remember speaking to a woman who had a disability. She shared her experiences with me. When she attended her first training in Almora in Uttarakhand, she had never stepped out of her house before. She told me that during the 10-day program, she stayed upstairs for the first 7 days, because she was so afraid to join the training. It was a significant step for her.

During my time there, as I collected data for my research, she approached me and asked what I would give in return for the information she shared. Her question highlighted her journey of empowerment. It was a powerful moment that reminded me of the importance of fostering an inclusive and supportive environment for individuals like her.

Vikramshila: How can we incorporate activities and design resources that promote inclusion in the ECCE curriculum? Are there any specific recommendations you would like to share for practitioners, educators and organizations?

Dr Monimalika Day: In many schools, there is a requirement for implementing a system called Response to Intervention (RTI). This approach brings about systemic change by conducting screenings to identify students who may be struggling academically. Based on the results, interventions are designed to provide support to both high-achieving students and those who need additional assistance. Small group work is emphasized to ensure that all children, regardless of their performance level, have opportunities for engagement.

Ideally, a curriculum should include activities for large groups, small groups, and individual work. However, we often observe that even in high-end schools, there is a heavy emphasis on large group activities, with minimal small group or individualized attention. Consequently, some children who are unable to keep up with the pace may fall behind. Prof. Mohanty from JNU often reminded us that there are only “push outs not drop outs.”

It is essential to shift our focus from solely identifying children’s problems to recognizing their strengths and talents. Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) should be developed to address deficits and nurture and enhance children’s strengths. By acknowledging and nurturing the strengths of each child, we contribute to their holistic development. For instance, if we view someone like Stephen Hawking merely as a person with physical disabilities, we fail to recognize the immense intellectual contributions he made to the world. It is a huge loss for the society when we overlook the strengths and potential of individuals.

Moreover, the need for inclusivity extends beyond disabilities and encompasses other aspects such as gender and race. It is crucial to provide diverse materials and resources that reflect the various facial features, complexions, and backgrounds of children. This includes dolls and other play materials that represent the diverse population. It may be challenging to find commercially available products that address every local context. However, we can explore creating standard kits and providing guidance to local communities to develop materials that align with their specific needs and the diversity in their community.

Procuring materials solely from the mainstream market limits our options and reinforces dominant narratives. We need to challenge and reshape these market norms by actively involving designers who can cater to the unique requirements of inclusive education. By collaborating with experts in design, we can create materials that better serve the diverse needs of children. This will also help in breaking free from the limitations of what is commonly available in the market.

Furthermore, institutions like Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) have significant influence due to their large scale and reach. They can play a role in guiding the market by clearly communicating their design requirements and engaging designers who can create materials that align with the principles of inclusivity. We need to leverage the expertise of designers and incorporate the specific needs of diverse learners. By doing this, we can ensure that educational materials and resources are inclusive and representative of all children.

Vikramshila: In your opinion, what role can policymakers and government agencies play in promoting gender and social inclusion in ECCE programs?

Dr Monimalika Day: Convergence between different policies in the Indian context is lacking, especially at the policy level. It is crucial for the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), the Department of Education and the Health Department to work together when addressing the needs of children with disabilities. In the United States, they have implemented an Inter-Agency Coordinating Council. There representatives from various departments collaborate and ensure their alignment with decision-making processes.

It is essential to have such coordination and convergence in India as well. For instance, when considering changes like the colocation of the Anganwadi or the focus on foundational learning, it is important to determine if the MWCD is on board with the Department of Education’s initiatives. Strengthening these convergences and establishing committees or councils on the ground can be helpful in monitoring and facilitating necessary changes.

Additionally, collecting relevant data is crucial for effective monitoring and evaluation. It is important to track indicators such as the enrolment and graduation rates of children with disabilities and children from marginalized backgrounds. Without monitoring, these issues can easily go unnoticed. These then result in lack of appropriate interventions and support. Therefore, data collection should go beyond mere access to education and consider broader outcomes.

In terms of promoting inclusive education, many organizations have focused on specific issues like disabilities or gender. However, there is still a need for a comprehensive framework that defines and translates inclusion on the ground. While the Persons with Disabilities (PWD) Act does provide a definition of inclusion, its practical implementation requires more clarity.

Principles of Universal Designs have been used to develop Universal Designs for Learning. In developing a curriculum, it is crucial to involve special educators from the beginning. This can ensure that their expertise informs the process effectively.

A participatory process is essential. One way to achieve it is by involving persons with disabilities in these initiatives. They bring valuable experiential knowledge from their own educational journeys, even if they may not be well-versed in research. Their perspectives can contribute to the focus and direction of committees or working groups. This can be especially useful when it comes to addressing issues faced by marginalized communities.

The curriculum development work in West Bengal serves as an excellent example. It has had representatives from CDPOs, DPOs, supervisors, and other relevant stakeholders. The inclusion of all necessary voices in the participatory process ensures greater acceptance and relevance of the developed curriculum. The fact that it was created in the local language, Bengali, and later translated, further reinforces its importance and effectiveness.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!